Balancing atop the wobbly step-stool, hefting a brimming watering can upward with my quavering arm, I strained toward a thirsty cactus jammed on a shelf that was too high to easily reach. It wasn’t that the greenhouse needed plants up there—it had plenty of space. It was that the shelf’s height gave the rattails and hanging lepismiums loftier perches, letting their waxy stalks and flowers hang dramatically, like living tapestries; to me, a worthy concept.

But I’d overfilled the two-gallon can, and the plant was at the very limit of my outstretched appendage. As I defiantly pushed it upward, the spout swung right, barely missing a cluster of living pin cushions beneath the ledge—a close call. I winced at the thought of toppling those plants to the ground and pulled the can back. Maybe I should go down to the barn for the ladder.

“Damn it!” Gritting my teeth stubbornly, the impetuous other part of me commanded that my skinny, fourteen-year old arm should darn-well rise to this watering occasion. To assist my faltering effort, my other hand let go of its stabilizing grip on a two-by-four support post and flailed upward to help its companion; a bad move. I wavered, the stool teetered on the gravel floor, and my arm failed.

The weight of the can stopped its upward motion and the spout swung to the left, striking a peanut cactus in its clay pot. As if in slow motion, I watched the pot tip, roll off its ledge, fall—losing red flowers in the process—and spiral down toward the four-foot cholla plant standing next to me.

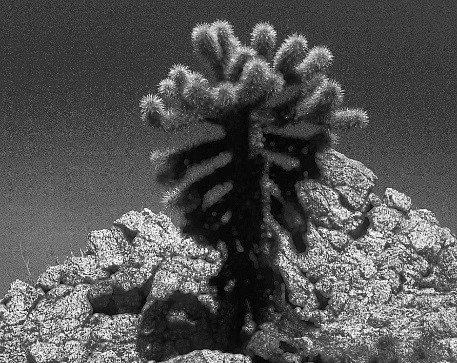

“Oh God,” I groaned! I’d painstakingly grown that dangerous skewer-fest from a living stem carefully removed from the Mojave Desert several years before. It was my beautiful, nasty cholla, the one that meant certain pain if you touched it. It was a menace. So I never touched it. There were special homemade tools for that.

*

“Jumping Cholla” is the common name given my nasty plant. Cloaked in vicious, barbed thorns, chollas look like silvery sculptures of toothpicks all glued together. Mine occasionally skewered a fly that buzzed in too close. The cholla doesn’t actually jump, though. But if it gets jarred severely enough, it will whipsaw to and fro, and can jettison its spine-covered branches in any direction from the main trunk.

*

The plummeting peanut cactus struck the cholla with a sharp jolt and bounced to the ground, its pot shattering. I helplessly watched the explosion of terracotta, cactus parts, and potting mix across the gravel bed of the greenhouse floor.

In reaction to the impact, the cholla sprang back violently, whipping about as if trying to slap back at its assaulter. It then jiggled crazily for several moments like a spine-covered Jell-O tree. Looking down, I noticed that the impact had dislodged a spiny branch from the trunk of the plant, which had simply vanished. I didn’t immediately see it, only its absence from the bigger plant. Where did it go?

The entire episode had seemed instantaneous. The cholla had ejected its piece with lightning speed.

I expected to see the missing piece next to the remains of the blooming peanut cactus, or maybe stuck to one of the two-by-fours supporting the redwood benches. But it wasn’t in either of those spots. I craned around, wondering what its barbs might have attached themselves to.

Then, as I further twisted around on the stool, there came an unusual stinging sensation in the side of my leg.

*

Collecting stuff is an odd endeavor. I’m not sure when I began collecting cactus plants, but it was well after I’d become bored with collecting stamps and rocks.

Mom had directed me toward stamp collecting one summer some three or four years before, giving me an envelope full of old postage stamps and a couple of albums that needed filling, insisting it was “exceedingly educational” and even a little interesting. Each stamp had to be identified by country and date, located and positioned in a big binder, then carefully glued in.

It began fun, a little like detective work. The problem was, every time I thought I was done with the project, Mom dredged up more stamps to categorize and place, buying me more blank albums in the process. Then it became a grind—busy-work.

After that, there were the rocks. The more we rummaged through old mining tailings and geological sites, the larger became the box of rock rubble I accumulated out in the barn. Some were beautiful: crystals, geodes, jades, all colors of stones.

Dad bought me a geology kit so I could identify my specimens. The flashiest ones were labeled, mounted on plastic, and placed on one of the cleaner storage shelves on the barn’s second floor. They all looked great. But when that task was over, they were altogether boring—like albums filled with stamps. They just sat up there quietly and collected dust.

In the meantime, I kept running into cacti.

*

The cholla branch—all six spiny inches of it—was firmly attached to me like some terrible desert leech. Ten or more of its spines were embedded into my calf, the barbs holding fast. It bounced like a floppy appendage when I tried to walk, each movement imparting a twang of pain.

“You idiot!” I spouted to myself.

I reached down as if to brush it away, but then I quickly stopped myself, remembering the story of the Tar Baby: one touch, and Brer Rabbit was held fast. I imagined my hand stuck to the devilish thing, then having to walk back to the house that way—as if a Chinese finger trap were connected to my leg.

I stood and silently pondered my predicament. The weight of the cholla piece alone was causing my skin to pull away from my leg, little volcanos of flesh rising up at each spine. I looked for something to detach it. There were numerous greenhouse tools: trowels, scissors, sticks, gloves. But none of those implements solved my need for removing it without impaling myself further.

Dad was over in the barn. I could call for him and he’d eventually come running. Then I imagined how he’d react. He’d probably take one look and smile, maybe burst out laughing. Then, as he did with Band-Aid removals, say something like “This might hurt” and yank it unmercifully. I cringed at the thought.

I could call Mom. That might be a less severe option. But then, she’d likely be squeamish and then deferentially call out to Dad. After that, they’d both have a good snicker. The end result would be the same.

Crap!

*

Everywhere we went, we seemed to run into cactus plants. They were curious: ugly, beautiful, and dangerous all at once. Eventually I began to bring them home to Placerville.

The plants captivated me, even though I’d been stuck and jabbed while picking them, transporting them, and manipulating them into their terracotta pots. They were so hostile on the outside, yet so vulnerable inside with their soft watery cores. And from those odd plants came the most amazing blooms. Best of all, if you forgot to water them, they rarely died.

There was another thing: cacti were a bit like some of the people I knew—vulnerable inner souls with thorny protection on the outside. Maybe I related to that.

My spiny plants lived in a greenhouse I built with money earned working for Mr. Al Veerkamp at his tree and plant nursery in Gold Hill, a few miles from home. I rode to and from work on my motorcycle, making a little spending money and learning how to make things grow

When I let it be known that I needed a place for my prickly friends—an open-air structure covered with light-filtering lath, which could be covered with plastic in the winter—Dad agreed to help. Together we concocted a simple design: frame, lath exterior, redwood benches, and crushed gravel floor. Dad made me figure out how all the components would fit together, and what I’d need to connect them. It even had a hinged door to keep out the nighttime critters.

*

The cholla dangled menacingly from my leg, as if taunting me. Part of me knew what I had to do; it wouldn’t be pretty. Another part of me wanted to look away and ignore it.

Moving slowly, lest I painfully work the spines deeper into my flesh, I grabbed the old steak knife I used to pry plants out of their root-bound containers. It was rusty but had a sturdy blade and a firm handle. I carefully slipped it between my calf and the cholla, between stickers so as not to snap off any of the embedded spines. Then I gently lifted the unwanted attachment away from my leg. It didn’t budge—nothing! The skin pulled away a half-inch or more at each barb. I pulled harder. Same result.

Retracting the knife, I leaned against the redwood bench on which all my little starter plants sat in their little clay pots, and took a breath. A wave of light-headedness swept over me. This would get far uglier before it got any better.

I wondered what a doctor would do. Maybe I should try to snip off the spines, one at a time. But the tool for that procedure, the wire snipper, was down in the barn. That would mean a long, painful walk, and the likelihood of running into Dad—I already knew that ending.

*

When our dog, Blackie, loped home one day with a nose full of porcupine quills, she came to us whimpering and snorting, perhaps comprehending that only a human could help her. Her nose ran and she wheezed. She pawed at her face as if to wipe the quills away, but to no avail. The quills were in deep.

We all gathered around Blackie in the kitchen and stared at the four little black spears, each deeply anchored. None of the spines would budge for any of our probing, pulling fingers. She winced when any of them were touched.

Always up for a mechanical challenge, Dad solemnly tromped to the barn for some of his automotive tools. He returned to the kitchen carrying several old rags and three sets of pliers. First he tried the needle-nose set, which promptly lost their grip. Next he gripped one of the quills with regular pliers while Mom held Blackie by the neck. He gave it a yank. Those pliers slipped from the quill, leaving Blackie crying and skittering on the floor.

Dad then put down the regular pliers and reached for the vise grips. They were the big guns of handheld pliers, locking onto their target with a distinct click. They were heavy, too. Using one of the rags, Dad carefully wiped off the engine grease as if he were following some sterilization protocol in the ER. The car doctor was now the dog doctor.

I wrapped my arms firmly around Blackie’s neck, and Mom got a grip on her hind quarters. Once she was immobilized, Dad took to his knees and carefully clamped the vice grips on the smallest quill. Blackie winced and squirmed when it locked on, but we held her fast. Then Dad looked up at both of us with an expression that asked, Are you really ready for this? We were.

Holding her snout closed with his free hand, Dad gave a tremendous yank. Out came the first of the four quills. Simultaneously came one horrible, bloodcurdling yelp from our four-legged best friend who’d trustingly sought our help. Where the first quill had been was now a little blob of bloody flesh that the barbs had dragged out. It was nasty. Mom patted off the gore with a wet paper towel and calmly whispered, “Poor girl! You’re okay.” Our trembling canine pal looked utterly dejected. We felt a little that way, too, having inflicted so much pain. Little did she realize that there were still three more quills to go, all bigger and deeper than the first.

*

Remembering the porcupine experience, I paused to size up the dismal options for disconnecting the cholla from my leg. Blackie’s desperate yelping was firmly ingrained in my memory.

As I turned to reconsider my rudimentary greenhouse tools, I found myself talking aloud—to myself. I did that sometimes.

“Nice predicament!”

“Shut up!” I hissed back to the first voice.

“You can do this.” My head felt light again. The sparring voices were getting testy.

“Put your leg up here!” the first one barked.

My leg obliged. Now I could view it better. I stood there awkwardly, one supporting foot on the greenhouse floor, the other up on the bench, my calf at waist level. The cholla hung by its many vicious anchors. Then I, or that other part of me, reached down and picked up my rusty greenhouse scissors.

“What?” I don’t think so!” I blurted quietly to myself.

“Insert the open blades between the leg and the cactus,” said the other voice. “Then yank it away holding the open handles.”

My hands slowly and carefully inserted the blades as ordered, between the calf and cholla, and between the anchoring spines. I gasped when I bumped one of them.

“Don’t be a wussy—you know what to do!” came that other voice.

I’d tried that concept before—sort of. It hadn’t worked. My pain center made me hesitate.

In that awkward position, I craned around to see who might be spectating. My brain imagined Dad. That’s all I needed! He’d come over and make a mockery of the whole extraction process. He wasn’t watching, but was out on the front lawn by the house, several hundred feet away in clear view. Then he looked in my direction—maybe considering venturing over. No! Both parts of me took in that possibility and adrenaline rushed through me.

Before I was fully turned back to face my stickery plight, there came a sudden lightning bolt in my calf as if a glowing cattle branding iron had been thrust onto me.

“Arghhh!” I moaned.

It was the feeling of fire and wasps, combined. That other part of me, unwilling to listen further to the moderate part, had violently yanked the rusty scissors away from my leg with the cholla branch—without warning.

Ablaze in pain, I saw my calf was now free from the cholla’s grip. Blood was drizzling out of me from a multitude of red spots where little blobs of flesh had been pulled out in the process.

“Craaaap!” I bellowed, clutching my throbbing leg. The pain took my breath away. “Why’d you do that?” I complained to myself.

“You’re welcome!” came the silent reply. “It worked for Blackie, you may recall.”

My head swam.

“We can take the soldering iron to those little blobs that the barbs pulled out.”

With that, I sat down on the step stool, put my head in my hands, and focused on regulating my breathing.