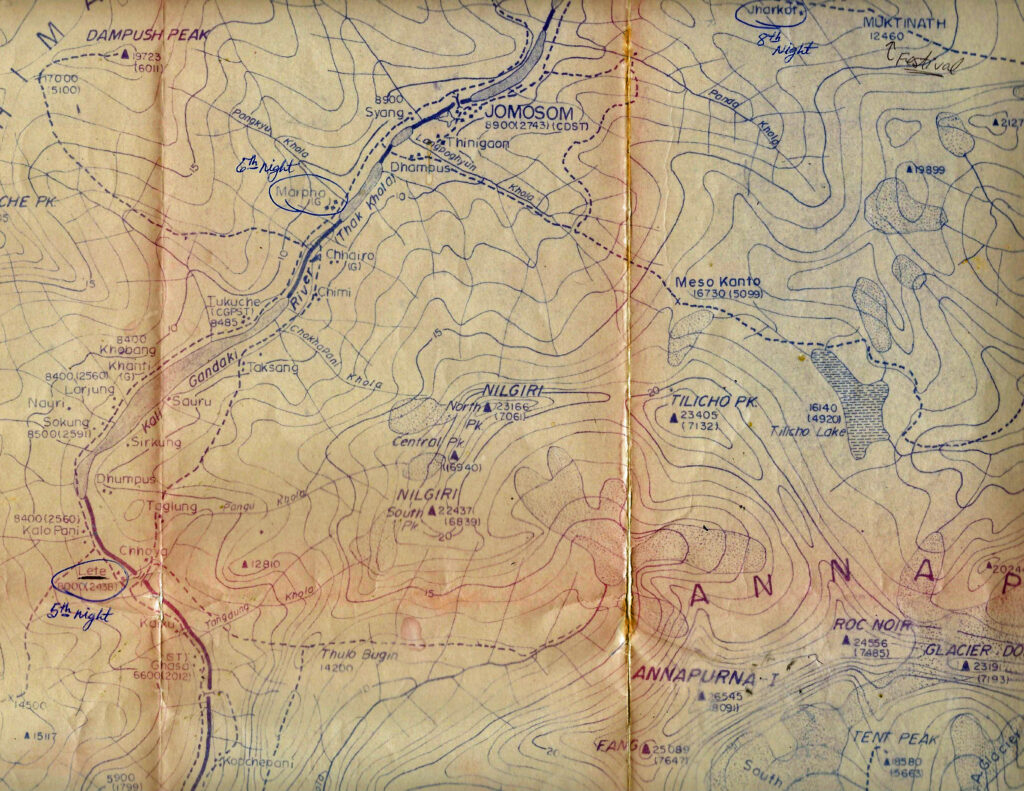

After a breakfast of singed nan and gritty porridge prepared by our Lete innkeeper, Marianique and I left our primeval yak-pen lodging under a clear sky and headed northward up the Kali Gandaki River Valley—forgetting, of course, to re-cross the swaying bridge back to the main trail from which we had come the evening before. We wholly spaced the re-crossing, being far more intent on pushing upward into the mountains. In any case, our map showed trails on both sides of the valley. That was a mistake.

As we walked, the forests dwindled to scrubby thickets and the scenery became more grassy-alpine and windswept. The river broadened into a broad sluice of rippling glacial melt through expansive beds of gravel, unlike the roaring cataracts we had looked down upon the previous day. Our trail became gravelly, widened to nearly indistinguishable, and forked every half mile without apparent signage.

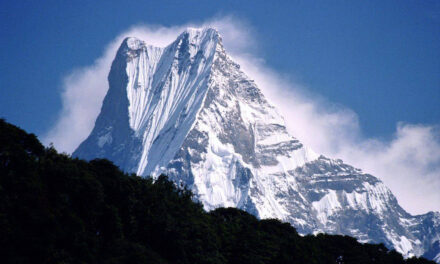

Dhaulagiri rose through clouds to the west and the Nilgiris to the immediate east, with the tops of three Annapurnas poking above, all far above 20,000 feet. We plodded slowly up the valley at an elevation higher than any peaks in California’s Tahoe basin, between mountains that were still 10-15,000 feet higher than us. Per Geological field trips in the Himalaya, Karakoram and Tibet (2014), this valley forms the deepest gorge in the world. As I tripped along, trying to ogle upward and hike simultaneously, my neck developed a chronic kink from craning around my backpack frame.

We were soon plagued by chilly headwinds and dust clouds from the north that intermittently rolled down the valley from Tibet and enveloped us like little haboobs. When the winds hit, we turned our backs, closed our eyes, and waited for the worst of them to pass. My saliva turned brown and pasty, and I worried about chipping my teeth on the abrasive grit when I ate my meager trail snacks.

Later that afternoon, Marianique and I realized we were on the wrong path, thanks to our barging northward that morning without thoroughly studying the map. We noticed the problem when we spied our destination village on the opposite side of the broad valley and on the other side of the rushing waters that we paralleled. We’d expected there would eventually be a bridge to lead us across, but there was nothing—no crossing—anywhere. Unless we wanted to retrace the entire morning’s trudge, a river fording was in order. We kept hiking—hoping for a bridge but starting to look for shallows.

Finding no bridge, we eventually located a spot where the river looked less deep, where the water appeared no more than waist level. Yet the surface rippled in the telltale way of swift waters. It was hard to judge. We looked at each other, knowing we had to commit to a crossing or keep walking. But we couldn’t just keep walking because the river eventually hugged the steep eastern flanks of the Nilgiris. There we would be stuck. One thing we both knew, despite our inability to communicate: we were not walking back all the way back to Lete.

I dropped my pack and stared into the moving waters. We would have to strip to our underwear or hike the rest of the day in wet pants in the cold, blowing dust. I looked at Marianique. She looked perplexed. I sat down on the gravel and began untying my shoes. When I looked up, my hiking partner was in her underwear, barefoot, and hoisting her pack. Somewhat embarrassed, I followed suit.

We both waded in. The water was so frigid that it made me gasp. The gravelly course was deeper than it had appeared and I was immediately up to my hips and barely a third of the way across. My lower extremities were so cold that they immediately went numb, so if I stepped on a sharp rock I might feel nothing. Not a good scenario. As I paused, the current lifted me slightly and moved me a little downstream. I teetered under my pack’s weight. We both stopped pushing across and turned around, simultaneously seeing the potential folly in continuing.

Had we fallen in, we might still have still made it across, but we and our gear would have been soaked. The cataracts were now miles downstream, so there was no danger of going over a waterfall. The real threat was hypothermia. The air temperature was still in the 40s so the only way a soaked body might warm up was to keep hiking. We might dry the gear out if the sun stayed free of clouds, but once evening set in our wet things would freeze solid. Putting our dry clothes back on again, we continued upstream.

Twenty minutes later, we retried crossing the icy waters again. Same protocol. Again, we retreated, re-clothed, and walked further upstream.

Finally, more than an hour after the first endeavor, we spotted a wider point in the river and tried again. We slowly crept across through waist-deep rapids, stumbling and swearing, pushing and floundering, until we had fully crossed. Once on the other side, elated at not having perished in the cold torrent, not yet warm enough to have feeling in our lower extremities, the sky then let loose and icy rains fell upon us.

“What the…?” I asked aloud. Early monsoon, I thought.

Marianique agitatedly muttered something in French that I didn’t understand. But I felt the same way. We reclothed in the rain.

As we trudged onward across the valley, aiming for the trail on the west side, the dusty winds coated our wet clothes and sweaty faces with a layer of silt. We were frigid, filthy messes.

*

Far across the windswept Kali Gandaki Valley we finally reached the village of Marpha, positioned below an old monastery that clung to the base of rocky cliffs. Children with outstretched hands ran to us as we entered the town yelling, “Chocolate!”, but of course we had no chocolate—only weary smiles. Boulders perched above the town were painted with orange and white triangles, Buddhist ornamentation seemingly from some ancient time. Everywhere prayer flags flapped in the wind. Surrounded by thousands of rocky vertical feet, I wondered if there’d be any warning before a landslide, or serac, fell from above and crushed us where we stood.

That evening, I climbed up to the rock paintings. On the river plane below were dry rice paddies that must have flourished during the wet months. The milky-blue river we forded rippled north and south between the peaks to vanishing points in both directions. Above was a dark sapphire sky, bare of jet trails, cleared of clouds, and ready for the oncoming brutal chill of nighttime. Directly in front of me loomed the Nilgiris: vertical cliffs, icy and mean. White wind-driven ice plumes sprouted from their knife-edge tops. Every hour or so, avalanches and rocks roared down their flanks, which you often missed seeing but heard in reverberating echoes. The mountains looked lonely, cold, and cruel. Not a place for humans. Yet, people climbed up there.

The night in Marpha was arctic. Frozen gusts swept down the valley and whistled through every hole and cleft in the rock-walled tea house where we spent the night. A dinner of lintels and small potatoes was served in the light of a Coleman lantern under a corrugated metal roof. There were only a handful of trekkers, and we wore every scrap of clothing we brought. Capped, hooded, and zipped up, we all shivered together at the communal table.

One remarkable thing that Marpha offered, besides its old monastery and orange-adorned rocks, was apple pie. Someone, somewhere up there, grew apples and knew how to make pies! Our innkeeper eagerly sold slices to the clientele. I had two slices.

*

With pie re-filled bellies, Marianique and I set off northward the following day, seeing far more Tibetan-looking types wandering the trail. Some were alone. Others walked in the company of yaks or mule caravans. They dressed in reds and ochres and wore braided hair, beads, and ribbons. Their androgynous appearance made it hard to tell men from women. As we passed on the trail, some begged from us with open hands—and always with beaming smiles even if they were given nothing.

Stunted remnants of the Nepalese forests were now lost to desert-like sages and grasses. We hiked leaning forward, pushing into a constant headwind. As we eked our way through the Kali Gandaki gorge, the landscape took on the arid appearance of Nevada. In a dreamlike trance, Marianique and I pounded out mile after mile, fording our way back and forth through the icy river—which had thankfully grown broader and less deep as we crossed through the mountains.

At Jomsom, the trail’s namesake, there were a few simple buildings, a dirt landing strip scratched into the valley floor, and the terminus of the most decrepit telephone line I had ever seen. We bought chi inside a rock hut and watched the afternoon winds blow dust around us while local vendors hawked their wool handicrafts to a radio blaring the sound of Nepalese children practicing English in unison.

Hours later, at Kagbeni, our trail veered up from the Kali Gandaki Valley floor toward Muktinath, splitting off from the route that went on to Mustang. The Mustang district was the last bastion of unyoked Tibet culture following the invasion of China in the 1950s, and still off limits to western travelers. I was now on the edge of that great Tibetan plateau I had always heard about. The massive peaks we had walked between the previous day were now south of us and receding into the distances.

*

Kagbeni looked and felt medieval. It had no power, sanitation, running water, roads, shade trees, or other features of modern civilization. It was a gateway village between Nepal’s populous, irrigated parts and the dry expanse to the north, between the trekking zone and the protected Tibetan villages just south of China’s grasp. It seemed like one of those relic places that was built and rebuilt upon its own ruins for a thousand years.

We stayed at the Red House Lodge, one of the few trekker inns in the village. This “lodge” was a dilapidated, cliffside, red adobe cavern in the midst of Kagbeni’s disheveled center. To reach the place, we passed through dark alleys, slipped through an unshoveled horse stall, and then climbed a primitive ladder that looked like something from a Pueblo Indian Museum. The accommodation was at the end of a labyrinth of dark, second-story passageways. Despite its modest appearance, its position above the surrounding buildings provided fantastic views down to the river wash and southward toward the peaks from which we’d come.

The Tibetan influence was strong in Kagbeni. The inhabitants–male and female–wore their long dark tresses tied up with ribbons, and dressed in thick, colorful red and burgundy robes. That was Tibetan androgyny. Despite their poverty, the locals were gregarious, good-natured, and always smiled.

There was something refreshing about entering Kagbeni and making our way to the Red House Inn—we had finally shed civilization’s grip. It had taken Marianique and me a full week to get there, with no roads in and now no way to communicate out. I looked forward to hearing about the poignant experiences of my fellow travelers.

*

Evening at the Red House Lodge found some ten people seated around a dingy, wood-hewn table in a dark room lit by only a candle or two—weary trekkers teetered on wobbly benches on an uneven plank floor. An old, robed woman served us rice and Dahl, the Himalayan staple, for a few rupees each. Since we were far beyond any forests, there was no wood and therefore no fire for warmth, so the cold crept in, working its way first into feet and knees, then calves and thighs. After the simple meal, everyone sat back, shivered, and shared stories.

The conversation drifted from generic travel tales to curious exploits, worst accommodations, strangest foods, and the most denigrating bouts of sickness. Some of the stories made me cringe. We were from across the world, each of us seemingly instilled with a sense of modesty about our respective journeys, openness as to each other’s viewpoints, and respect for the places we’d found ourselves, however odd or threatening those places turned out to be. Except for one American girl, who seemed more bent on loudly vocalizing about her familiarity with Pacific beaches, her “bitchin” club hopping in Los Angeles, and vague references to her “excellent” California party experiences. She wouldn’t stop talking. The other travelers were all too polite and exhausted to tell her to “kindly lower your voice and shut the hell up.”

As the girl rambled on and on, a rather grimy traveler who had been listening quietly from the corner of the room rose from his chair. With long brown hair, a tattered Euro-style scarf, and still in his hiking boots, he looked to have been on the road for a very long time. He smiled, but his eyes indicated that he held the girl in contempt. As if on cue, he chimed in with an experience of drinking an alcoholic elixir made of Yak milk, then rolled into a story about smoking hashish on a hotel rooftop in Cairo. I recognized his accent. Like me, he was a Californian.

That conversational twist brought the group, with his guidance, to the tepid topic of intoxicants. Everyone had a favorite drunken or drug-induced tale, many having occurred covertly and illegally in foreign countries. That topic infused energy into the freezing room. The girl listened wide eyed, mumbling “grody!” a time or two.

Now seated at the table with the others, the trekker coaxed a story from each traveler who could speak English—the Germans, the French couple, the Brits, and even the Thai guy. It was a group deposition of sorts. Finally, not to be outdone, and leaning in toward the flickering candle with a raised voice, the girl abruptly cut in and offered up a rather long-winded and sophomoric pot-smoking experience that occurred on a Mexican beach. She giggled at herself and threw out So Cal names and terms that only an American might know. She blathered on with the air of a Malibu princess fresh off the jet from Los Angeles.

The scarved trekker-turned deposer sat opposite the girl and smiled at her until she was fully finished. She was beaming—almost gloatingly. He stared into her as if analyzing her intentions. I wondered about those too, and if she was still in her teens.

“Nice to meet you!” he finally said. “I’m Doug.”

She smiled back.

“So, where are you from?” he asked.

“Like, El-lay,” she responded, giving him the side-eye.

“Ah, Los Angeles. Cool! Were you born there?”

“Fer shurrr,” she replied.

“Where did you go to high school?” he persisted.

She paused, then quietly said, “Northridge.”

“A Valley Girl!” Doug exclaimed with a smile.

I could sense Doug’s brain working, churning—his disdain for the girl growing. He didn’t like her and was working her, heading in a direction to address her airs and to pull back the Malibu curtain that cloaked a girl from The Valley. But she didn’t sense it.

Doug then shifted the group conversation to the topic of psychedelic drugs—adding how they could enhance an experience if one could stay “cool” in the face of a shifting reality. Several of the group agreed with that notion and piped up, offering amusing examples reflecting their personal drug experiences and stamina. Not to be outdone—and predictably—the girl then blurted out how she could hold her own with any psychotropic substance—adding that the best came from California.

“Oh. Sounds like you might want to party?” responded her scarved inquisitor.

“Totally!” she responded, with an air of confidence indifference.

Then, with a smirk, Doug reached into his coat pocket and produced a golf ball-sized black lump, which he rolled across the table toward the girl. “Here’s some weak stuff from Kathmandu for you to try.” Then he added, “This won’t be anything like what you’ve got in LA.”

The ball came to rest in front of the girl. All eyes around the table widened, following the tarry blob’s trajectory. It was hashish. A lot of it.

“You might need this, too,” he added, pulling a little carved dugout pipe and lighter from his other pocket. He held them up in the meager light.

At that point, Marianique rose from the table and left the group in visible disgust.

The girl smiled and boldly picked up the black ball. She tossed it up in the air and then caught it, as if demonstrating some hand-eye aptitude for weights and measures.

“This is hashish?” she queried out loud to the group. That was followed quickly by, “Er, what-ever!” as if to waive off any air of trepidation.

Oh God, I thought. This should be amusing.

Doug walked over to her, carved off a big chip with a pocketknife, and nimbly filled the pipe. She lit it, took a hit and the hash sizzled. White smoke curled upward into her blonde hair. The girl choked out the hit, took another one, and choked again as if conspicuously standing firm in the face of a challenge. The pipe then went around the table, and most everyone partook. Soon chatter was replaced with coughing and uncontrolled bouts of laughter. She, of course, was the loudest.

Each time the pipe returned to him, Doug systematically reloaded, re-lit, and then passed it around again. He playfully chide the girl for being a lightweight, and she kept taking the pipe. It was a déjà vu of my college days in the dorms. Doug was relentless and his teeth slowly blackened from the tarry vapors.

One by one, faltering participants got up and staggered away into the darkness. There was enough secondhand smoke in the room to pulverize even the nonparticipants. The Valley Girl finally grew less chatty, then mumbled, “Oh my Gawd!” and went silent. Then her eyes rolled upward as she succumbed to her limitations, and she passed out—slowly slumping sideways out of her chair onto the wood floor and landing with a thud. She partly recovered consciousness with some canteen water splashed onto her clammy face, whereupon a French couple helped her stagger off to her room. They were not amused.

Doug seemed oddly pleased. The girl—a stereotypical Yankee embarrassment to both of us—had been silenced. As I watched the scene unfold, I felt like I had witnessed a medieval inquisition: if she sinks, she’s a witch. The girl sank.

The Germans weren’t pleased either and shook disapproving heads as they left the table. And what about Marianique, I wondered—whom I would see in the morning? Would she blame me for letting this happen? Well, she couldn’t vocalize her disapproval to me in English, so it didn’t really matter what she thought. In partial defense of what occurred, I reasoned that no one ever died from smoking cannabis—whatever its form.

In the end, only the girl’s tormentor and I were left at the table. We mused together for some time, reminiscing about our adventures at home and abroad. He seemed oddly familiar, as if I’d run into a ghost from my past. Had he really introduced himself as Doug? My mind tried to put a finger on where we might have met. His red-streaked eyes strobed into me, bringing back memories of my own demented misbehaviors. Still, I couldn’t specifically recall his face.

Ultimately, I commended the grimy traveler for his fine choice of victims, thanked him for the vapors, and stumbled off to my own bed. As I drifted off into fitful dreams of apple pies, androgynous Tibetans, and icy places, I chuckled over the slap-down of the cocky Californian—even if she was one of our own—and guiltily wondered if the girl’s trial and punishment somehow demeaned the purity and sanctity of this Himalayan wonderland.

How bizarre to read about a trek I was on forty years ago, on the same dates, on the same route, knowing that. as this narrative continues, I am going to cross paths with the author. It’s not as though I feel like I was there — I WAS there! Life is too weird! (For the record, I’m glad I missed the scene at the table, and I’m glad that Beverly and I never had to ford any rivers — I was a lightweight then, and a lightweight still. But you, sir, You the Man! 😉 Thanks for this