Six of us encircled three drained pitchers of Larry Blake’s tap beer, elbow to elbow, eyeball to eyeball, down in the smoky rathskeller. We were grasping for a warm buzz on a winter’s night, seeking numbness, detachment, escape.

It had been a week—albeit, just another one—through which we’d been diligently studious, and subservient. A week that we’d hunched over books, inflamed our writing calluses, squinted at our calculators, while straining to understand, pushing to absorb, and cramming to comply. All the while we fought back the wild adrenaline-urges of bodies laced with far too much youthful energy. Week after week we’d followed the rules set by The Man. The Man—whoever he was: UC Davis in this instance. Maybe we were better for it. We complied so we might have a chance to grab that golden ring.

But now the week was over. Our goals and aspirations had been put aside; blunted for the evening. We were unleashed. That’s what we told ourselves. Yet we sat amid a throng of fellow students—comrade parolees—as if we’d somehow escaped our shackles. In fact, we hadn’t. We were still just as incarcerated; just removed to another arm of the grand penitentiary. And, our beer-numbing prison cell was increasingly grating.

When I returned to the table with two more pitchers, the group was pondering what to do with itself. Chris and Bob were in deep discussion, Guy, John and Tom looking on blankly. Ideas: some suspect, others wholly illegal, were being pitched. They were being chewed up. We were a think-tank in the beer tank.

What to do?

We’d climbed all the water towers repeatedly, hand-over-hand, up the exposed hundred-fifty metallic feet, clamoring around the locking grates that kept the riff-raff from the precipitous heights. Sitting up there on the rounded tanks, back to back, with the red strobe light flashing, often in a winter fog, under the right medication, was supernatural. But we’d done that ad nauseum. We’d even attached a huge F in front of the giant UCD lettering on the tank facing the highway; the one over the campus police station.

Frustrated, we considered moving to another venue, to the livelier Mr. B’s down the street. That was a short walk. The girls were generally more outgoing down there. We could probably plant ourselves at a comfortable booth. That idea was circulated and debated, but it soured. Mr. B’s wouldn’t do. Besides, we were now beyond girls. We were looking for a bold new adventure. Girls would have turned their backs—not for lack of originality, but in rejection of the risk. But we knew risk. That was our highest form of affliction and self-worth. Mr. B’s would be a step backward. Anyway, Mr. B’s management already caught on toour electrical-breaker-shutoff trick, so didn’t appreciate us there anymore.

Bob suggested we borrow the blinking caution signs he spotted near a Davis public works project. They’d fit nicely into Guy’s Super Nova. With them, we could block off the main intersection going to Woodland. The concept was run up the pole. We’d done that before. Maybe we could block off a freeway onramp. But it was just too easy and the predictable resulting traffic chaos had lost its comedic edge.

Too many stunts just sounded good but weren’t. One by one, concepts were vetoed. Chris described how we could light off a few sky rockets and M-80s on the Quad, just at midnight–in contravention of a recent University ban on pyrotechnics. Not a bad idea. But it wasn’t feasible. I’d recently run out of all my dynamite fuse that ensured our safe escape from the pyro-police.

More beer was poured.

Suddenly, out of one side of the collective hop-headed cluster came a roar. A minute passed before anyone could articulate the English language. Guy spit half a mouthful of brew across the table. Chris got a screwed up look on his face and motioned for everyone to quiet down. “We have an idea,” he said with a smirk. “A good one!” Then he began laughing again.

“Speak!” we all prodded in unison.

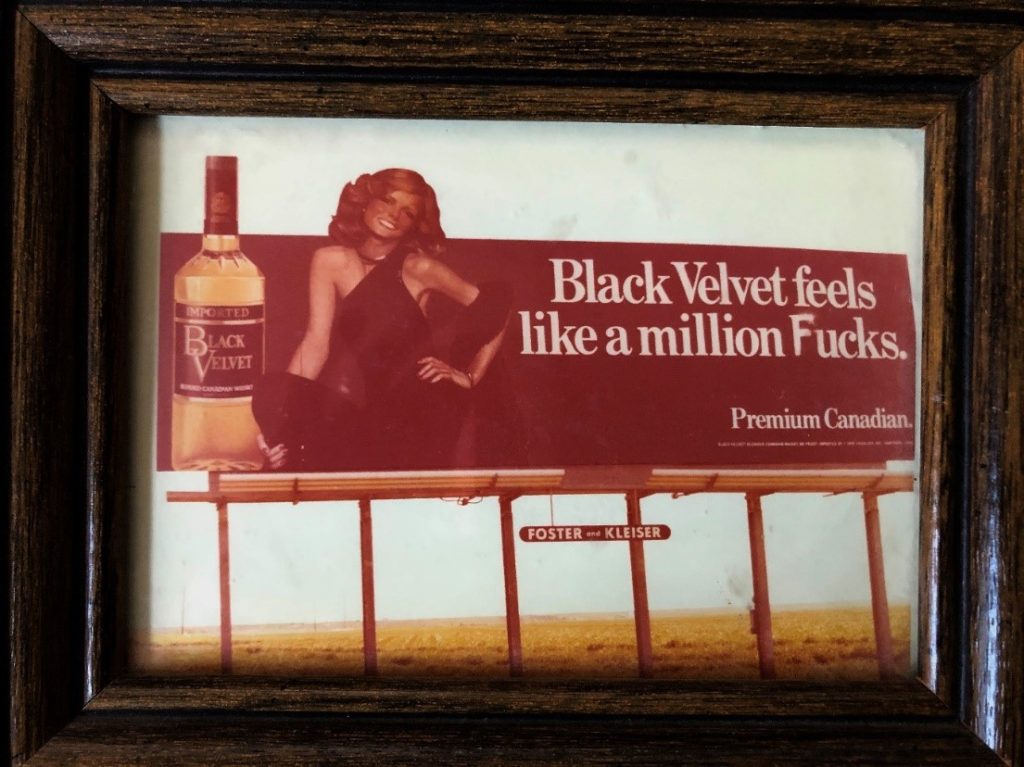

Gaining composure, Chris continued. It had to do with a big billboard on the freeway—one with the pretty face.

The billboard contained an advertisement with a bold message from The Man to the masses; but the theme was conflicted. There was a lie involved. The sign didn’t really say what it meant–so the message was transmuted, veiled in the name of profit. It needed to be corrected. Otherwise, the driving patronage might miss what was really being said. The Man’s sign needed to be made right. Maybe the Man might be corrected in the process.

“How high up is this thing?” I inquired. Clearly, highway billboards were up there.

“Well” responded Chris, “It’s high. It’s very high—probably extremely high. And there’s no ladder. But here’s the good news: it’s not illuminated. It sits out there in the dark.”

We all shared pensive glances.

*

Three cars raced from Larry Blake’s, through the darkened Davis streets, to different destinations. Everyone had directives. John and Tom went after ropes. Chris and Bob went for camouflage: dark shirts, caps, dark chalk for faces. We couldn’t risk some frontage road motorist seeing us and calling the officials. Guy and I sought out the art supplies. If the sign’s message were to be properly and legibly modified, we needed spray paints and customized stencils.

We then rendezvoused to plan the assault. The cars would have to be parked apart and a discrete distance from the target. We’d have to stay low, beneath the headlight beams of Highway 80 highway traffic. If someone drove along the frontage road, we’d have to go to ground not to be seen. We might have to stay face down in the fields for some time if the authorities arrived.

With agreement to the protocol, two loaded cars drove east, then exiting the highway near the Yolo levee. We spaced ourselves apart and dove calmly, authoritatively, with darkened faces, camo sweatshirts and black caps. Our vehicles were parked more than one-hundred yards apart and the lights promptly doused. We used penlights to unload the trunks and to find our way over the embankment to the weedy field surrounding the sign. Then, like Navy Seals, we slunk over to it, low to the ground, a surreptitious incoming human tide. That’s when we confronted the first obstacle.

“Shit!” stammered John, “that sucker’s high.”

It was. The planking below the billboard face was perhaps twenty feet up. It was dark too, so it loomed over us like some towering Sequoia. Six heads peered upwards in the damp night air.

John, our Goliath, took the rope. He carefully coiled it, swung it a couple times, and then hurled it upward toward the wooden platform. But he missed his mark–repeatedly. We needed it over the steel between the planking and the supports, so a climber could grab onto the superstructure. That was a narrow target in the darkness. After many attempts, he hooked it around the beam. But then the rope became caught, not going over so we couldn’t grab the other end, or pull it back down. It was a fifteen minutes before we got it removed and placed where we wanted it. Then the next obstacle presented itself.

One by one, each of us tried to shimmy up. Each would get five or ten feet up, dangling in the open air, feet flailing, then have to retreat back down. It was to no avail. Whether for our lack of circus training, or the beer, none of us could scale the rope. Six frustrated souls stood below the single dangling rope, rubbing abraded hands and cursing. The great yet-untouched sign stood its ground defiantly.

*

The billboard was supported by two huge I-beams planted vertically into the earth, which rose up beyond the height of the platform. Each was twenty-four inches or more in cross-section, from the top of the “I” to the bottom. I felt their rough weathered surfaces with my bare hands. The friction factor was good. It appeared one could somehow use the shape to counter-pressure upward—pulling and walking upward with little steps. If it could be done, it would be a committed endeavor. Once above ten feet, you couldn’t stop or falter—that could be fatal. You’d fall to the earth, back first.

I stepped forward.

Gripping the flanges of the beam closest to me, directly beneath the platform, I put my legs around so that my feet might walk up the inside of the opposite flanges. The traction was there. It seemed simple. As long as I pulled hard with my hands and pressed hard with my feet, I couldn’t fall. It was the wisdom that crazy Bill taught us up in the mountains–secure climbing was all counter-pressure. Always work the counter-pressure. If I could do this, Bill would be proud.

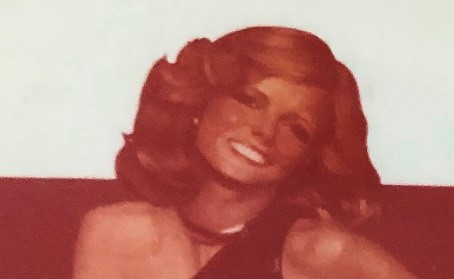

As my compatriots watched, I simply walked up the beam with little steps, hunched, horizontal, facing the sky, pulling with firm beam-ward counter-pressure. In moments I was up to the platform. There above me was the beautiful woman in black, faintly illuminated by the moving lights of the freeway. Panting, I looked down to the five heads below.

“How’d you do that?” stammered Guy, looking up.

“Not exactly sure,” I responded. “Maybe it was that last pitcher.”

From my vantage, the night-cloaked woman was huge. The board rose up another twenty feet to the top of her blonde head. The wording with the conflicted message was still a good ten feet above me. That was well beyond my reach, even on tiptoes. Damn. We needed a ladder. But we didn’t have one of those.

“Guy” I called down. “You have to come up. I have to stand on you.”

“Oh shit,” came a unified response from below.

The rope was repositioned next to the I-beam, and then slung over so Guy could be pulled up by the troops below. Somehow he got up in a huffing, sweating mass of Irish muscle. Then we were both there, teetering on the planks that seemingly floated in thin air just beneath the sign. It was best not to look down.

“Cops!” someone shouted. We promptly hit the wooden deck as the lights of a CHP on the frontage road momentarily lit up the entire billboard. I heard feet running and bodies splash to the ground in the big drainage ditch that had provided some cover in the field—it was full of water. Glad that wasn’t me; it was a sodden mess in those ditches. I turned my head sideways and upward to glimpse the woman in full light. She was beautiful—she was The Black Velvet girl. I’d seen her in the distance from the highway a million times. We were there to represent her, I thought to myself. We’d correct the lie, set the message straight.

When the lights passed, up came the spray paint and the paint shields in a bag tied to the rope.

We surveyed our tools, shook the paint cans, and inspected the single letter target above us, the one that required the careful edit. It was just one change. I stuck the tools in the pockets of my coat.

“How’re you getting me up there?” I asked Guy.

“On my shoulders” he responded.

“What will that put me above ground level?” I asked myself. “Thirty feet? More?”

“Steve needs another beer,” Guy called down to the crew below. “You’re probably going to die anyway,” he added.

“Yes,” I mumbled in agreement.

When the all-clear was sounded for frontage road traffic, Guy squatted down and I carefully stepped up onto his shoulders, one foot on each, hands against the surface of the billboard. Slowly the ex-football player rose to a standing position, hoisting me skyward. The letter, a capital “B” came into reach. Perfect. Now it just needed to be corrected.

“Guy, hold very still,” I ordered. It was more of a plea.

*

Undoubtedly most Highway 80 drivers viewed the Black Velvet girl as they would any unobtainable object in life—with desire. There she sat in her clingy black dress and pearls, next to the huge bottle of Whisky. Women might have seen her as a mere temptress. Perhaps they didn’t even notice her. As for the men, however, that message was different. It was simple. Drink this and she will be yours. That was the message.

But the written words didn’t say what the sign implied. It just said “BLACK VELVET FEELS LIKE A MILLION BUCKS.” What was a million bucks? No prospective purchaser of Black Velvet was interested in feeling like a million bucks, whatever that meant. If they’d seen the alluring image, then the girl was on their minds. The desire—and the intent of the sign maker—was entirely different from the phrase. It was conflicted. If the message was supposed to be so subtle as to be subliminal, it wasn’t.

*

So the sign got fixed. With a few quick sprays of the black and white paints, with shields placed to create new white and black borders where old ones had been, the foot-high capital “B” of the last word–one of the few words within the strained reach of our little human pyramid–was changed to a new, crisp capital “F.”

Now the sign said what it was meant to communicate. It spoke Black Velvet’s real truth. Let anyone argue otherwise. The freeway fanfare would not be fooled again.

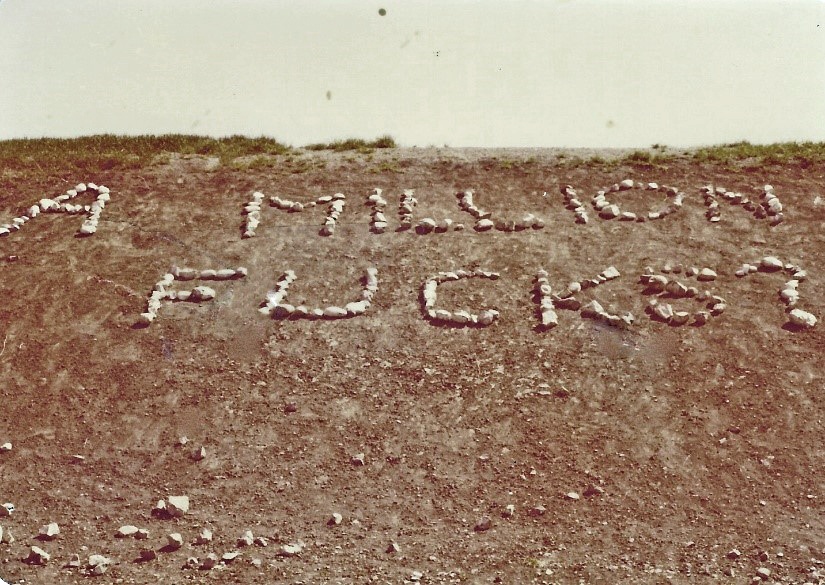

Just to alert drivers that what they had seen was not their imagination, we also “corrected” the rocks on the causeway levee that normally spelled out the letters of the Davis Greeks. The morning commuters took it all in—the sign and the reminder.

As reported and documented by Guy, trusty human scaffold and early riser, our work stopped eastward Sacramento-bound traffic the next morning. He rose before the sun, took his camera to the crime scene and documented everything.

There were comments and snickers all day on the Sacramento news channels, albeit cloaked so as not to reveal the exact nature of our “correction.” Guess The Man decided the lying jig was up on that advertising pitch.

As a coup de Grace, that sign was removed and changed to a wholly new advertisement later that same day—despite how easy it might have been to re-correct our little edit.