It was April and the afternoon air baked from the pre-monsoon forced-heating of the Indian interior. Even the trees seemed to wilt. Cows wandered the eroded streets between the rickshaws and emaciated townsfolk, or lay chewing in intersections, or poked their heads into sidewalk cafes. Cars fitfully sped about, honking, avoiding the cows but not the people—they seemed to aim for them, or for the monkeys. More than once I ran for my life, narrowly missed by a taxis barreling by in a cloud of dust.

Everywhere, bony dark-skinned people in white muslin carried, peddled, sharpened, washed, cooked, and swept. Flies alit on every piece of exposed skin until their tickling sensations became muted. All this, under a dusty sun that radiated heat like it does in August in Bakersfield.

My Agra backpacker’s budget hotel was probably a hundred years old, its exterior a flaking veneer of whitewash. Meagerly furnished with tile floors, ceiling fans, rope beds and two flea-ridden dogs, inside one could evade the glare, the beggars, and the wandering merchants. The proprietor stood guard near the outer doorway, only letting in invited guests.

From my third-story room I could see over most of the local rooftops, so commanded a lookout, of sorts, upon everything simmering under the sun. The roofs were an elevated, chaotic plane of mercantile organization, not just a shield from weather but an open-air industrial zone overlaid with things drying and bleaching, aging and ripening, stored, and even forgotten.

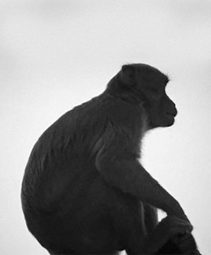

On the second day at the hotel, the calm of a sweaty afternoon nap was broken by the sound of children screaming. The noise came from beneath my balcony where a band of wild monkeys was accosting a group of kids who were eating bread scraps under the shade of a tree. The children were cornered against a wall.

From my little balcony I could see that the hungry simians, easily as large as their young human counterparts but immensely stronger, threatened the kids with bared canines. They wanted the bread. One of the littlest children was shrieking. A larger kid picked up a few rocks and began pelting the animals. When one of the projectiles struck a blow to the cranium of the largest monkey, it and its band retreated across the street and over a wall.

The childrens’ face-off against the meddlesome monkeys hadn’t raised an adult eyebrow. It was just the way it was there. Other activities carried on without interruption: truck drivers sped by honking, restaurateurs waved at flies while serving muslin-clad patrons, donkey and hand-drawn carts bounced along, and rickshaw drivers peddled frantically around a multitude of obstructions. Blaring Indian music filled the air.

As I stood on the balcony, I saw fruit dryers spreading out dates, bananas, and mangos on a nearby rooftop, all arranged under the sun on rugs and straw mats. The fruits were meticulously organized in a single exposed layer. On another roof the fruit-turning process was underway, a sluggish hunched-over hand-and-arm exercise in the mid-day heat. The turners moved across the expanse of fly-ridden food painstakingly, many bushels in their care—enough, perhaps, to supply a dozen families’ annual consumption.

In the meantime the children had drifted away, having finished their bread; the monkeys vanished between the buildings. The food turners eventually finished their tasks, as well, and disappeared off the rooftops. The peace of the hot afternoon regained, I returned to my position of sweaty recline under a squeaking ceiling fan.

*

I pondered the things so many people put up with in the world. We have it so lavish in the US with our technology and air conditioning. We simply flip a switch or turn a key. Most of us can buy ourselves any climate we desire—warmer or cooler, in a building or a car. In India, hundreds of millions don’t. If it’s sweltering outside, it’s sweltering inside.

Moreover, American food comes wrapped in plastic, in sanitized cans or cold storage, stamped with dietary descriptions, and labeled with microwave cooking instructions. It’s all so easy. We don’t prepare the things we eat—other than to heat it—so haven’t a clue how it’s grown, or plucked, or shelled, or cleaned, or preserved. Most of us live in cities so far removed from agricultural production that we have to be taught that food doesn’t get manufactured in supermarkets.

*

Minutes later I heard another commotion, so returned to the balcony. Two buildings away, a lone monkey stood atop a rooftop, having just toppled a stack of metal pots. It was one of the adults–the one that had been stoned by the children. It cautiously peered about in a crouched position, as if it were a periscope on a submarine in hostile waters. Then it stood upright and made a full 360-degree visual reconnaissance of the entire area, squinting against the sunlight.

The monkey’s scan was methodic and continuous, but it stopped when its head was aimed in the direction of the drying fruit on the nearby rooftop. Its body went rigid and its motions became nervous, jerky, as if it might be in someone’s gunsight. It looked around again several times, eventually spotting me watching from my balcony. We stared at each other, assessing who might do what, who might move first. I kept still, hardly breathing. Then the monkey disappeared–temporarily.

Less than a minute later, the entire band of simians poured upwards over the far edge of one of the fruit-covered rooftops. Like a wave, they rolled out en-masse, then stood gaping and looking at the drying food, blinking as in disbelief. They shot quick glances in every direction, not quite sure that they‘d discovered such a plentitude of untended edibles.

When a crow flew overhead, the monkeys all nervously ducked and scattered as if to avoid an incoming projectile. Their human tormentors weren’t that far away. But they quickly realized it was no threat, just a bird. The humans were absent, huddled away from the heat under the roofs. A few seconds later the youngest monkeys moved in to smell, then to touch, then taste, then eat.

There were six monkeys in all: four adults, and two juveniles. The adults each appeared to weigh forty pounds or more. They had miniature, hairy human faces with large, Andy Rooney eyebrows, brown coats, long fingers, and snake-like, tufted tails.

The young monkeys were tiny; cat size. They launched into a feeding frenzy, rushing to the fruit and crammed it into their little mouths as fast as their little hands could grab it and stuff it in. Their cheeks quickly became so distended they could barely chew. One of them gagged, spit out the load, and then stuffed in more. It was monkey Thanksgiving.

An older monkey grabbed several bananas in one hand and scampered away off the roof, perhaps to cache it away in a secret place. It disappeared over the far side of the building. Another young adult followed suit. The intensity of the thieving band increased a level of magnitude when they realized they weren’t being watched—only I saw them.

Two of the adult monkeys took a different approach. They didn’t eat. Instead, they began to carefully load themselves with the largest fruits within reach. They layered several big bananas in the cradle formed by an arm held tightly against their respective monkey chests. The bottom layers were then covered with more layers as if they were gathering a load of branches to take to a bonfire. Soon each of the two was holding an armload of ten or twelve bananas, using both arms, as if each were a living shopping cart.

As their loads grew, it became increasing difficult for the two monkeys to add additional fruit. Each reach-down-grasp required them to bend and tip. The leaning over was so destabilizing, they had to use their little chins to keep the gathered heaps from toppling. I could almost see sweat on their little brows as they struggled to amass the largest armloads possible.

Neither monkey ceased piling on more. Eventually, each time one reached down to grab another banana, it dropped one or more from its arms. When one reached for a large fruit that had fallen, it dropped three. That went on for eight or ten rounds, in silent frustration. Neither monkey realized the problem was not one of dexterity, but of exceeded capacity. It was an impasse born of their own inherent greed for more.

A third adult joined in and confronted a worse dilemma. It copied the other two, but loaded up with incompatible fruits: bananas and mangos. The mix stacked poorly and that monkey’s entire load toppled to the rooftop repeatedly. As careful as it piled the jumbled mixture within its clutches, it then lost the mismatched load in a crashing, rolling, bouncing jumble. Then it started over again–over and over.

*

There is something exceedingly human about taking more than you need. On the one hand, it’s the mind overruling the stomach, fed by notions of future requirement and expectations. From another view, it’s greed trumping need. Humanity only aspired to manufacture, to create art, to write, because it had enough food in storage to take a breather. When you stop hunting and gathering, you aspire to more creative ventures.

The monkeys hadn’t yet taken that evolutionary route. They’d gotten stuck in the hunting-gathering stage. Here were our close relatives exhibiting counterproductive resource collection–taking too much to haul away, an issue we’d gotten through. They were demonstrating their genetic dead end. Maybe.

On the other hand, I wondered if these monkeys were on their way toward a higher simian form that might someday take out a home mortgage that was unaffordable. Perhaps they’d have too many children to attentively love and support, just because they could. Then maybe they’d help deplete all the rest of the earth’s resources–make it look like the denuded landscapes of Southern Europe, or North Africa, or the Middle East.

*

It was at this moment that the monkeys’ pilfering was discovered. A child of one of the fruit purveyors came upon the scene–quite by accident. He’d climbed to the rooftop to retrieve an article of clothing. When he saw the thieves he tried to shoo them away by yelling and raising his arms, but the monkeys were big and he was timid. A few of the younger monkeys fled, but the adults stood their ground.

The three frustrated adults, still working on overloading their respective arms, noticed the human child but were hardly distracted, still fixated on their overzealous gathering. They continued to grab at new fruits, trying not to drop the last. Sadly, none of the three had yet eaten anything, much less removed any fruit from the rooftop. One dropped its entire load when it saw the boy and had to recommence stacking all over again. A moment later, another dropped a good half of its load.

The wiser old monkey that had, by then, taken three smaller loads of bananas off the roof, promptly ran at the boy. It screeched and displayed its sharp incisors. The child, small and defenseless by comparison, fled screaming. Sensing their discovery would soon precipitate a human intervention, the young monkeys rushed back in and continued to gorge themselves. Despite that, the incompetent grabbing, stacking, and dropping by the three adults continued unabated.

Finally the first adult Indian man appeared on the rooftop and squared off against the marauders. Two other men promptly joined him–none looked amused. It was hot and they were agitated at the jumbled mess of food. Their afternoon shade time had been interrupted. None of them, however, appeared eager to rush into battle.

The three frustrated adult monkeys, now busted, stood up and screeched. They bared their teeth at the men, thrusting forward dagger-filled maws. All the fruit they had fumbled with was dropped at their feet. The humans stood together glaring, facing off, but still did not advance. Then the men yelled in unison and waived their arms. So did the monkeys—right back at the men.

One of the men then jumped forward waving his arms. Two of the monkeys did the same at him. Another man picked up a stick and waived it threateningly. One of the adult monkeys grabbed a banana and threw it at him. The other two adult monkeys, having lost their respective loads, began picking up fruit and faced off against the men defiantly.

That’s when the food fight began.

The monkeys flung everything at the men that they could put their fingers upon: the fruit, the drying mats, and the rocks that held the mats in place. The men first backed away, waving their hands at the monkeys as if to say “no” to the idea of fighting with the valuable food. They wavered between recovering the food being thrown and advancing in an all-out frontal attack. The food was too important to just throw away.

Despite the human challenge–the men being far larger than their opponents–the monkeys nevertheless realized the terror they instilled. They were strong and they could bite. So they escalated the flinging and baring of fangs. Food flew like a Three Stooges movie. It was flung in all manner: direct fast-pitches, over-the-head heaves, and wild off-the-rooftop lobs. The screeching of apes and screaming of men overpowered the autos and trucks and other background noises.

A crowd formed on the street below. Faces looked up toward what could be heard, but not seen. Passersby were curious, and stopped, pleased at food raining down upon them. Falling food was snatched up and stuffed into clothes and bags. Children picked it up and ate it. Everything raining from the rooftop quickly vanished.

Atop the roof, the battle gained ferocity. The adult monkeys advanced aggressively on the men, snarling and backing them toward one corner of the precipitous roof edge. Men and monkeys both jumped about defiantly.

The cornered men finally yelled to allies below and were tossed up some monkey-battling clubs. With their new weapons, the humans swung, jabbed, and poked at the most aggressive monkeys. But, their swings were tentative and they never got close enough to make contact. The monkeys continued to lob fruit. The feuding species, collectively, threw away or smashed most of what had been set out to dry.

More humans eventually arrived to reinforce the original two. Then, in apparent frustration, the men began to throw back the fruit. They threw rocks and sticks too. Five men now made up the human force. The monkeys wavered and then began to back off, finally moving to the roof edge, the wall, where they stood their ground defiantly. They still screeched, jumped, and bared their teeth, but a little less menacingly. The men screamed back and bared their teeth. Then one man intercepted a monkey’s head with the end of a long knobby stick. There was a dull thud and yelp. That monkey abruptly vanished.

Two men then advanced on the other adult monkey that had squared off against them moments before. That monkey was hit by a rock in mid-screech. It leaped off the roof making a wounded, human-like noise.

With angry men advancing on the rest of the monkeys, the remainder of the band turned and fled. As they left the roof, the men continued to throw rocks and sticks at the retreating animals. The last monkey finally fled over the edge–its tail flicked like the final green flash of the setting sun. The humans had won.

But then the men confronted the battleground. It was a disaster. Food was smashed and bruised. Most of the larger fruits were gone, either thrown or taken. The men were downcast and accusatory. One pointed a finger at one of the others and delivered some type of a Hindi tongue-lashing. The recipient flung back his own insults and accusations, then yelled at the crowd down below. Human voices remained raised and agitated for the better part of an hour. Eventually they all began the task of picking up what was left. It wasn’t much.

*

The monkeys’ raid had been successful for the juveniles. The little ones had stuffed themselves and were likely now huddled away sleeping, dreaming. Not so for the three greedy adults, however—for all their efforts, they took home nothing but empty stomachs, damaged egos and bruises. They could have been stealthier, more disciplined in their takings like their elder, and they might have succeeded. But they chose to take too much, to squander the opportunity, intoxicated in their imagined plentitude.

Wilderness House Literary Review 10/4