Sprawled out on my back, before me lay—of all things—a tropical beach with frothy, white waves rolling in from a blue sea. There were palm trees, birds flittering about and the constant roar of the surf. Not deafening. Soothing.

My lungs breathed in the smell of the ocean. Gravity pushed me into the warm sand like fingers pressing a pie crust down into a baking pan. I could barely move.

Where was I?

There were other sounds too, but I couldn’t discern their nature or direction. Were they from the birds? It was too comfortable to delve very deeply into the mystery.

*

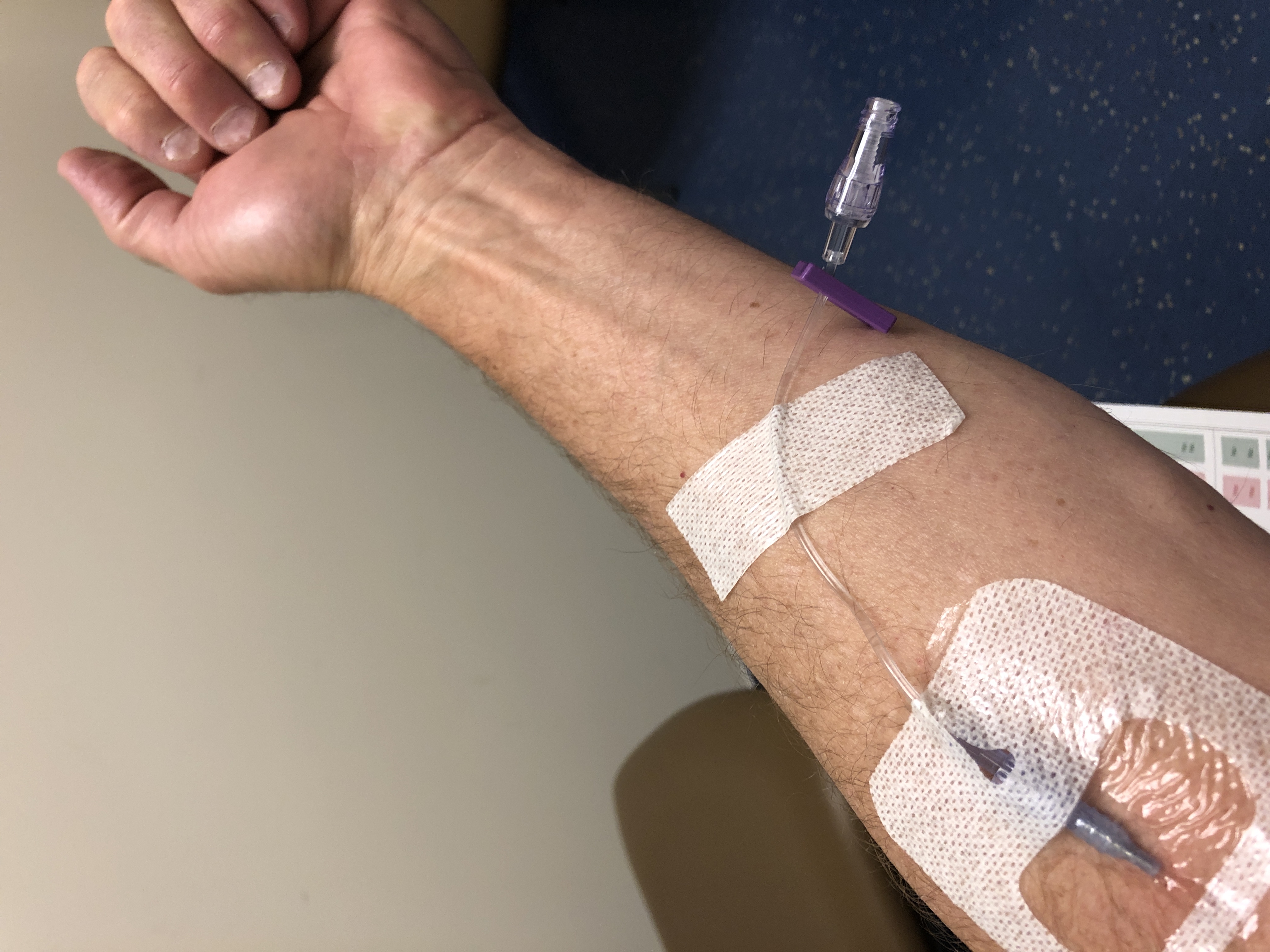

Pushed from behind, atop the green Alta Bates gurney with rolling IV rack and its attached saline drip tube bouncing alongside, I had pondered what I was in for. “Eye surgery” rattled around in my head. Hadn’t had that experience before. My pulse raced.

Didn’t really want to have this particular experience. Ever. Or to have large spiders sink their fangs into me, or piranhas chew away my flesh, or to fall into a volcano. Not on my list.

I’d entered the hospital expecting to remove my shirt, to sit in a special chair, get an injection and leave an hour later after a routine “retinal peel.” Nope. The pre-op attendant had peeked in at me and advised, “Fully gown, Mr. White. Then please follow me for placement of your port.” Ugh, I’d thought. Back to the races.

I was reminded of my major surgery to extricate a pancreatic tumor just a few months before. That was something: anesthesia; five days in recovery, a drain tube; pain; months of recovery. Yet in a way, that had been one of the most amazing adventures I’d ever had. The medical staff were supportive and kind, and the surgery process was out of the future. It was a venture into curiosity and awe within in a grand UCSF temple of medical science. Came through with a few less organs, but clear of the weed that had infected me. Small price, all that—for my life.

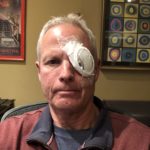

Figured the eye experience should be simple by comparison. Wanted it to be simpler. This was my darned EYE, after all; one of only two visual portals from my brain to the world I so cherished looking at.

My gurney-man rolled me down a long hallway to a large set of operation room double-doors, then stopped and proceeded to look inside. He scratched his head.

“Not here, I guess,” he stammered. “No one here and the lights are off.” He then moved to the back of the gurney and began to push again, this time in a different direction.

The gurney rolled down another long hallway toward another double-door entrance. We rattled and jiggled along, and then stopped. Those door windows were dark too. Another empty surgery room.

“Well, this is odd,” the man had said.

*

As I lay comfortably in the sand, there were still those noises I couldn’t quite ascertain. They sounded oddly like voices and came from above me, yet the sky seemed blank. Blue but blank. The birds seemed to have moved off, so what I heard must have been from another source. I pondered that.

Confused, I simply took it in: the undulating waters; the warmth; a light breeze; the light. A beach as real as any, yet foreign to my databank of beaches. Where was this place? Were there clues right before me?

Another wave crested, rolled over and broke into whiteness and my attentions forgot the questions and went back the sea.

*

My gurney-man had finally stopped before a third set of double doors, these with bright lights emanating from the glass windows.

“We’re here,” he said, and pushed a switch on the wall. The doors opened with a pneumatic “whoosh” to a room busy with bright lights, stainless steel equipment and medical staff.

Everyone in the operating room was blue-gowned, masked and gloving-up as they readied for my event. The place was spotless. My gaze went from the staff milling about to the fascinating lens-clad contraption hovering over the operating table. Questions immediately began to foment in my brain. What does that do? What is this for?

A nurse had looked up and smiled. “Welcome, Mr. White.”

Despite the bright environment, I had rolled into a virtual freezer, the AC having been apparently set less for comfort than for freezing meat. I immediately began to shiver. Perhaps that was why all these folks were so heavily clothed in an otherwise comfortable hospital. They were prepared for an arctic expedition after the surgery.

“Why so cold?” I asked.

“Keeps bacterial growth to a minimum,” came the response.

“Oh!” That made perfect sense in creepy way. I imagined bacteria growing on me in a warm operating room. Nobody wants bacterial growth. The last operating room I’d visited was cold, as well.

A blue-gowned man asked if I could help move off the gurney and position myself on the operating platform. I obliged and moved to an elevated platform where a padded clamp was affixed loosely around my head. “That’s the bucket,” I was informed. “Keeps you from moving during the procedure. Can’t have you move or you…”

“OK,” I cut him off. Didn’t really want to hear why he didn’t want me to move during eye surgery.

Another man came up to me and introduced himself as my anesthesiologist.

“Pleasure to meet you!” I said. It was. Anesthesiologists are my friends.

Vitals were taken and my blood pressure was as higher than it’s even been. 180 over something. A scary number in my mind. Mine is normally lower than normal. Figured, though.

“Blue coat syndrome,” I volunteered. “Never done this before.”

The anesthesiologist smiled and responded that he had something special just for that very condition. With that, he injected something into my IV line and soon the anxiety lifted. The blood pressure came down. I became chatty. Drugs…

My retinal surgeon appeared from a side door, Dr. Brinton. He was two weeks older than me and more than willing to explain anything to me that I might be curious about; always able to discuss the pros and cons. My kind of doctor.

“Good Morning!” I blurted out. He didn’t hear me.

A nurse soon came to ask if I wanted a warm blanket. I told her I did and she brought me two. Then she adjusted my head “bucket,” clamping my cranium into a soft but secure vice, and synched down my arms and legs with multiple Velcro straps. I wondered if I had mistakenly entered the interrogation room for hostile foreign agents by mistake. I was fully immobilized.

“To keep me from moving?” I had asked.

“Yes, that’s right.”

*

The longer the waves rolled in from the sea, the more I questioned where I was. I had no recollection of traveling to this beach. I was there by myself, apparently. The place was beautiful yet wholly unfamiliar. A desert island?

I wiggled my toes in the sand. The sand was warm, but it didn’t really feel so much like granular sand as it did the texture of a woven fabric.

What the heck?

*

Dr. Brinton wore a crown of lenses and lights on his adjustable, surgical headband. He approached, greeted me and asked if I had any questions. I did.

“How will my eye would be numbed for surgery? Will I feel anything?”

He responded, “An injection will be administered to the back of your eye, at the optic nerve. You won’t see or feel anything from that eye during the procedure.” My mind clambered around that concept, imagining the length of the needle required to place an injection at the very back of my eye. Inwardly, I winced.

“OK,” I replied. “What will that feel like?” I didn’t know when the “twilight” condition came about, or what it was. That was a term I kept hearing about.

“Well,” said Dr. Brinton, “the anesthesiologist will drop you fully under for the injection, then will bring you back to what we call “twilight.” In twilight, you’ll have enough awareness not to twitch or move around. Can’t have that. We will keep you there for the procedure. The other eye will be draped so you won’t see or feel anything.”

“OK,” I responded—still a bit confused.

Dr. Brinton finished the question and answers and moved away. Suddenly the side of my nose began to itch. It itched badly. I tried to outthink the itch, but to no avail.

“Excuse me,” I implored a nearby nurse. “I have an embarrassing request.”

The nurse looked at me with mild curiosity and a bit of annoyance. She was busy like everyone else in the room.

“I hate to ask you this, but could you possible itch the left side of my nose? I can’t do it.”

The nurse obliged and the itch stopped—another new experience, having someone else itch my nose.

Soon after, the anesthesiologist returned to my side and administered by knock-out cocktail through the IV line—and I was gone.

*

Still comfortably nestled in the beach sand, under the radiant sun, I heard the noise again. This time I recognized it as a human voice. A man’s voice. I listened closely and recognized a second voice. Two persons were talking. They were close.

“Blotter,” said the first voice in the form of a request.

“Thank you.”

As I focused on the sounds, the beach went away and I could see nothing but blackness. It suddenly became apparent that I might be in the twilight I’d been hearing about.

“Hello,” I said to the blackness. My voice sounded muffled.

“Hello, Steve,” came the response.

An answer, I thought. Interesting. “Am I in twilight?” I asked.

“Yes you are.”

“Fascinating,” I replied. “Are you working in my eye?”

“Yes we are,” came the response.” I recognized the voice of Dr. Brinton.

“Can’t feel anything,” I added.

“That’s good. Probably best you stay still and don’t do so much talking,” he said.

I thought about that: the idea that sharp metal instruments were in my eye while my jaw was flapping away. The wisdom of that request was suddenly clear.

“Roger that,” I responded.

How I could be in midstream eye surgery with awareness of mind and numbness of physical sensation blew my mind. I couldn’t even feel the pressure of anything against my cheek, which I assumed there was. Fantastic! Modern medicine was certainly pushing the thresholds of magic and miracles.

My brain then confronted the concept of what might happen if I moved or twitched with those sharp little tools in my eye if, for instance, I were to pay too much attention to the procedure or attempt to communicate further. Visions of gore permeated my imagination. It wasn’t nice.

“Enough,” I told myself. Chill out and go back to the beach.

*

Slowly, by the will of my sedated mind, the waves and sand came back to me.

Time to just enjoy this twilight business. Soak it in.

After all, what could be better than lying on a warm tropical beach in the surgical operating room?