The winding death-ride in the old bus from Kathmandu ended when the betel-chewing driver swung off the potholed pavement, bounced into a gravel parking lot, set his brake, yanked the door lever, and poured us out through a hinged opening that strained to fully open. Out we stepped—a writhing mob of hippies, vagabonds, and mountain-seekers—into Pokhara, the steamy trailhead town of central Nepal. Thirty bus-weary passengers were dumped into the glaring sunlight where we could stare in wonder at the ice-capped wall to the north. This was where I would come to grips with my Himalayan fantasy.

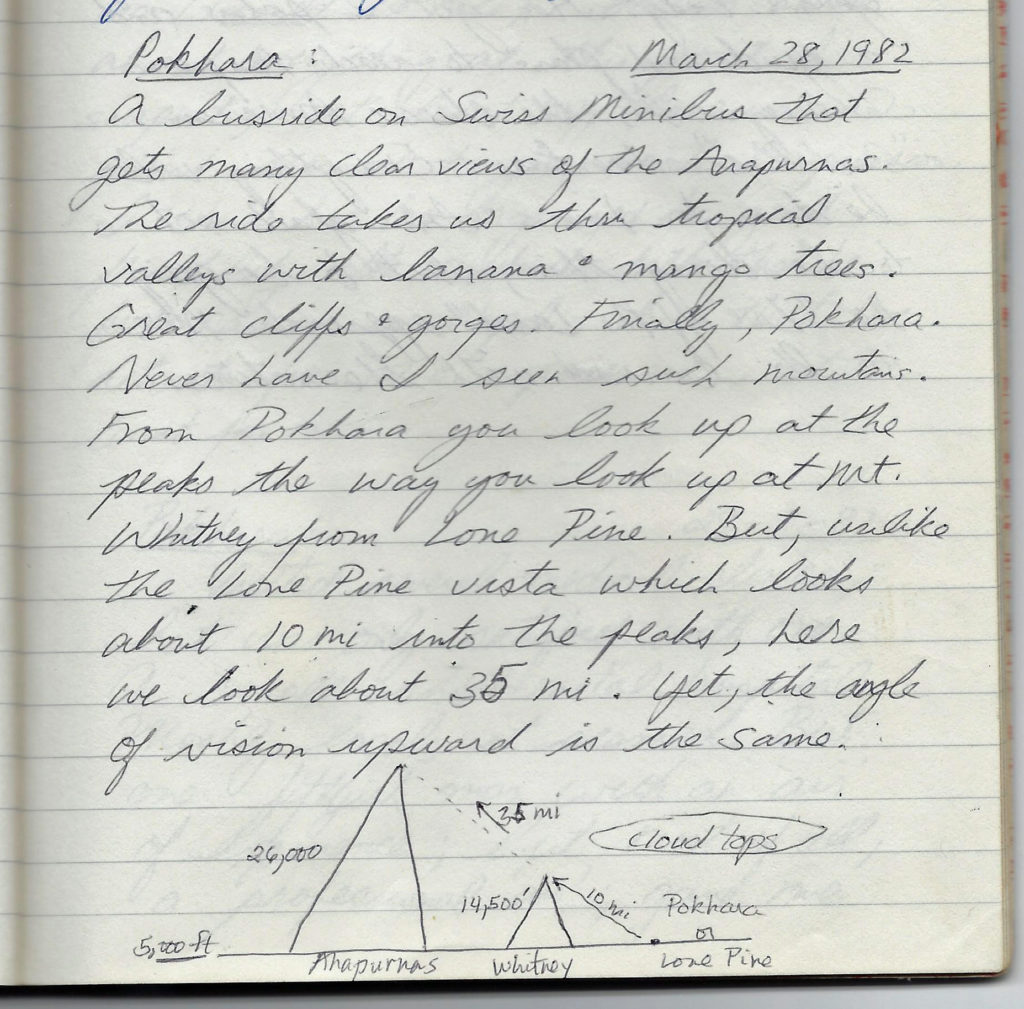

The all-day bus excursion of precipitous curves, brake-squealing downhills, and rough roads, with few safe places to pass, was stomach-churning. But it provided extraordinary views of the mountains. To the north rose a line of famous peaks that I’d heard about for most of my life. I tried to identify them on a map without becoming car sick in the process, but the bus often swerved during dangerous passes or ducked behind mountainous shoulders that blocked my view. Then I’d have to look forward and quell my gut. Yet, as if witness to a grotesquely tall giant among a throng of normal humans, I would turn to look again; my head back to the window. When we reached Pokhara, I hurriedly departed the rolling prison and happily breathed in multiple lungfuls of diesel fumes and dust.

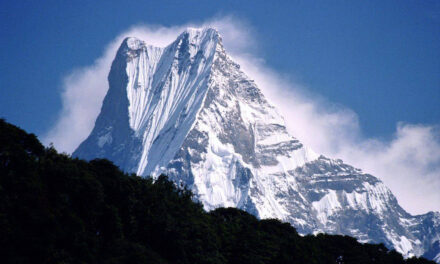

The din of Pokhara was not a match for Kathmandu, but it was still loud. My ears were assaulted by honking, yelling, and the roar of diesel engines. Momentarily directionless with my pack slung over my shoulder, I stood in the chaos and squinted up at the great peaks: Machapuchare, the Annapurnas, and Dhaulagiri. There they were. They took my breath away. And there I was: geared-up, energized, mostly vaccinated, visa-ed for a month, ahead of the monsoon, ready to go—and all just by happenstance. All because of a conversation I’d had a month before with a Kiwi in New Delhi. It had been planned like the rest of my trip; by the seat of my pants and the advice of near strangers.

Still, I still needed a hiking mate. I had no intention of walking into the Himalayas alone. So that had to be worked out. I figured it couldn’t be that hard. Mountain-bound tourists were everywhere, from everywhere, all skittering about in preparation like busy ants in a field of grain. Logically, it seemed that this staging place was the perfect arena for a loner to connect with someone—to bond up for a group mountain excursion.

I found a local room for a few nights, fed myself, and then wandered the town, with eyes and ears paying attention to the others around me. I talked to travelers from all over the world, all wide-eyed and brimming with expectations. Yet, what seemed easy wasn’t. Many of the seemingly well-intentioned hikers just whiled away the time getting stoned and drinking in the local establishments. Others clung to slow-moving or disorganized groups. Some didn’t know where they wanted to go. The process was discouraging.

As it had been in Kathmandu, most of the trekking groups were pre-arranged assemblages of close friends, married couples, serious climbers, or portered plodders. Many had set their bars low, or had ill-defined itineraries. Too many of the couples were engaged in the throes of testing romantic inclinations–or dis-inclinations. Everyone had different expectations. Wherever I turned, the companion options were qualified. Moreover, my aloneness emanated some kind of a big red warning. That weighed on me.

A day went by, and then two. I crisscrossed the town, visited the local bazaars, frequented the coffee houses, and took a tour of a local limestone cave. As naturally cheerful as I considered my demeanor, it was as if I was asking people for money. A friendly couple realized I was looking for packing mates and suddenly became spooked; a Canadian with great aspirations admitted he would need a porter because he’d never backpacked before; another guy was a serious climber and sneered at my Jomsom itinerary. Nobody was open to adding another member to their entourage—or if they did, I wasn’t interested. I became discouraged, then depressed, since this could very well be my once-in-a-lifetime chance to walk into the world’s biggest mountains.

Instead, I set myself back to planning: ignoring the larger issue of my aloneness.

Thereafter, I spent a day sizing up my various vaccinations. After visiting several unimpressive and dirty medical clinics, one fifty-ish doctor in a countryside Quonset Hut got my attention. He read my vaccination cards and opined that I was good on Typhoid and Hepatitis vaccinations, that Cholera was not an issue, and he was willing to refill my bottle of malaria pills. He thought a Tetanus shot would be most important so pulled out a large syringe and gave me a traumatic jab on the spot. Since I was in the company of some fifteen pregnant women who were waiting for the doctor’s services, and who had parted for me as I entered the rusting clinic, I kept a stoic smile on my face as I was punctured. They clapped when the doctor removed the needle.

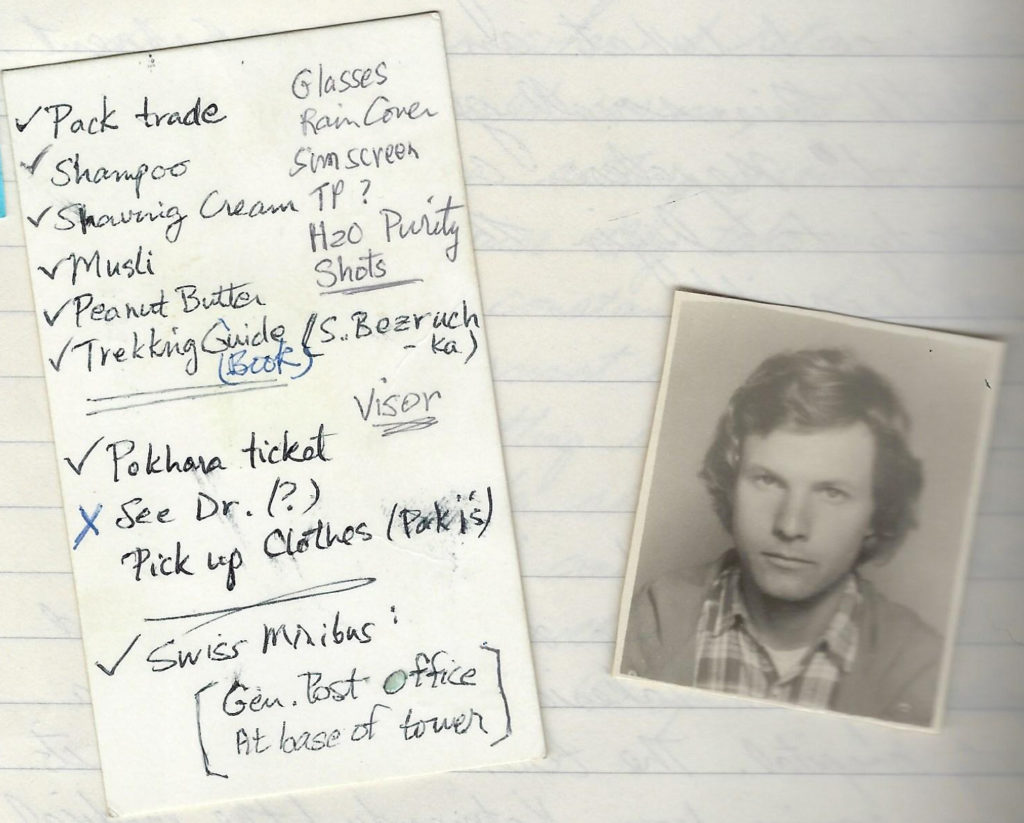

On the third day, I meandered about looking for those things that I had forgotten to pack. That’s always a challenge since one typically doesn’t identify forgotten items until one has left the station. In any event, I tried. That same day, I had a picture taken for my trekking permit (always to be procured at the very last minute, lest the permit expire before one returns) and finished purchasing a list of items I had started in Kathmandu.

On the fourth day, I had had enough. I paid for my room and loaded up my pack, exasperated with the search for a hiking mate and done with people who seemed closed off to assimilating a stranger. I didn’t need that crap; none of it. This trip–any trip into the mountains—required a free mind, a defined destination, and great flexibility. There’d be enough baggage on my own shoulders without the added burden of portaging the emotions and expectations of others. As for being solo, I had been that way for seven months since I left home after taking the BAR. I had always survived. This would just be another test of my fortitude and creativity.

Moreover, I’d done plenty of packing in the Sierras, so I was comfortable with carrying a load. Although it was bad Juju to enter the wilderness alone, I’d done so plenty of times for extended day-hikes and mountain scrambles. Especially after my father died. When backpacking, my companions had always been strong and motivated, so I was disinclined to merge with the slow, the complaintive, the inebriated, or the second-guessers. My goal was to hike to a point where I could at least look out into Tibet. I wanted a visual glimpse of the world’s roof. Maybe I’d even keep going–walk into the beautiful void. I had grandiose notions.

It all seemed simple enough. There were maps and the Jomsom trail was supposedly well marked. Indeed, that passage to Tibet was a thousand years old. Still, there were issues that could arise: injury; sickness; an early monsoon; the potential unavailability of food in the high areas; even the marauding Maoists. Well. Nothing ventured, nothing gained. That would be my continuing mantra.

*

My supplies were the product of a quick but methodical analysis. I’d read the trekking guides, perused the Kathmandu backpack shops, and interviewed a few of the returning trekkers. I could carry enough weight to accommodate most nasty surprises. My load contained cold-weather gear, a few packaged food items, a first aid kit, and even my luminous blue Saucony running shoes in case the leather mountain boots didn’t work out. I had a practical sense of what was essential.

My pack was a comfortable and voluminous exterior-frame Jansport, which I traded my smaller Millet pack for in a Kathmandu travel store. (The Millet had taken the place of a rolling suitcase that was sent home from Germany when I learned I had passed the BAR exam.) It contained clothes, a sleeping bag, rain gear, backcountry gadgets, and a few containerized foods like honey and peanut butter. I’d heard that the Nepalese villagers would provide bland indigenous meals, as well as lodging, so I required no bulk food supplies or cooking utensils, just warm clothes. The pack weighed only forty-five pounds, light for a long jaunt at elevation.

The Jomsom trail, rising from the rice paddies to the arid Himalayan shrine of Muktinath, was approximately sixty miles. It was a relatively easy hike by Nepalese standards and a common route for novice western trekkers. It passed between the Annapurna and Dhaulagiri massifs, with peaks in the 25,000 foot-and-over range.

Trek accommodations supposedly varied from bamboo sheds, to hewn wooden lodges, to rock huts. A few Nepalese Rupees, about $1.00 to $2.00 US per night, enabled one to eat and then sleep on a cot, a bamboo mat, or in the dirt. That’s what I was told, anyway. In reality, I had no idea what to expect.

The local Pokhara bus took me to the trailhead, where I stepped off, looked about, and then headed up the trail. I was off—albeit still alone.

*

The first hour of hiking under the April Nepalese sun was searing. Steamy rice paddies lay close by to the south. Shade was scarce. To the north, I caught occasional glimpses of the snow-capped Machapuchare, which loomed like an ominous presence, a twisted version of the Matterhorn. It was miles away, and frigid ice streamers wafted from its top. As water rapidly sweated out of me, I stopped frequently to let my acclimating heart stop pounding. But I also stopped to ponder my predicament. Where was my partner? This venture was akin to scuba diving. What I was doing felt reckless–I needed a buddy.

In a few hours, the oppressive weight of isolation and defeat invaded me. Any solitary hike could amplify feelings of separation. I knew that. I’d been there. But this was something else. I wondered why I was taking that path now. It could be dangerous. Proven survivors didn’t put their heads on the chopping block. So began a second-guessing of the entire venture. It was debilitating. I felt–or imagined–other hikers silently commenting, “Poor lad… all alone,” through feigned smiles. When I stopped to talk, those same trekkers seemed to keep me at arms-length, like I was a pariah. Maybe I was a pariah.

Logically my chances of finding a hiking pal would diminish as I pushed farther away from the trailhead. Half of me was already looking back–like Lot’s second-guessing wife. The inherently poor choice of barging off alone tore into me. It was probably impulsive. Yet, despite the strong urge to turn back and regroup in Pokhara, I kept on. I knew something favorable could happen—it always had. I had willed such things before and they had happened—for whatever reason. I might as well test that implausible notion again, once and for all. It was either loony bullshit, or a strange new reality that required verification.

No second-guessing, I told myself. No looking back and no turning to salt.

So I began to set my mind to work as I had on the Egyptian jet—to imagine, to hope, to urge a better scenario; to keep my current venture from crashing. It wasn’t so much that I wished; my thoughts just pushed for what might be. I needed a trekking partner–someone who could move along a decent clip, be pleasant, and remain at a reasonable arm’s length. A simple order, really.

Who was I kidding?

I’d told myself there’d be no more wishing–EVER. Years before I had made a wish; a bad one, out of anger, with a malevolent aim. That wish—or whatever it was—had come pass, as if I’d stepped into The Monkey’s Paw story in the Twilight Zone. The result was devastating. It made me step back from myself—to be far more mindful of what I wished for. Many years had passed since then, yet there were things that had arisen since; things that made me reconsider. There was the Abdul incident in Morocco where my friends and I had been drugged and threatened with knives. The jet. There had been uncanny incidents in Europe–with improbable results. Even back at home over the many years: so many hunches and happenings. Was it chance? Luck? My mind had pushed and I had survived. No harm, I guess, as long as one avoided malevolence. Do no harm.

So I sort of willed things again, silently, steadily, strongly, as I hiked upward into the mountains.

I passed innumerable hikers. Some were flailing in the heat. Avoiding curious glances, I looked ahead as if wearing blinders. My pace was kept intentionally slow since this was the first day in, of many to come. There was no reason to hurt myself at the inception. To distract my mind from the solitude, I focused on taking frequent drinks from the canteen, on tuning the tension of my pack straps, and of not twisting my still-soft ankles on the rocky steps.

As the trail neared the top of the low ridge that lay between Pokhara Lake and the mountains, the entire range came into view. I stopped and took it in. The great vertical massifs of ice and rock seemed to be beckoning, despite all my misgivings.

Damn the torpedoes, I thought.

A great inner smile came over me.