Feeling hypothermic from an ice-cold shower—craving a full plate of urban cuisine after the trek—I pulled on a sweater and walked to a nearby cafe for some late-morning Nepalese sustenance. I hadn’t slept well. My back and feet ached, and my clothes were still damp from the bathroom sink washing followed by an ineffective overnight hang-drying within my rental cottage. I needed warmth, food, and a good light for reading and note-taking, things that had evaded me for weeks.

The cafe looked inviting. There were people inside talking and eating. Sunlight streamed through its windows, and hot omelets were advertised in a picture on the glass door. Perfect. I enthusiastically swung the door open, strode inside, and noticed the power was out. That stopped me. I stood there momentarily in indecision but remembered that all the other nearby restaurants I’d seen seemed far subpar compared to this one. So, this would have to do.

Selecting a chair in the sun, I sat down, figuring I’d at least have something better than the bland porridge I’d eaten nearly every morning on the trek for the last few weeks. The aromas of food and spices permeated the place. As I pondered how the outage might affect the kitchen, almost nearing a state of warmth, a traveler at an adjacent table looked over and volunteered, “Power’s off all over this end of town.”

“Thanks!” I’d responded, feeling more like saying, “Fuck you!” for the bad news.

My first day back to civilization was on one of Pokhara’s rotating electrical “off” days, the product of an ongoing power generation deficiency. Apparently, that had been happening for several years. So here, off the mountain trail, civilization still wasn’t so civilized. As I tried to keep from shivering, compelled to commence a methodical, mental rehash of the trek with my journals, the sunlight coming through the window snuffed out entirely. What?

I looked outside. Dark clouds were already gathering overhead, amassing for a mid-day drenching as central Nepal edged toward its spring monsoon. At least I had a solid roof over my head and proximity to food. And the extra gear I’d stowed at the guest house during the trek had neither been pilfered nor thrown out into a vacant lot. Things could be worse. The chill crept back over me.

The trek had been an overwhelming success, yet I felt off. My near-ruined clothes, expired travel visa, and mental state all needed to be gotten in order. I detested the feeling of being stationary, which seemed imprisoning and made me feel listless. I wanted to move toward a destination as I had for nearly three weeks—in clean and dry attire. But the spontaneous moving-on was now over.

“Patience,” I thought. That wasn’t something I’d been practicing. Marianique and I had practiced just the opposite. Each day, we barged off toward new places, engaging with new people, staying in new villages, and always striving to reach a particular distance. We never just sat for a day.

Buses, trains, flights, daily searches for accommodations, and constant social interludes would soon confront me. The thought left me feeling tired. Part of me wanted to hang out. Yet, the other part of me rejected that notion. It was always that way: two parts. I stared out the cafe window, convinced that the day’s passage might clarify things, that my laundry might dry, and that my visa might magically extend.

*

My return from the mountains had been one of those experiences from which I needed to space myself mentally.

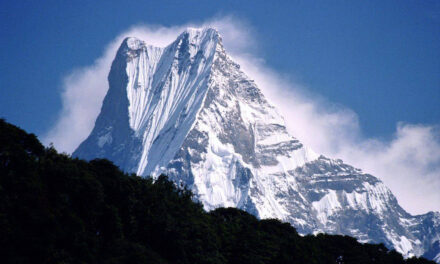

Marianique and I had taken a lesser trail off the Jomsom route from Gorapani, all for a bit of diversity on the way back. We were warned that there were Maoist kidnappers and robbers off the main routes and that we should be careful and stay together. That admonition rattled me, but we went anyway. The trail had proved to be a wet slog through miles of hale-covered mud, pushes through dripping eye-level ferns in cold ravines, then a plunge down switchbacks into a deep valley. As we descended in soggy shoes in the late afternoon, a great cloud had risen from the canyon below us and begun thundering. I had never looked down into a thunderhead.

We met the rising storm at the village of Gandrung and sprinted for the cover of buildings as lighting stuck around us and trees blew to the ground. We had to cover our heads from the large hail. The ferocious storm, more severe and dangerous than the deluge in Gorapani the night before, shook my sensitivities. By the time we sat down to eat, the ground was white.

The next day, we were beset by leeches during multiple crossings of the stream rushing down the valley from Annapurna Base Camp. The pesky, slippery bloodsuckers were a challenge to find, much less to remove from within our socks.

Then, a couple of days later, the abrupt parting with Martinique was awkward: too quick and far too casual. It left me with a sour taste. Not that we could ever effectively communicate–we couldn’t. It was just that our weeks of trekking had grown comfortable. On the day we might have walked out together, perhaps saying our farewells over a Chai on Pokhara, Martinique indicated—pantomimed really—that she would stay in the mountains, in Hille, and hang with the villagers.

I didn’t know what to say. But I did not want to linger up there—just the opposite, to move on—so I left her with a smile, a hug, and a cheerful wave. There were few words. We had no one to translate for us. We both knew our experience was over—or we should have. I knew. I wondered if the abrupt separation had somehow hurt her; or if it was something else. Or maybe I was hurt; I wasn’t sure.

Then, there was the feigned gratuity of the cute kid who befriended me on the trail down the last ridge. He directed me to a shortcut back to Pokhara, leading me while jabbing away, telling me he was going that way too, but then later demanded money for the advice. That bothered me the most. He fooled my supposed ability to detect scams, which I thought I could do after nine months on the road. He posed the simplest of scams—and I paid him. The kid made me feel stupid.

Finally, there was the storm during the walkout.

Big clouds rolled overhead the last three or four miles before town. After staying relatively dry the entire trek, the ensuing deluge somehow punctured through my innermost water barriers. Everything was soaked when I reached town. Rivulets poured from the bottom vents of the pack. Because I wasn’t quick enough to remove the mess of gear from my backpack, much of my clothing then mildewed.

The last day of the trek was supposed to provide some positive and endearing quality, even a bit of spiritual closure. Instead, I had perverted a goodbye, been scammed by the boy, and then been smitten by the weather. I felt like I’d been slapped in the face–if partly by my own hand. Nepal had given me some divine glimpses; now, it kicked me toward the exit door.

*

A blinding flash and cannon-like retort shook the cafe, rattling the hanging pictures on the walls, and the day changed from serene to foreboding and sinister. Lightning bolts came one after the other. Thunder volleyed after each flash, making a din that ruined the peace and drowned out the voices in the cafe. All heads looked up from conversations and food. No one could communicate.

Then came rain and hail–then, just the hail.

The little white balls grew in size. As in Ghorapani, they swelled to an inch in diameter. The battering sound on the tin roof was deafening.

Outside, leaves and small branches from the surrounding trees were stripped off and driven to the ground. The lawn in front of the restaurant quickly became a carpet of twigs, leaves, and flowers, all interlaced with white ice balls. When the storm finally stopped about an hour later, I was on my feet staring out the restaurant window in disbelief. Outside was another scene of destruction.

This was getting obnoxious.

With my journals in front of me, I reseated myself at a table facing a hanging mirror, with a window to one side and the customers to my back. Good for reading and writing where I could see in all directions. Then I ordered a pot of tea. Might as well catch myself up with a bit of compositional work; to re-adjust to an old routine. I was deep into the process when the restaurant door opened behind me, allowing in a cold breeze at my back. I looked up into the mirror. There was Doug in the reflection before me.

“No,” I thought.

Doug looked a bit neater than the crusty image he presented in the Kogbeni Red House Lodge. He spotted me, approached my table, and greeted me with a grin. I hadn’t seen him since that rather punitive night, so I was surprised by his sudden appearance. I politely motioned him to join me, which he did.

“Steve,” I reminded him—or maybe myself—in a mumble.

Despite his apparent cleanup, Doug still had a look that made me nervous. His plaid flannel shirt, worn blue jeans, and eroded running shoes were pedestrian enough. His expressionless face, which could be taken as a smile or a scowl, was neither; perhaps it was both. His hair, touching his shoulders, looked longer than at our last visit and screamed out for a hacking. But mostly, it was his eyes. They were engaging, yet withdrawn, while somewhere else–perhaps in another dimension.

Doug beckoned the kid waiter with a wave of his hand. He glanced at the menu, then ordered the mushroom omelets. That was the house specialty, as advertised on the sign painted on the door: an omelet on a plate, over which hovered skinny little mushrooms and magical sparkles. “Thanks,” I nodded, incredulous that he’d just selected and ordered my breakfast. He then cavalierly poured himself a cup of tea from my steeping pot.

Doug said little about the trek. Instead, he railed about the corruption of Nepalese city culture and the sad reality of the burgeoning construction for the tourist trade. It galled him. He raved about the mountains but missed much of the enlightenment I had witnessed. What he failed to mention was that evening in Kogbeni. Maybe the severe stoning of the California girl was of no consequence to him—not worth mentioning.

Politely, I reminded him about the hash ball and the obnoxious girl. It seemed an obtuse compliment that he’d appreciate. I shouldn’t have done that. Doug promptly retrieved the blob from his coat pocket. It was smaller now but looked as black and toxic as ever.

“Crap!” I thought to myself.

Doug began the familiar cajoling, and before I could resist, his pipe was loaded, lit, and in my hand. A curl of white smoke appeared and worked its way up to the darkened ceiling. I sat there in obliging disbelief, a victim of his mental strong-arming. Although we were in a public place, Doug was undaunted. He didn’t even look around to see who might be watching. But the waiter was watching–he came right over and seated himself at the table.

After that, the morning took a twist.

In fifteen minutes, the waiter was giggling. His eyes were red and watery, and he garbled his words. When he finally rose, he staggered away, muttering something about having to leave and being unable to wait on more tables. He disappeared out the front door, and I never saw him again.

With memories of the night in the Red House Lodge, I wondered if this devolution of mind was a smart move. It probably wasn’t. But what was done was done. I had sucked in two hits. The day’s die was cast.

Shortly after I finished eating, Doug rose, put money on the table, and then excused himself, whispering, “See-ya round, enjoy the magic!” Then, like a vapor, he disappeared. Relieved that this ghost from Kogbeni was now gone, I suddenly froze. Raising my eyes off the table, adjusting my glasses to focus on the glass door with the painted picture, I suddenly realized that the “magic “reference had to do with the mushroom omelets. It was those things floating over the plate. That’s what the café made–magic mushroom omelets.

“Yikes,” I muttered.

*

I remained seated at my café table as if rooted. It was safe. As a heavy wave of THC washed over me, I planted my feet securely, one on each side of the chair. I would weather this new storm. My supplementing and completing of journal entries might have to wait.

“Mister?” said a little voice.

A little person stood beside me – a young girl. I hadn’t noticed her come in. I smiled and pushed away my empty plate. Apparently, she’d quietly slunk into the cafe to talk with me. I gave her my attention.

The girl might have been eleven or twelve, certainly no older. Her little face was painted with garish makeup; red lipstick and rouge haphazardly applied. She wore a tight-fitting skirt and had red toenails. I was amused but also appalled.

Staring at me, smiling, she spoke in broken English. She asked, “Mister, you want?”

“What?” I asked, not getting her drift.

She stood before me like a little statue with a forced smile. Then she walked over and put her little pre-adolescent hand on my arm.

I was speechless. “What…? I began.

A new waiter walked over to the table and, appearing to know the girl, cleared up the misunderstanding. He explained that she was soliciting me–that’s all. She would go with me; for money. I could do with her whatever I wanted.

The girl smiled at me as if to say, “Yeah, what he said.”

I looked at her. She hardly looked old enough to understand what she was asking for. Her face was that of a child. She was just a kid.

“No!” I stammered politely and softly. Then, “No, thank you.” I smiled back, having difficulty looking directly into her eyes. She was, after all, merely a giant toddler.

When she didn’t immediately depart, I waved her away.

“Go! Please.”

As she turned to leave, I had to blink to be sure this wasn’t some hash-induced hallucination. I looked out the window and then back. Her hands were half the size of mine, maybe less. She wasn’t even old enough for acne. What the hell was going on?

The girl didn’t look hurt by my rejection. She wandered over to the table of the only other group of male tourists in the cafe. I was relieved when that group of four German trekkers also brushed her away. They were more abrupt about it. That was okay. Happily, our collective semblance of Western morality had taken a stand.

Finding no willing takers, the girl walked out the front door, looking for other opportunities. I wondered where she lived and who her parents were. Was she an orphan? Had she been explicitly directed to solicit Westerners? Had any of them taken her up? Well, fuck them if they did, I thought.

As I was pondering the child prostitute, the next assault came from behind me.

*

A radio that had been playing melodic Indian music suddenly elevated to an obnoxious volume. But for the cold and unfriendly weather, I would have walked out after the experience with the young girl. Instead, I’d stayed in my seat and tried to get back into my writing. But the radio–a small boom box–wouldn’t allow it.

I turned in my chair to face my tormentors, a young couple. The girl looked Indian, perhaps seventeen. She wore a sari and had one of those red dots on her forehead. Her partner, a westerner, appeared to be in his mid-twenties. He wore jeans and tennis shoes and seemed more interested in what he was reading than in her attention. He looked European.

The girl fawned over him. She re-tuned the music to Western rock so she could loudly whistle along in a tone-deaf attempt at cross-cultural adoration. It was ridiculous. She didn’t know the songs and couldn’t follow the melodies. When her Euro-man ignored her, she whistled louder.

It struck me that this was a symbolic demonstration of how the West regards, seduces, and corrupts the have-not cultures of the world. Neither of the two noticed me staring at them. I wondered if this girl was another solicitress.

That was enough.

I arose from my table, left money next to my tea, and vacated the premises.

Stepping into the storm-thrashed street, I fell into an emotional funk. Everywhere I turned, there was some cultural undermining of the Nepalese people to whom I’d grown so fond. During the eighteen days I’d been on the trail, a new guesthouse and restaurant had been completed around the corner from my cottage. Pokhara was abuzz. Western music blared in the streets, hammers pounded, rich western trekkers bartered for everything, and drugs laced the entrées. It was a culture’s rapid erosion, and there was nothing anyone would ever do about it.

*

On the verge of ranting to some hapless passerby, I caught myself, thought twice, then stomped back to my rented abode and retrieved my to-do list. It was time to concentrate on taking control of my world–at least for the rest of the day; time to focus on my reality. By then, I‘d forgotten about Doug, what he’d done to my head, and what I’d eaten. The hashish was manageable, but “breakfast” hadn’t yet taken effect.

To be purposeful, I listed several simple tasks: hunting down batteries for my flashlight, investigating the Kathmandu bus schedules, and purchasing snacks for the room. Then, I remembered my expired visa. I opened the city map and realized I was only two or three blocks away from Nepalese Immigration, where I could pop in for a visa extension. By extending, I could prolong my stay in Nepal. If extended, I could leave Nepal without having to turn in my trekking permit, a souvenir I wanted to keep. I looked at my watch. There was just enough time before business hours ended if I hustled.

Full of purpose and adrenaline, I stepped out, locked up the cottage, and strode off, map in hand. Caught up in the joy of something meaningful to do, something I could accomplish that day, I didn’t think more about it.

On my new mission, I located the Immigration office, walked in, filled out a form, and submitted my paperwork to the official at the window. There was no line. Five minutes, I figured. Easy. Before I could contemplate what I had set myself up for, I was called by name by an armed man in uniform, beckoned, then officiously escorted past the front counter and down a hallway, through a door, and seated before a Nepalese official and his armed deputy in a small room with bright lights.

“Huh?” I thought.

Then it hit me. Holy Crap! The mushrooms. I shouldn’t be here. What have I done? I looked at my watch. It had been about an hour since I ingested the omelet at the café. Then I thought about my expired visa. In many countries, an expired visa is a violation of the law. A bad feeling crept over me.

*

The stillness of the Immigration office made me realize how strongly I was still reeling from the hash ball. My mind was racing. Worse, the mushrooms were starting their unpredictable escalation. I could feel them coming on. I tensed up, panicking that I might reek of the hash. These officials certainly knew that smell–there were stoned Westerners everywhere. Had I brushed my teeth in my haste? I couldn’t remember. My short-term memory was already looped. I might as well have floated in like some magician’s levitation trick to a rapt and suspicious audience. The bright lights and echoes in the stark office brought that realization home.

The real question was whether I could escape before the mushrooms pummeled me into oblivion. Of course, there was no way to know how many were in the omelet. I had to control the situation. I remembered Abdul and his asshole brothers in Morocco. That escape could never be pulled off here. These guys had guns.

Sadly, it was too late to retreat–which might have revealed that I was paranoid, a big red flag. One can’t act paranoid with Immigration officers. So, I sat tight in my chair, glad I was still wearing my darkened photo-grey prescriptions. The fluorescent lights would keep them dark enough to mask the redness of my eyes and bar any glimpse into my increasingly freaked-out soul. I told myself that my paranoia was derived not from reality but from my drugged imagination–so far, anyway. I just needed to maintain an air of confidence. In any event, these officials were still clueless. I reminded myself that their perception–my demeanor–was their reality. I felt my shirt collar to be sure it wasn’t twisted under and ran my hand down my shirt buttons to be sure I wasn’t looking like an indigent.

This had to be an exercise in mental discipline. I’d have to peremptorily monitor the content of all that might spew from my mouth—before it came out. It would be a covert, straight-faced, check-and-balance operation. Stay calm, I thought, or you’re fucked.

The official in charge leaned forward in his chair and began reading the form I’d just filled out. As he did, two other uniformed officers entered the office to participate. I was then drilled with questions under the stares of the four men. All wore side arms. None seemed particularly charmed by my Western presence.

I had expected a slow-moving, bespectacled administrator behind a counter who might disinterestedly sign off on my extension without many questions–like a driver’s license extension at the DMV. This looked more like a military interrogation.

The head official boomed, “You are twenty-six?”

“Mm…Yes,” I muttered back through a mouthful of cotton. His tone rattled me.

I looked around for a glass of water, but there was none. It didn’t seem prudent to ask for one.

“You have been trekking for how many days?”

“Eighteen,” I answered.

I was then asked to show my passport and trekking permit, which were scrutinized closely by all the men. Then ensued all manner of questions concerning where I got the visa, why it wasn’t obtained in the US, why I was in Nepal, and so on. I kept my answers brief and to the point, my expression pleasant. All the time, the mushrooms were sending distracting pulses through my freaked-out brain and quivering body. There were questions about where I’d been. Why had I gone to Israel? What had I done in Pakistan? Was I in the business of traveling?

I got the impression that the head guy wasn’t buying some part of my story and that he might just be disinclined to extend my visa. My case was sinking. By now, the mushrooms were pushing me beyond the edge of paranoia. One part of me reveled in how I might cleverly extricate myself from this most challenging situation; another prayed for a hot air balloon back to Kansas; a third part fought the urge to howl hysterically. “Get me out of here!” resonated in my head.

All the officers had scowls on their faces. Would they eventually grow large teeth and alligator tails? Was the one in the back of the room looking at me suspiciously? Had I said something wrong or offensive? Did the king’s portrait on the wall just wink? My mind did cartwheels. The questioning went on and on.

Then, the head official took a different path, lacking relevance to much of anything.

“You are from Cal-y-for-na?” he asked, looking at my passport photo page through his thick lenses, carefully putting syllables together.

I wondered when this would end, daring not to look down at my watch again.

“Yes, Northern California,” I responded slowly.

Two of the guards looked at each other and one nodded. They had been pointing at something in my passport as the group had questioned me. Was there an issue with where I was from, not where I had been?

“Ca-lee-far-nee-a,” pronounced one of the guards to the other. The other one smiled.

Perhaps they were messing with me.

New questions kept coming, addressing where I went to school, the identity of my family, and why I was alone. The predictability of a simple visa extension seemed to be mutating into an unbridled interrogation. I had no idea what was happening. My stress level was increasing, which accelerated the effects of the mushrooms. I wondered if my facial expressions were regular, or if I was twitching, or perhaps drooling. My feet grew sweaty, sliding in mud puddles in my dirty flip-flops.

“You are doing more trekking?” came a critical question. The officials were comparing the dates on all my documents. There was little time to accomplish another trek, but it rationalized the reason for the extension I sought. Not that I was planning another one. I just wanted to hang out longer in Nepal.

They asked why I hadn’t come in to extend sooner.

I responded, “I was sick.” I had been–just not in Nepal.

I waited for someone to object to my irrelevant and evasive response.

“What was the matter with you?” the head official inquired.

“Well,” I responded slowly, thinking what to say. “It wasn’t dysentery.” That was true, at least in one instance. I stayed silent.

“Did you see a doctor?”

“I am on my way—after this,” I lied.

They all just looked at me, again at my documents, then back at me again.

Their stares were harsh and judgmental.

Then, out of the blue, one of the guards asked if McGarrett lived in California.

“What?” I responded.

“McGarrett,” he repeated. “Hawaii Five-O”

“Uh… No,” I said. “What the fuck?” I thought.

“Oh,” he muttered, looking puzzled, somewhat annoyed.

“He lives in Hawaii,” I volunteered. “At the beach.” I had no idea if that was true.

“California has beaches, too,” I added.

“Oh!” he exclaimed. “Beeeches.” He paused and whispered something to the officer next to him. “California has girls?” he continued, “Like Hawaii girls?”

I just looked at him. My brain raced in survival mode. This was ridiculous.

They all looked at me as if this was a pivotal question. If not, it was undoubtedly the most exciting subject they had reflected upon that day. Then, the drug-laced wheels turned mysteriously inside me.

“Oh, yes,” I stammered. “California girls are all like Hawaiian girls.”

The guards smiled.

“Yes. They are blondes. All blondes in California,” I continued. “And they surf and wear bikinis.”

I reached down and wiped my perspiring hands on my bare legs, not knowing what I might say next. I was losing it and felt like ranting or laughing out loud, but the situation was too crazy for that. When my racing mind admonished itself to “Use the force, Luke!” in the voice of Obie Wan, I nearly burst. But I didn’t–I couldn’t. And I’d not be sharing that vision with my tormentors.

Between questions, I kept silent. At any moment I expected to be manacled and removed to some dimly lit cell for bad westerners.

“These girls; do they like to—you know?” the guard said, staring at me with a curious but serious look while making a sexual gesture with his body.

I stared back at him in disbelief—into his shallow yet inquisitive eyes. My creative light suddenly glowed brighter. These people believed all they’d seen on American programming, including all the crap and all it insinuated. To them, Hawaii Five-O was America. Hawaiian girls were Californian girls. Why not?

So, I carefully responded, “Yes! Yes, they do that–all the time. Mostly with surfers like me.”

The guards exchanged wide-eyed, knowing glances and then laughed aloud. “You’re a surfer?”

“Yes. In Malibu!” I emphasized.

“No!” responded the inquisitors together.

“California is like that–for you?” the one guard asked in more of a lament.

“Oh yes, for me–all the time. Me and McGarrett,” I stated with conviction.

With that, all my tormentors trans-morphed into adoring fans, beaming joyously at me, and I realized that I’d somehow become elevated from a typical western, lowbrow trekker to a McGarrett-style lady-killer of beach girls. And that was a good thing.

One of the quieter guards reached over and patted me on the shoulder. As laughter suddenly permeated and disrupted the hostility of the room, my visa was stamped and signed with all the necessary extensions.

The process was over.

Before I left, each guard shook my hand and congratulated me. I bit my tongue. Ironically, I was thankful for their corruption by American television. The culture I was so recently condemning, which included the warped image factories of Hollywood, had thrown me a life buoy.

*

Back on the street, out of the interrogation room, all I could contemplate was hurrying back to my little cottage with the hanging laundry. I needed to avoid humankind until the morning’s omelet let go of me. So that’s what I did–immediately.

When I arrived back, the cottage was still damp, but quiet, secure, and safe from the likes of my day’s various acquaintances. I locked the door to bar the likes of Doug, child prostitutes, and immigration agents and sat on the bed. It was time to regroup in a big way. The sound of wet clothes dripping onto the floor soothed me.

Finally, I rose and walked into the bathroom. No true rejuvenation would be complete without sticking my face under the cold water and scrubbing away the dried sweat and the lingering taste of Doug’s little hash ball from my teeth. Having done so, I stood and faced myself in front of the cracked mirror.

I stared at my dingy flannel shirt, worn blue jeans, and faded running shoes. They were clothes from home and worn almost daily for months. My hair was getting long, too, shoulder-length, near the time for another session with the scissors. My eyes appeared distressed and distant, and I was uncomfortable looking at them, so I looked away from my image and loaded my toothbrush for a third-world, waterless brushing. Simple tasks like tooth brushing simultaneously aided in my mental and physical regrouping.

My cottage fronted a tropical garden where water buffalo came daily to nip the blooms off the vines. From the garden, you could see a few of the Himalayan peaks. My little bathroom window faced into a flower-infested side corridor leading from the garden to the dirt road out front. All the windows looked into little jungles adorned with spring colors.

Not needing the sink while scrubbing my teeth, I swung around to gaze out the bathroom window. The tiny space cocooned me safely, like a womb, while enabling me to visually connect to the garden. I stood there for several minutes, still tripping but lost in the beauty. That’s when I noticed something large in the foreground that blurred my vision.

I pulled my face back from the screen and refocused. The blur was a dark spider sunning itself on the screen. But it wasn’t just a little garden spider. It was the size of my hand. It had strong-looking, hairy, tarantula-like legs but looked sleek and fast. If it was a garden spider, it was a Godzilla version. It had bold markings, too, and its abdomen was the size of my thumb. The way it clung to the screen, taut like a stretched rubber band, made it appear agile, capable of quick movements.

“Shit!” I said out loud. “Glad your nasty ass is on the outside.”

Then, I stopped brushing and swallowing my toothpaste with a gulp. Something was odd. Part of me was entranced, having never seen a spider quite that large except in a zoo. It looked dangerous, but there was a screen—thank god! I was not friends with big spiders. My heart raced despite the barrier.

Curious, I moved closer to inspect it, moving my face toward its body. As I leaned in, it tensed as if it were aware of me. I sensed it would jump, so I stopped moving, my nose about six inches from the creature.

Momentarily confused by what part of the spider I was viewing, I suddenly realized I was looking at its back, not its underside. It was on my side of the screen. My heart slammed inside my chest.

Holy crap! I said nothing, not wanting to even breathe in its direction.

The colossal arachnid was clearly being crowded, and I was the invader. I envisioned it jumping onto my neck, injecting me with venom, leaving me twitching on the bathroom floor while it summoned forth its spider friends. My reaction was to recoil backward, but my legs wouldn’t move.

The thing was too large to kill by the usual means, and no substantial spider weapons were within my reach. And if I missed killing it and made it mad–I didn’t want to think about that. The bathroom walls made for close quarters. I’d never outmaneuver a fast arachnid amid the corners and cracks in the tile floor and wooden walls.

Instead, I backed away very slowly.

Taking deep, moderated breaths, I retreated with as few jerky motions as possible. I didn’t exhale in its direction. My eyes never left its threatening form.

As I backed away, I quietly grabbed my shaving kit, towel, and other hygienic items with a gentle sweeping motion of one arm. The other arm stayed near my face and neck, ready in case I had to repel a frontal attack. All the items on the windowsill below the creature were left in place. Those could be replaced. Then, I backed out of the bathroom and gently closed the door.

Back in the main room, I speedily gathered drying towels and other items that were not indispensable and stuffed them around the bathroom door. I sealed it so that nothing could invade the room from that direction. That done, I scouted around. There were no other spiders, but there were cracks and potential entry holes into the room everywhere. Imagining what might lurk within the walls, I sealed off all the larger voids.

Finally, I walked outside to peer back in the bathroom window; needing to verify the position of my nightmare come-to-life. But when I looked at the screen where the creature had been, the spider was gone. And the screen lacked any holes large enough for it to have crawled through in the first place–so it was still in the bathroom. It had to be.

That was enough. The whole day was enough.

*

I could have asked the guest house management to provide another room. I could have gone somewhere else. But I didn’t. Why reveal my revulsion for big spiders? They were probably all over the place. So, I stayed put and kept the experience to myself.

Instead, I spent the evening back at the omelet cafe trying to stabilize and be constructive. Determined as I’d been to scorn decadence and maintain a clear-minded first day back, I’d failed–miserably. I’d come full circle and was now captive in the place where it all began. Rereading pages over and over, it became clear the mushrooms were still playing havoc inside my head. That damned Doug, I thought. This special day, the first day back from the long trail, was one bad joke—many jokes, like the day before, one after the other.

Staring out the café window, I realized how ironic this had become. I’d escaped my American life to see new cultures, on a free-thinking solo quest outside “the box.” Facing discomfort, confrontation, and paradox, I’d grown less judgmental about some things. People were different, and they thought differently, and that was okay. But I’d grown more judgmental about other things: the living conditions for children, the masses of poor, the lack of adequate construction and sanitation, and the way the West seeded these cultures with its materialistic poisons. Not that the Nepalese needed many material things–I witnessed that fact.

But it was the eagerness of foreign profit centers—McDonald’s, Baskin Robbins, even Pepsi—to insert themselves, as if through intravenous drip lines. The poor cultures presented their exposed veins to the drip while letting the real problems persist. And then, the new addicts became desperate for more money to support their habit. They would do anything for American dollars. And we tourists just walked about blithely, drinking the tourist punch and taking pictures.

Yet I’d not forgotten my moment on Poon Hill or the other messages the trek presented. That was in me forever. But I had to laugh. Now that the message was delivered and the ethereal ceremony was over, the same omnipresent force had seemingly given me a new message. I imagined it now, boomed down forcefully from the heavens: “Okay, western asshole, you’ve had your damned epiphany already. Now get the hell out of here before you fuck things up even more.”

*

Long after dark, I returned to the cottage and pushed the wood-framed bed far from the bathroom door. I removed everything from the floor that might facilitate something crawling up to the mattress. Then I read late, keeping my candle burning and my eyes peeled for long, hairy legs. It was an anxious night of fits and starts in which I dreamed about dripping clothes, giant spiders, and Nepalese immigration officers.

I packed my things the next day and boarded the bus back to Katmandu.

Wow… I’ve been there, for sure… I think “we all” have… Drugs or no drugs, being far far from home brings us situations we never imagined, never would have signed up for. And we — brought up to think of ourselves as at least capable, which we have, after all, demonstrated by maneuvering ourselves halfway around the planet — right? — we tend to blame the new place, the new culture for all our “problems.”

It’s ironic how one of the things that drives us to go traveling (the desire to break out of all the familiar and routine stuff at home and to have new experiences) eventually drives us to a new levels of appreciation and longing for the comfort and safety of our old familiar routines. Get me outta here! I wanna go home!

Enjoyed it, Steve — read it from start to finish.

Did I ever mention to you the excellent book “Tripping”? it came to mind while I was reading your piece. It’s a wide-ranging collection of first-person psychedelic experiences., covering the whole spectrum between extreme joy and profound insight to utter terror and what seems like certain doom. I think I owe it another read.

https://www.amazon.com/Tripping-Anthology-True-Life-Psychedelic-Adventures/dp/0140195742/ref=sr_1_3?crid=TNXXHHUNC2EH&keywords=tripping+terence+mckenna&qid=1701638651&sprefix=tripping+terrance+mckenna%2Caps%2C127&sr=8-3