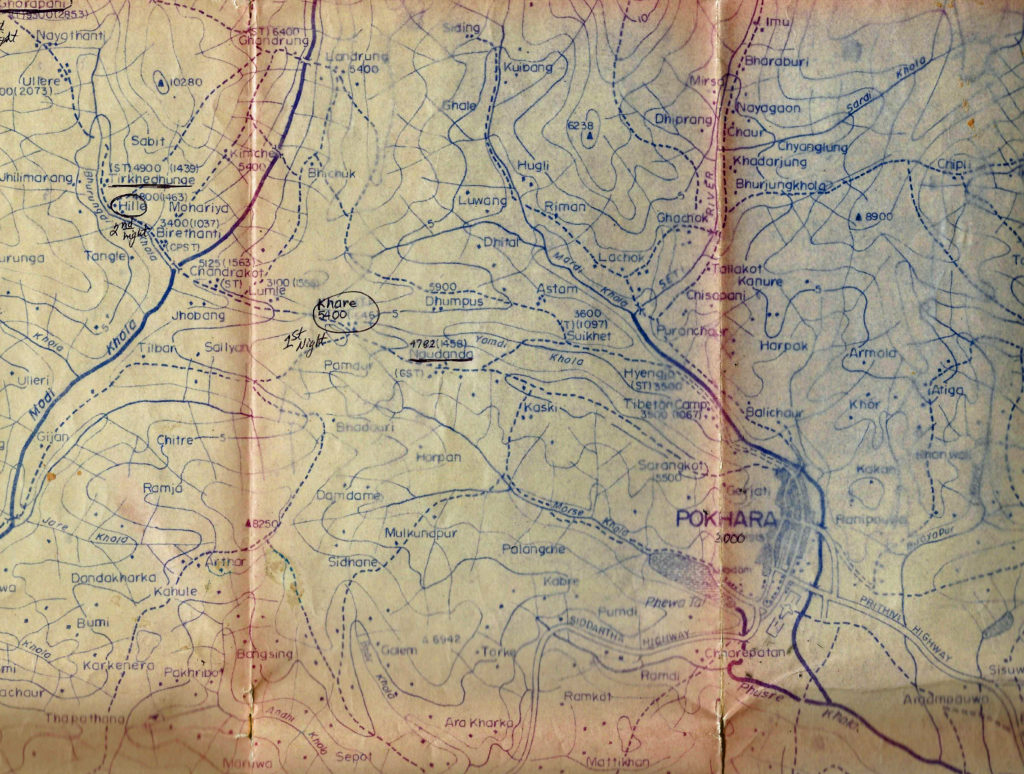

Near the top of the ridge above Pokhara, I came to a fork in the trail. It was poorly marked so I dropped my pack and dug the map out its pocket for a quick review of my location. Would the entire trek be like this? Referring to the map’s topographical features, I found the intersection. It was another trail from Pokhara joining mine. Reassured that I wasn’t lost, I slipped the map back into its pocket.

Then I continued to stew about not having a trekking mate; guessing that my streak of supernormal luck had ended. All those wished and willed occurrences were only a reflection of coincidences—just crap. My stomach began tying itself into a knot.

As I stood wiping the sweat off my face, staring at the mountains, and slogging down some water from my large canteen, I heard “allo!” and ”excusez” from behind me. I swung around.

A girl had sauntered up the trail when I wasn’t looking, appearing out of nowhere. She was alone. She approached me and asked for directions—but not in English. When I tried to communicate back, she understood nothing I said. She apparently spoke no English. In an attempt to be helpful, I pulled out my map again and we just pointed at things. She did communicate that her name was Marianique and that she was from “Français.” Her finger indicated that she was taking the same route as me. But that was the best she could do. Damn, I thought.

“No Anglais?” I asked?

She shook her head to indicate, “No English. Not a bit.”

“Habla Espanol?” I could manage that if she could.

She shook her head again.

“Sprechen sie Deutsch?” I knew far more German words than French, having put my mind to that for a month in Europe, especially having stayed with a non-English speaking Nurnberg family for the better part of a week.

She again shook her head. Now I was shaking mine. The girl could only speak her native tongue and looked more alone than I felt. She didn’t even have a decent map.

It was odd that Marianique didn’t speak a little Spanish. That might have helped us bridge the linguistic chasm. After all, Spain was her next-door neighbor. Yet I knew plenty of Californians who didn’t know a lick of Spanish—but for the words “Cerveza”, and “si”, and “por favor.” That was true for most Americans, even those who lived near our southern borders. Such an indifferent attitude toward the world seemed arrogant in a way. Guess the French could be as clueless as us. Damn! Here we were, two eager communicators under a lingual cone of silence.

Marianique and I took nonverbal stock of each other as we stood on the trail. I sized up her pack, her boots, and her demeanor. I guess she sized me up, as well. Clearly we each needed a partner. But that need couldn’t even be vocalized. Despite my frustration with the language gap, I saw courage and mental fortitude in her. I felt it. So this was it? The miracle I had tried to will? Someone I couldn’t even talk to? How bizarre.

We stood in silence for a few more awkward moments, then I said her name and made the following gestures: first I pointed at her, then I pointed at myself, and then I pointed up the trail and made the walking-man motion with the fingers of that same hand. She looked at me and smiled. She got the point. We didn’t require vocalization, because we understood. We both accepted the concept of pairing up—at least until we didn’t want to anymore.

Thus we set off up the trail: total strangers. I would later learn that Marianique was from Paris. It seemed ironic that my total lack of French fluency had been turned right back in my face. What French girl didn’t speak English in 1982? Well, what world traveler didn’t speak a bit of French? It cut both ways.

On the positive side, Marianique was scrappy, aloof, and not one who might pull my romantic strings. She was an incarnation of Peppermint Patty from the Peanuts comic strip—without the glasses. That was fine by me. Plus, she hiked like a demon. That seemed uncanny. Our combined states of aloneness drew us together like long-lost siblings; brother and sister. She eventually indicated on my map that she wanted to go all the way to Muktinath—my own destination. Marianique was cheerful and had a goal. I’d found my trekking mate.

Since we couldn’t converse with each other, our direct communication was more by physical actions than through words. We mimed. We pointed. In a way, we appeared like one of those older married couples who could be together silently because they’d run out of new things to say. We had things to say but just lacked the common vocabulary.

I had no idea that Marianique would push me like a drill sergeant for eighteen days, causing me blisters, exhaustion, and challenging my male hiking prowess. Only later in the trek did a fellow traveler translate to me that she was a psychiatric nurse. So I had my own personal trainer and shrink–albeit one who couldn’t give me any advice. Together we played a game of charades through the Himalayas. I owe my trekking accomplishment to her determination.

*

The Himalayan trails above Pokhara were dotted with little villages that took in travelers. What I had heard was true: for a few US dollars per night, we were fed stews and teas, given sparse sleeping quarters, and fed breakfast the following day, all to the amusement of runny-nosed children who hung around laughing and watching us eat and talk.

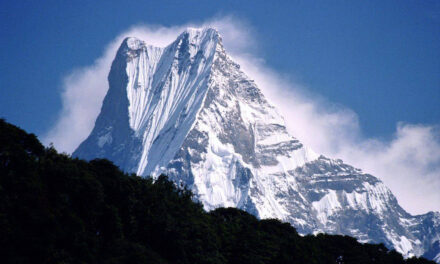

Using the map, Marianique and I nonverbally agreed that Naudanda would be a good goal for the first night. It was a village 2,500 feet above the trailhead, a good day’s slog in the heat. By late afternoon we had reached our destination—the first substantial settlement on the trek—and we stopped for chai. It was a delightful place, still below the forests but with views of Machapuchare in the distance.

By then, I was done; ready to take my shoes off and put my feet up. But Marinaique wanted to keep up the pace. So we finished our refreshments and pushed on to Kanre, a smaller village at the northern part of the ridge we were negotiating above Pokhara.

In Kanre I got my first taste of trekking accommodations.

Our hosts were gracious, cheerful, and service-oriented, even in the face of their country’s onslaught by foreign hikers—which had been going on for years. Our accommodation was a wooden structure, mostly bamboo, partly perched upon stilts on a hillside. Marianique and I dropped our packs into separate rooms and the innkeeper took our requests for dinner. It was a delightful trailside inn and tea house with expansive views; delightful until I was beset with chattering, laughing, singing, pounding, and breakfast-making noise well before dawn the next morning.

God knows why the Nepalese villagers arose and started the day so early, but it was their way. They awoke long before the sun. Moreover, crowing roosters and barking dogs lived under our sleeping quarters and commenced their own ruckus as soon as the local birds began chattering. That was earlier than the Nepalese—before first light. The entire night was full of sounds: children laughing and crying, chickens clucking, pigs snorting, and dogs whining. People and animals lived in close proximity, and the bamboo mat walls didn’t muffle anything. I needed earplugs.

*

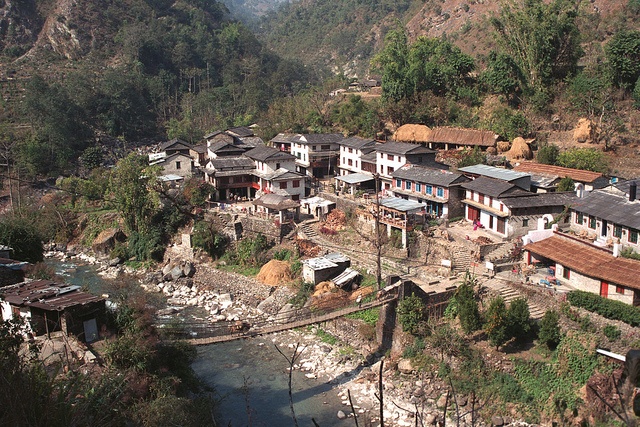

The next day our trail dropped a couple of thousand feet to cross the Modi Khola River at the village of Birethanti. A suspended bridge took us over moving water that a fellow traveler described as full of leeches. I apprehensively looked beneath the jiggling bridge as we crossed. Below the bridge was a vast thicket of marijuana.

It was Birethanti where I discovered that my smarting feet were already sprouting blisters beneath blisters. That wasn’t good. I’d bought a second-hand pair of leather hiking boots in Kathmandu similar to mine at home but, they apparently didn’t like me. Armed with my recent tetanus shot, I considered hiking in flip-flops. But there was horse and mule dung on the trail. I envisioned stepping into a fresh pile of horse crap in sweaty flip-flops. Instead, I slipped on my neon blue Saucony running shoes that I’d packed as my after-hiking footwear. Now I was a luminous trekker. Thereafter, I was continuously pestered by Nepalese men offering to buy my colorful shoes.

The river at Birethanti was surrounded by rice paddies, banana trees, giant bamboo, and, as we had seen, wild marijuana plants. We didn’t stop. As we continued upward, stock trains passed us coming out of the mountains. They carried rice up to the higher elevations and returned with bulky loads of yak wool. Ever upward, we coursed over an undulating landscape.

We forded cascading streams with blue-green pools and crossed larger torrents on log balance beams or on wood-planked suspension bridges. The crossings were often precarious. Always, we moved aside for animal trains coming down the trail. Mules wore fashionable headdresses and tail decorations with bells that warned of their approach.

The second night—still hiking together—Marinaique and I stopped for a stay at the Hille Tea House right alongside the Jomsom Trail. It was just us and a group of four Germans. Again, we were provided rooms and meals for a very bargain price. The inn’s blue porch looked out over the village of Hille and across the valley at the rhododendron forests. Mule trains plodded by, clomping and clanging on the stone path as we feasted on a stew of chicken, lintels, and little yellow potatoes with naan.

Following dinner, the Germans ordered a local brew made from Yak milk and then commenced smoking a bit of marijuana. As I watched, they complained about the weed among themselves in German, which I didn’t understand but which was easy enough to interpret. The rolled herb was making them wheeze and wasn’t having the desired effects. One of them looked over at me and said, “dies grass is sheeet.”

I liked Germans and had occasionally traveled with them during my wanderings, finding the younger generation to be educated, mutli-lingual, and rather open-minded. I smiled, motioned “one minute” with a raised finger, and left the porch to visit my backpack. A few minutes later I returned with a golfball-sized blob of Nepalese hashish that I had purchased in a back alley in Kathmandu—my sleep aid, attitude adjuster, and higher offering for international peace. I revealed it to them in its gooey black glory. Wide-eyed, they invited me to their table where I plopped it down with my little stone hash pipe from Pokhara.

The Germans didn’t mind choking on the vaporous toxins of my resinous elixir. In the course of the next half hour, I was incorporated into their group as some exalted mountain wizard. Soon our group was sharing travel stories and making social and political commentary like old friends.

Later, we all took a walk down a narrow trail below the village, meandering between rice terraces, to the edge of a great cliff overlooking the river gorge. Everything dropped away precipitously below us. We stood before the spectacle in silent awe, witnessing the evening jungle sounds slowly becoming as loud as the roaring waters below.

*

On the third day, Marinaique arose at dawn, ate, and indicated that she wanted to get right back to hiking. I sensed that she was suddenly aloof; perhaps put off by my not-so-pure-and-sweet activities with the Germans the evening before. She hadn’t joined in with us. I obliged, yet realized that I was traveling with someone with the same preconceived expectations that had vexed me as I had looked for a trek mate several days before. Ugh! I lamented. I resolved that her expectations would not be my problem.

We hiked up thousands of feet through thick rhododendron forests. It was bloom season and entire mountainsides were covered with flowering canopies of red, purple, and pink. Each tree was a separate brushstroke of color: but not hues one would expect to see in the forest. These were colors from some stoned artist gone silly with hallucinogenic paints. The patchwork of color was set upon a background of jungle green. Tree branches were draped with mosses and bromeliads. Monkeys yammered down from the canopy. Above it all were the snowy crags of the peaks we approached.

The trail turned into a path of hand-made pavers between the buildings of villages we passed through, presumably to reduce the mud and to provide cleanable surfaces. Runny-nosed children scurried out of doorways and followed us, begging for chocolate with outreached hands. None cursed us or cried when handouts weren’t forthcoming. We usually responded to their requests with a smile and a “Namaste!”

As we rose higher, the people looked more and more like the Tibetan neighbors to the north. Prayer wheels adorned the trailside in the larger villages. Travelers reached out and spun them as they passed by.

Mesmerized, I stumbled along the often precipitous path, not wanting to remove my eyes from the sights around me, hardly willing to attend to the mundane responsibility of keeping visual track of my own feet.

*

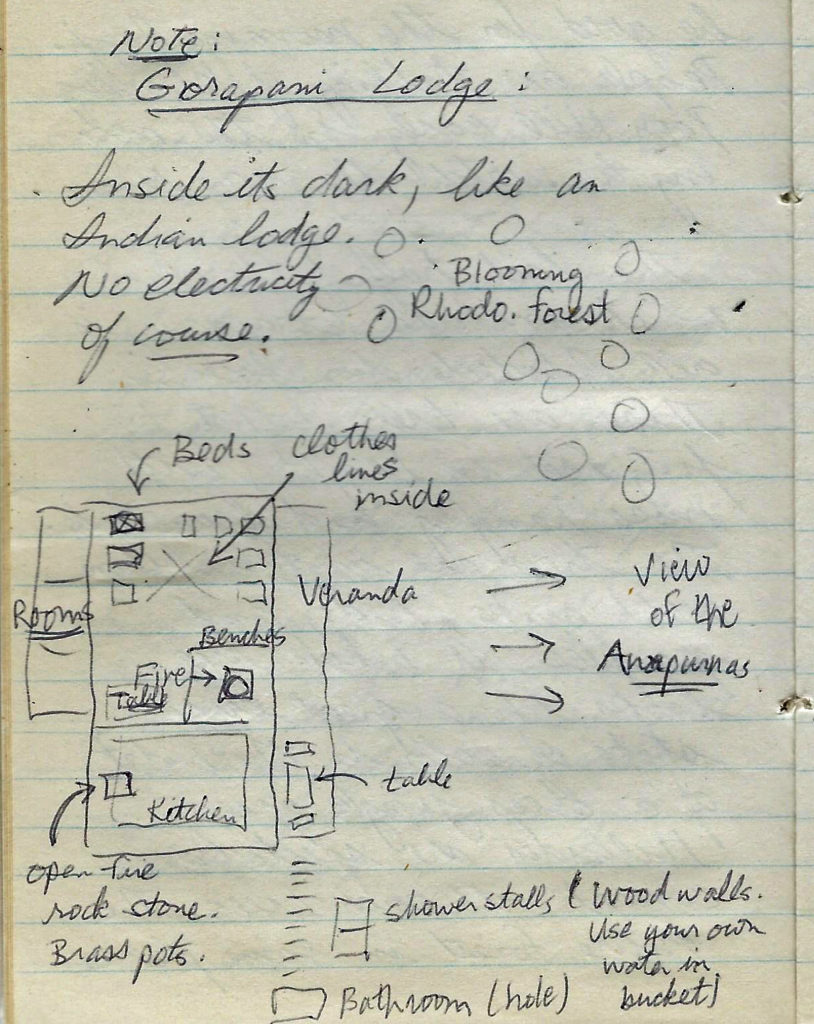

We overnighted at the Mountain View Lodge in Ghorepani at the end of the third day, the recommendation of my Kiwi friend, Grant, back in Agra. The village is nestled among the rhododendrons in a high saddle flanking a deep river valley to the west. From various parts of town there were full views of the peaks: to the northeast were Machhapuchhre and the Annapurnas; to the north, the Nilgiris; and to the northwest, the massive and notorious Dhaulagiri. All these monsters have elevations over 22,000 feet; Dhaulagiri is 26,795 feet. The peaks towered far above Ghorepani’s meager 9,300-foot elevation.

The lodge was thickly shingled. Its open fire in the center of the main room, surrounded by rough-hewn wood floors, exhausted smoke into the vastness of the living area. Without electricity, it was dark and cold like a medieval house. A small blaze was the sole source of warmth and its choking smoke penetrated hair, clothing, pack equipment—everything. Old brass cookware dangled from the ceiling.

Having no ventilating chimney or flue, the lodge roof oozed smoke to the exterior. From the outside it looked like the structure itself was afire. Chimneys apparently hadn’t yet been invented there. All the Nepalese houses I saw exhibited this system of smoke “ventilation.” After a time inside, mosquitoes and other bugs seemed far less interested in our smoky bodies.

All around were articles of trekkers’ washed and sweaty clothes draped on lines to dry. As a result, the woody sanctum smelled a bit like a high school locker room—a very smoky one. Not surprisingly, the innkeepers slept in a separate row of rooms behind the main building.

Without utility service, the toilet and shower facilities necessarily resided outdoors. The toilet was a hole in the ground at the end of a slippery path some distance away from the main building. You approached the hole with care.

The shower was a bit closer to the lodge, on an elevated, wooden platform surrounded by a cage of vertical branches connected together by wire and twine. The cage wasn’t particularly private. One entered through a swinging sheet metal door on wire hinges. The entire structure was some five feet tall. Standing up was out of the question–unless one didn’t mind exposing themselves. Privacy was only accommodated in the quad-killing squatting position.

One washed with either a single bucket of icy water from the nearby well or, alternatively, an icy bucket with an added pot of boiling water purchased from the innkeeper. Poured together, one bucket became the sole source of tepid water for both soaping and rinsing. Washing this way became a practiced art and, when one was so engaged, most other trekkers politely looked away. Privacy or not, one dared not spill their bucket.

Marianique jumped right into the process. I had to follow suit or look like a prude—and continue to stink after three unwashed days on the trail. I stepped in, latched the gate behind me, delicately balanced my water supply, poured a bit of water on my head, and then commenced shampooing my longish mane. Soap went into my eyes. Then I couldn’t see. I nearly fell over inside the rickety contraption. The rest of the washing was a half-blind, teetering curse-fest on a slippery surface, in full paranoia that I might fall and upset the water supply, or simply run out before the soap was removed.

Daily hygiene was essential. It wasn’t just washing, but brushing teeth without ingesting the water, ensuring that food was fully cooked, constantly hydrating, occasionally cleaning and drying your clothes, and addressing all injuries with the proper first aid. You had to be vigilant. Those who weren’t paid a price.

A distraught Canadian girl sat inside the lodge during my entire stay in Ghorepani. She had the yellowest eyes I’ve ever seen on a human. She was feeble and depressed, knowing she had the telltale symptoms of hepatitis. Everyone else knew too, but nobody could do much for her—except to advise that she hike out. But she didn’t want to leave. She said she was on her way to the mountains. She wasn’t sure what contaminated substance she ate or drank. But her trip was over. We could all see that. What she really needed was a reprimand and a hospital.

As my own safety measure, I carried a thermally-insulated liter thermos that I purchased second-hand in a Kathmandu trekking store—something I wasn’t sure I really needed. Beginning the second day, however, I realized that water was not to be trusted. Not even from the rivers. You never know what village lay upstream. Thus my hydration became a process of buying refills of hot green tea or chai multiple times a day—always peeking into the kitchens to be sure the tea water was boiling over the fires. I drank nothing else for the entire trek.

*

Later in the afternoon, ominous dark clouds gathered and then let loose upon the village. Lightning arced down nearby and thunder echoed between the peaks. Our lodge was far from impervious to the rain. Its multitude of sieve-like smoke ports acted as rain scuppers into the inner sanctum. One needed a rain hat just to stay dry inside.

With the rains came the cold winds. Eventually the travelers all made their way back into their respective drippy accommodations to wait out the storm. Marianique and I huddled around the open fire in the main room like the rest of them, coughing when the smoke blew in our direction.

The weather in these mountains could be oppressive. It was sunny one moment, dark and violent the next. The Nepalese seemed to be a robust, tougher breed of folks than their Indian neighbors to the south, living a life further from civilization and in harsher elements. But “harsh” was a hard concept to evaluate here. Much of Southeast Asia could be described as harsh. Still, I wondered how many Nepalese died of sudden lightning strikes and rock falls from the fickle heavens above?