As we powered over the undulating washboard surface of the gravel track, the station wagon swayed and bounced like some decrepit trawler on a rolling sea. We were southwest of Tonopah, in a cloud of desert dust. Cynthia and I tried to play a shaky game of gin rummy on the back seat, while Mom pored over a book about Nevada ghost towns. Dad just drove on, robotically. There was grit everywhere. You could see it in the sun’s rays. It danced around on the insides of the windows.

When Dad finally slowed, I glanced up, hoping to see a nice, clean service station with a restroom. There weren’t many of those out there. That’s where we were, too—“out there”—west of the last ribbon of pavement between the California border and Death Valley; where “there” was just a lot of nothing.

With a lurch the car came to a stop in a gravelly parking area bordered by a few old rotting telephone poles and remnants of weeds scraped away by the blade of some state-owned bulldozer. It was another ghost town. Dad yanked on the brake, climbed out and released us for a general vehicular evacuation. An evacuation—that’s what I needed, too, and in a very bad way.

Out we piled, blinking in the desert light, squinting against the blowing sand and flying weed husks. The core of an old wooden mining town loomed in the near distance, connected to the parking area by a dirt path edged with little white rocks. That was our destination. Such towns were always our destination. A barely readable sign announced the municipality’s name under some official state insignia. Everything was weathered and cracked.

I wondered if there might be a state park restroom somewhere; one with a door, and a flushing toilet, and a lock, and a sink with soap. I craned my neck around but didn’t see one. There were just all those old buildings down the walk. My lower half cried for relief. This was shaping up to be another sorry moment in the wilderness.

*

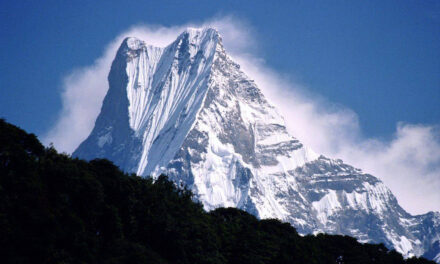

When Dad and I were backpacking, things were different. Up in the mountains, makeshift toilets could be discovered in nature or creatively fashioned with rocks and tree trunks. There was plenty of protective cover, thickets to walk behind—real privacy. We could search out a site, dig a hole and assemble a workable toilet to be used by our little community until it was time to leave. At departure, things would be buried, covered, and nature brought back to how it was.

Desert camping without an official restroom, however, was the worst. There was no cover, just rocks and tumbleweeds. The flat and treeless land offered no topographical protection. Privacy in that scenario usually meant getting distance from prospective onlookers—simple as that. Just walk a long way away: that, or just go public.

*

Despite the glaring sunshine, it was chilly in the desert wind. Dad handed out jackets, and Mom put on her walking shoes. Dad locked the car. Shoot! I bit my lip, knowing we’d be here for a while. Maybe a restroom would pop up–somewhere—behind one of the dilapidated buildings.

As we walked away from our transportation, my abdomen knotted. The proverbial comfort station might never materialize. I was loath to leave the car—the one piece of civilization, sole bastion of warmth and comfort, on this desert scape. I felt like retreating back to the stillness of its vinyl seats—to curl up and motionlessly wait for something better. But that wasn’t to be. Dad wouldn’t have it. There was no retreat.

Submitting to reality, my mind went into a state of focused diversion: into the desert-ghost-town drill, wherein I focused intently on the rustic scenery around me so as to shut out all other mental and physical distractions. Part of me wanted to confront my fear—in this case, a looming intestinal eruption—and just go; but that was the direct opposite of my need for privacy.

So I lulled myself into a state of educational wonderment, meditating that we were witnessing artifacts from our national past. How interesting! Just imagine living here back then. What would it have been like? I curled my mind around the stark, threadbare lives of the miners who lived there nearly a century ago. In the process, I tried to mentally isolate my lower half.

That didn’t help much.

Deep down, there was full awareness that I was deluding myself, distracting my growing strain. My bowels were moving unwillingly, unpredictably. My mental opposition had to be strong, or I’d lose it. I peered through a cracked window pane in a building whose wooden cladding was peeled and grooved. I gazed at bedsprings poking out of an old mattress, at the ripped pages of an old Sears catalog lying on the plank floor, at a rusty bedpan in the corner. Surely, someone should’ve come around long ago to collect these crazy old things.

I focused all my conscious discipline upon distraction.

In the next building, a table and chairs sat alone, forlorn, amid the dust and clutter of a kitchen whose plumbing had long since become inoperable. It appeared that nobody had used them for an eon. There were rodent droppings on the floor, and the cupboard doors were missing under the sink. As I stood looking in, the wind whistled around the corners of what used to be somebody’s comfortable desert home, now just a husk.

Stepping away from the window, my impending physical urgency took a new hold over my lower half—and my mind. The time was near. I had, perhaps, a few minutes. But there was no place to go. No gas station restroom, no state park toilet, nothing. Walking with a careful gait, I made my way over to Mom as she stared into another old building.

“Mom,” I began, “did you bring any … you know, “TP” from the car?”

Smiling, she reached into the pocket of her big, fuzzy camping coat and withdrew a half roll of toilet paper held together with a rubber band. She handed it to me.

Putting the paper into my coat pocket, I looked up and saw Dad eyeing me with a grin from the side of the trail. Guess he’d taken a pause from his historical perusing. It looked like he might be holding a rock in his hand. I glared back at him with a look that suggeted desistance and which considered certain retaliation.

*

Abdominal relief in the wilderness and aerial target practice went hand in hand among my circle of untrustworthy friends. Who started it, I’ll never know. Perhaps it was during one of our cattail wars in the Placerville countryside. Inevitably, someone dared to mix those apparently disparate activities.

Cattails, like javelins, could be accurately heaved far, and on predictable trajectories. They grew everywhere and were perfect for aerial bombardments, especially on brushy hillsides where one might otherwise find verdant camouflage from a pursuer. In a sense, they were organic mortars.

At some point, during a pitched mud ball battle amid the foothill scrub, a combatant had to relieve himself and thus called out for a momentary truce. The assailants, first voicing agreement but then seeing an opportunity—and despite the inability to actually see the preoccupied opponent–nevertheless took aim and hurled cattails in the direction of the pleading voice. High trajectory was everything. A cattail thrown aptly, would rain down like a spear, puncturing through any overhead protections. The eventual hit brought forth a hilarious release of curses and profanities, which amused all and sealed this bad habit forevermore.

Thereafter, whoever requested sanctuary for personal relief became an automatic target. The practice was perfected on backpacking trips in the high Sierra where rocks substituted for cattails. There, the eliminator typically took cover behind a barrier of boulders and tree falls, far away from the temptations of his companions—sneaking away. Seemingly, a long walk from camp was a safe tactic—but that very act was a temptation in its own right.

*

Sticking the toilet paper under one arm, I turned and stomped off, miserably contemplating my upcoming destiny, which might be ugly.

Keeping my breathing calm and regular, and walking with a short stride, I wandered away from my family, away from the parking lot, distancing myself from witnesses—especially Dad. It seemed wise to get a good distance from everything, particularly from the one individual who might take this as an opportunity for disruption.

Twice, I thought I’d walked far enough for complete privacy but I second-guessed those hasty decisions and walked even more.

Slinking behind one decrepit building after another, on a sad journey, I suddenly stopped and stared in utter disbelief. There stood a gnarled, wooden outhouse, one of those picture-perfect visions that some Nevada artist might have put into a painting of his ghostly mining town. It even had a door.

I stood there a moment, wondering if this was a protected antique like other historic buildings. A sign in the parking lot proclaimed that vandals and desecrators of California State property would be punished to the full extent of the law. What I contemplated might be deemed a defilement of sorts—at least in someone’s eyes. Sadly, I couldn’t be less concerned.

My body gurgled. I reached for the door.

The rusty hinges gave a loud creak when the door was pulled open. Inside was a wooden bench with a round, smoothed-over hole in the center. It was heaven-sent. There wasn’t much time to think, however, since the opportunity had been presented at such a critical moment. I scanned the dark recesses of the little structure for black widows but saw none. Good enough. I stepped inside, dropped my trousers and took a seat, allowing the door to swing shut with the slow creak of its tired hinges. I closed my eyes and slowly let some of the stress out of my lungs.

As my body proceeded to do what bodies do, albeit in the midst of that stark desert setting, I eventually sat up from my hunched repose, straightened and stretched my neck up with an inward grin. Having happily averted what could have turned into a horrendous nightmare, I mused at the likelihood that such a quaint little outhouse might have presented itself. Enveloped with that deeply relieved feeling that I’d “made it,” my face now facing skyward, I opened my eyes to what I knew would be a better day. There, not a foot above my face, was the head of a very large snake, hanging down from the wooden ceiling and staring at me. A forked tongue flicked from its mouth. I blinked. Then I blinked again.

*

Snakes were common in Placerville. They lived everywhere, feeding off the gophers and mice that populated the land. There were many types, too, in varying colors and sizes. Given our locale, only one snake was any real threat to one’s wellbeing—the rattler. Therefore, when encountering any serpent, there was only one real consideration: was it a rattler? If not, you just stepped over it and went on your way.

When we moved to the country and built our house among the oaks, we unknowingly created a snake haven on our back patio. During the hot summer there was something about its cool, shaded concrete surface that snakes just couldn’t resist. It was common to swing the screen door open on a warm day and face off with a long slithering reptile, staring us down with its black unblinking eyes. After the initial shock, we’d then try to identify it. If it wasn’t a rattler, it got nudged off the patio back into the weeds where it belonged.

My role as snake killer was typical among my country friends. On a sultry, still summer afternoon—we called that “snake weather” —I’d hear the call, though it might actually be in the form of a scream. That would be the cue to fetch a shovel. If the snake were poisonous, the shovel would separate the head from the body. If not, the handle would lift the serpent off the patio. No big deal.

Occasionally, a rattler got backed into a corner where it could protect itself from the shovel’s steel blade, and which provided it with a springboard for a longer strike. One had to size up the situation on a serpent-by-serpent basis. The thing about snakes was, you had to know what you were dealing with.

*

Frozen in disbelief in the little outhouse, my brain spun with every thought imaginable. My position was wholly vulnerable, my exposed neck in easy striking distance of the large serpent. My head swirled, flooded with questions.

Had the snake been there when I entered the outhouse? Were there more of them in there with me? Were its buddies directly below the hole over which I sat? Was this the last moment of my eleven-year-old life?

The suspended head, which continued to flick its tongue at me, was connected to a body that had the diamond pattern of a rattler. About one foot of the snake dangled from the ceiling in an S-shape, seemingly capable of lurching straight down in my direction. Another foot of the snake was coiled around a loose board hanging from the inside wall of the outhouse. The rest of it disappeared through a hole to the outside, where it couldn’t be seen. Thus the tail, with its potential rattles, was completely hidden.

My bodily functions made an abrupt switch to self-preservation, the blood flow redirected from abdomen to brain. The mystery of the snake’s identity was wholly unacceptable. Clear focus on its head, therefore, was critical. In the meantime, I dared not move.

As large as the animal was—its visible part the girth of my forearm—I knew it couldn’t really harm me if it was just a gopher snake. Those were good snakes, constrictors. They ate rattlers. It could bite me but I wouldn’t die.

So I sat there, and it hung directly above me, and the stare-off continued.

*

Dad and I were the first line of defense against our snaky Placerville infiltrators. Mom tried to do her bit, but she had an inherent resistance to the whole serpent topic; having grown up in the city where there were few or none—plus she just hated anything that slithered. To confuse things, some snakes, like the ever-present gopher snakes, had nearly the identical markings of rattlesnakes.

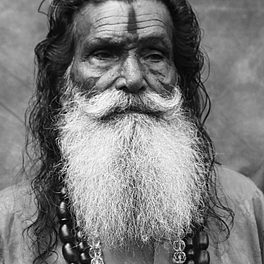

Rattlers had to be identified. The first item of note was the diamond pattern on their skins —that was easy, but not definitive since other snakes had similar patterns. You looked for the rattles too, although baby rattlers had few or none of those. The head shape was a different story, however. That was the real giveaway. You had to hold your suspicions in abeyance and analyze the head lest you eliminate a useful animal.

*

I continued to analyze the suspended snake, whose head—far larger than my clenched fist —just looked too sleek for a viper. The tail remained hidden. From its girth, the entire animal might have been five or six feet long. That wasn’t a nice thought.

In the darkness I still couldn’t quite tell if the eyes sat on a telltale triangular head. That was most troubling. Yet it hadn’t struck down toward the radiant warmth of my exposed head, so if it was a rattler, one worth its salt, then it was being rather lame about our little confrontation. A rattler should have done that immediately. That I hadn’t yet been bitten, and wasn’t now writhing in agony on the outhouse floor, was itself a telling fact.

So I decided it probably wasn’t a rattler—at least that’s what I persuaded myself in the shadowy realm of the little outhouse. All the while, it continued to defiantly flick its tongue just above my hair.

Seemingly the critter was just a big desert constrictor with good camouflage. And, I was too big to swallow and probably too challenging to strangle. Figuring there was nothing to do but ignore the whole darned thing, I lowered my head and continued my business. My personal needs had become paramount. Still, I covered my neck with my hands just in case it decided upon a gratuitous headlock.

I finished my business, not even looking up again. I’d pay the invading reptile no heed, lest I dignify its presence and embolden it. I sat for what seemed forever, a cold sweat beading around the upright hairs on the back of my scalp.

When I finally stepped out of the outhouse, I carefully walked its perimeter just to see what I’d been dealing with. On the back side, a huge snake dropped from the siding and quickly slithered away into a pile of old lumber. I caught a glimpse of its diamond pattern, but its tail and serpentine identity remained hidden beneath the weedy clutter. It was a monster.

Shrugging off the episode, I made my way back to the rest of the family, happy no rock-throwers had found me out. I was happy to be alive, and to be relieved of my urgent biological need. The day was now better, brighter. I wondered if the snake—during our brief visit—had been afraid of me.

(Wilderness House Literary Review 9/4)