Marianique and I reversed course and headed back down the mountain from Muktinath, a depressing venture. Neither of us wanted to retreat from this high part of the world. We wanted to go farther. We were so close to the mountain crags, so far above tree level. It seemed that all the elevation gains and acclimatization were for naught—all the friendly mountain folk barely experienced.

As if to further squash our inclinations and push us back, great cold clouds rolled in from the Indian lowlands, worsening each day. They looked beautiful and harmless on the approach yet breathed out snow, lightning, and hypothermic gusts. Mornings were crisp and clear, but by noon, we were looking upward and wondering what we were in for.

Afternoon temperatures dropped from comfortable to freezing in an instant. We rationalized that our departure was necessary. I did, anyway. Presumably, Marianique did too. Our rain covers were meager and our cold weather gear sparce. Once back along the Cali Gandaki River, we did our best to avoid further deep fords.

The trip downhill was on hardened muscles. We moved with momentum, in long strides, back along the Jomsom trail with the gritty surface winds now pushing us from behind, back past all the prayer wheels we’d spun on the way in. It was more than four days since I’d washed my hair, nearly a week since I’d partly submerged in the river during our big ford. I felt, and probably looked, as filthy as the local kids with the dirty faces and runny noses.

Still, I was healthy—Marianique was too. During the trek, I had only drunk hot tea from boiling caldrons that I had inspected and then paid to have poured into my thermos. I had not eaten the curd, which was not pasteurized, and had stayed away from the Chhaang homebrew that many travelers raved about. Many of those other travelers were ailing. Those precautions seemed like small sacrifices.

As the daily storms gained ferocity, new snow dusted the lower shoulders of the peaks behind us. Afternoon thunder exploded over our heads, enhancing our sense of urgency. The season was changing to an extreme we likely didn’t comprehend.

*

The downhill walk, which became more of a sprint, was all about not twisting ankles. That took focus when pushing a four-mile-an-hour pace over the rocky scarp. Fortunately, our feet were now hardened and blister-proof. In one day, we walked all the way back to Marpha. I craved a piece of apple pie, but, as such things went, Marpha was out.

The descent out of the highlands became treacherous. Parts of the route that we had obliviously plodded up—often leaning forward over rocky steps—snaked over thousand-foot cliffs that we now directly faced. It was a game of not looking out at the view while you walked, carefully minding the next step: descend, stop to look, descend more—never simultaneously—and keeping your hands ready in case you slipped. Eventually, we dropped back into forests of pines, then stands of bamboo and occasional wild marijuana plants. Piece by piece, we stripped off our cold-weather clothes and stuffed them into our packs.

Three days out of Muktinath, we walked back into the riverside village of Tatopani. This time, compared to where we’d been, the place seemed like a busy resort. Young travelers from France, Germany, Switzerland, Canada, and the US were in temporary residence. The chatter level was loud in the village, especially around the thermal pool, whose waters looked as questionable and unrefreshing as they had more than a week before. Everyone was out basking in the heat and lolling in the water. Among the trekkers were all sorts: hippies, the strait-laced, a few climbers, and even a German follower of the Bhagwan dressed in red. It seemed eclectic for a mountain hangout. It felt nice after over a week of plodding in the cold and dust.

Loud, soft-looking arrivals who would go no further uphill were apparent, too, with their clean clothes and sparkling faces. We discovered some had been hanging out there for days, sipping Chhaang, blithely chattering, and watching everyone else troop by. They seemed out of place and needed to be put back where they belonged: Fort Lauderdale, Phuket, or Cancun. The rest of us were dirty, chapped, sunburned, worn, and desperately needed a bath—two factions of trekkers. I avoided the scene and tried to wash up a bit in a nearby stream.

*

There had seemed to be no time to dawdle on the upward hike, but the downward course differed. We were drifting back from the higher ground, yearning to socialize just a bit, not toiling as hard, our respective destination goals having been met. During the afternoon, I slowly befriended a group of grubby returning trekkers like us.

There, I had the chance to sit down with fellow American Brad Newsham and his wife, Beverly, whom we had met on the trail and shared a Chai or two in several villages. Brad was an aspiring writer full of travel tales who had drifted all over Afghanistan some eight or nine years before. His travel pursuits inspired me. No doubt, there were many fascinating stories floating around Tatopani and I wanted to hear them all.

After dinner, our little group sat on the lodge’s porch with Brad and his wife and sipped Chai. Marianique wandered off to chatter with some French speakers. I pulled out my hash ball and pipe, and we eventually attracted even more travelers, including the Bhagwani. Conversation lines drifted. The pipe went round and round. Soon, the Bhagwan was spilling forth his views about Krishna, Vishnu, and other Indian ideologies. Travel stories, including thoughts on politics and religion, were shared among young faces who wanted to hear diversity from their fellow earthlings more than they wanted to judge them. The evening with the trekkers, next to the river and under the star-lit peaks, became magical.

Later that evening, a very red-eyed Brad leaned across the table and shared a private story with me in a lowered voice. On his way toward Muktinath, but while in Tatopani—near where we now sat—he had awoken one night, unable to sleep. He arose, leaving his wife to sleep, wandered out of their lodge, and found himself next to the thermal pool. (Brad thought that rocky chum bucket was delightful and couldn’t get enough of it.) He was alone and in a fitful mood of Western fretting over career choices, life, and other things. So, he decided to take a nighttime solo dip in the warm waters.

Brad elaborated on the joy of his midnight soaking: the water’s warmth in the cold air, the silence, the stars above, the high snowpacks illuminated by the night sky, and the marinating heat that melted his troubles away. However, as his eyes became more accustomed to the dark, he realized that the nearby rock walls, trees, and bushes around the pool were all cloaked with drying laundry—a rather horrid sight to behold in that euphoric setting. Brad spun around in the waters in disgust, wondering where those things had been washed. The pool?

As Brad’s euphoric state plummeted back toward the funk that brought him to the pool in the middle of the night, he inadvertently placed his foot on a soft, soggy piece of something on the rocky bottom. The squishy feeling against his toes was immediately revolting. He grabbed the object and yanked it to the surface. “Some big old tunic thing, made out of burlap or something,” he told me. He held it up and then wrung it out.

Brad went on about the experience: “I really don’t give a damn what you wear—you wanna wear draperies, that’s your business—but can’t you at least keep them out of my goddamned hot tub?” He took the piece of material, whatever it was, and draped it over one of the bushes next to the other laundry items. He then returned to bed and slept soundly for the rest of the night.

The following day, Brad arose to a commotion outside his window. He walked outside to behold an empty pool surrounded by a small mob of angry trekkers. Brad looked side-to-side, lowered his voice even more, and then said: “Everyone’s upset—trekkers, locals, everyone. It seems that sometime during the night, someone, some fucking moron idiot, has pulled the plug out of the bottom of the pool—the plug that keeps all the water in—and spread the damned thing on a bush, and now all the water’s drained out. Everyone’s looking around, searching everyone else’s faces, wondering who did it.”

The pool was relatively slow to fill with the feeble trickle of thermal waters, so it would take more than a day to reach its level the night before. When Beverly awoke, Brad advised her that it was time to quickly get on with the hike. He hadn’t explained why.

By the time Brad finished the story, he and I were in hysterics. My chest hurt so severely from laughing and coughing out hash-pipe hits that I had to put my face down on the wooden table and cover my mouth. Too bad we were the only two who knew the drained pool’s hilarious truth. But no one else could know. Not harm to me, I thought. I wasn’t going into that murky vat of trekkers’ sweat. I couldn’t help but ponder whether Brad and I might become good friends if we ever saw each other again back home after the trek.

*

The next morning, Marianique and I arose and ate breakfast on the porch in the brisk air. I wore shorts and sandals, expecting to warm in the rising sun and lounge the day away—and because my blue jeans were so filthy, they were no longer blue. Mentally prepared for serious slack time, starting with a bowl of Champa porridge and Tibetan bread, I was chagrined to realize that the Tatopani scene repulsed Marianique. She hadn’t come for the mobs. She glared at them. Granted, we were all jammed in around a small collection of trailside lodges, but it was a wonderful, relaxing place—and almost warm. Notwithstanding, she made known her wishes to walk out early. I obliged her for reasons I didn’t understand, and we soon “saddled up.” We were trudging away before the sun was an hour over the peak tops.

Part of my resistance to heading out was the knowledge that we had a 5000-foot climb back to Gorapani. My mind wasn’t ready for that. Perhaps Marianique knew the fair-weather jig was up and that we needed to keep moving.

*

The afternoon storms kept after us. When the clouds began their towering afternoon swarm above our heads, and downdrafts of cold air changed to rain, we ran for the canopies of trees or bushes. And we hastened our pace. In that way, harried and damp, we arrived back at Sikha, the little village of the two dying men. Then came the lighting, thunder, and hail, shaking the buildings under which we cowered and startling the water buffalo in the nearby paddies. The deluge continued all afternoon, so we sat and ate under a covered teahouse porch, spectating as if in a Las Vegas dinner show.

Sikha wasn’t one of the primary trekking destination villages, so it lacked a high density of lodgers. Besides us, there were only three other trekkers there. Yet, the village had a moderate population and a busy feel. Late that afternoon, after the storms subsided, the woman who ran our cafe approached us. She spoke a little English and we had communicated with her, admiring her little children as we tried to piece simple sentences together. Perhaps enamored with Marianique’s polite disposition, maybe assuming we were a married couple, she took a liking to the both of us. She eventually coaxed us away from the café where the other trekkers were eating with a “You come with me” gesture. She wanted to ask us something.

I was taken off guard and wondered if the previously sick men had died; if my little black pills had been blamed, and if she was inviting us to a Nepalese trial and hanging.

Out of earshot of the other trekkers, in bits of broken English, she told us there would be a wedding ceremony later that evening. Most of the village would attend. It would be a bit of a walk, out on the hillside at sunset. She wanted us to attend as her guests. Marianique and I looked at each other with wide eyes. We didn’t require the typical couples’ discussion about whether it would fit our busy married schedule – we just motioned our acceptance. “Fuck Yes!” I politely nodded.

Marianique and I tore into our backpacks to find anything presentable for a wedding. Sadly, we had nothing but smelly, crumpled clothes. We cleaned up, donned the best outfits we could muster, and soon followed the woman down a narrow path through the weeds and under the trees. We walked for fifteen or twenty minutes until the trail popped out of the forest into a small mountainside village of thatched and tin roofs. I wondered how many hidden settlements like this dotted the Himalayas.

The wedding convened on a hillside earthen platform, presumably dug by pick and shovel since no earth-moving equipment could have gotten there. There was an unobstructed view northward to the frozen faces of Dhaulagiri, southward to terraced fields dropping away for thousands of feet, and to pink swatches of Rhododendron forests on the surrounding ridges. As if part of the extended family, water buffalo grazed docilely nearby. The sky above was adorned with the broken remnants of the afternoon thunderstorms, catching the golden afternoon rays of the sun.

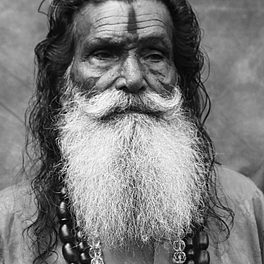

Attending villagers wore wildly colored clothes that matched the vivid sky and Rhododendron flowers. Long Tibetan horns blared while drums beat and attendant monks chanted. Tipsy men consumed ceremonial Chhaang. Eventually, two young people were united amid teary faces, exuberant families, and a crowd of friends. The celebrants took absolutely no notice of Marianique and me. We stood like flies on the wall, soaking it in, awed by the surrounding mountain scenery, and thankful for the serendipity that drew us there.

*

Steeled quads brought us back up to the mountain village of Gorapani by mid-afternoon the next day. Standing in its center, we witnessed a community that seethed with the daily chaos of children yelling and playing, women cooking and washing, men carrying and constructing, and birds screeching down at everything and everyone. From the tree in the center of the village hung the torn prayer flags that still flapped in the breezes as they had some twelve days before. We took it all in and then ducked into the Mountain View Lodge, where we dropped our packs.

It was time for tea and food; and a visit to the open-air shower corral to wash with a plastic bucket of hot water.

Soon, the afternoon grew dark, signaling that the daily dose of storming had arrived. There was distant thunder and some light rain. Then, small hail began falling from the sky–nothing abnormal. No one even looked up. But then the hail inflated to the size of Ping-Pong balls. It raged down and pelted everything, muting all other noises. But the sky was just getting started. When it finally let loose, you could barely see from building to building. We were in a blizzard of ice balls. Leaves fell to the earth, stripped from the trees. Branches fell, too. Village children covered their ears. People ran for cover.

The Mountain View Lodge’s tin roof promptly began leaking under the barrage. Trekkers scampered about moving belongings away from wet spots. Everyone inside stood gazing upward, wondering where a new roof leak might emerge. As the storm intensified, hailstones began to penetrate the smoke ports—they bounced around on the wood floor. Through the din, the fire pit in the lodge’s center wafted smoke upward to burn our eyes, soot up our clothes, and ooze out through the ceiling. When water and ice balls found their way into the flames, they sizzled away in puffs of steam.

If anyone tried to ignore the spectacle of the hail, incoming bolts of lightning and crackling thunderous retorts shook them into startled awareness. The lightning was so close that no gaps existed between the sound and the light. We could smell the ozone. It was as if the village was in a war–and Mother Nature owned the artillery.

But, in less than an hour, the barrage suddenly stopped. The ground was left a few inches deep in white icy balls interlaced with green leaves and rosy blooms stripped from the surrounding Rhododendron trees.

Walking outside our pummeled lodge, awed by the spectacle and its aftermath, I took in the sudden change to the village. All routines had been disrupted. Now, the villagers were picking up broken branches, downed laundry, and sweeping hail from their lodgings. Even the birds had been silenced.

I looked up at the hillside above the village and saw a white trail winding upward into the trees. It was the way up to Poon Hill. I imagined the mountainous panorama from the top, a fresh white carpet of hail, and the receding lightning in the distance. Usually a dirty rutted trail, it was now a glistening hailstone path, leading Oz-like up through the forest.

The trail beckoned to me. I ran. It was like running up an ice-covered slide.

Halfway to the top and wheezing in the thin air, I suddenly realized that Brad and Beverly were back in my same lodge, just sitting inside, ogling outward at the storm’s aftermath. I wasn’t sure about Bev, but I knew Brad would want to be with me, spectating at the clearing skies and the surrounding peaks from a bed of hail. After all, Brad was an Afghan wanderer and drainer of fetid swimming pools. He had to come. So, I stopped, turned around, and sprinted back. It was a Slip-N-Slide stumble all the way back, and I slid off the trail several times. Back at the lodge, everyone was still skulking under rooftops.

My impulse was dead on. No sooner had I found them and shared my vision of the hail-covered Poon Hill panorama than they both threw on their shoes and jumped up to follow. Together, we bolted back up the icy path.

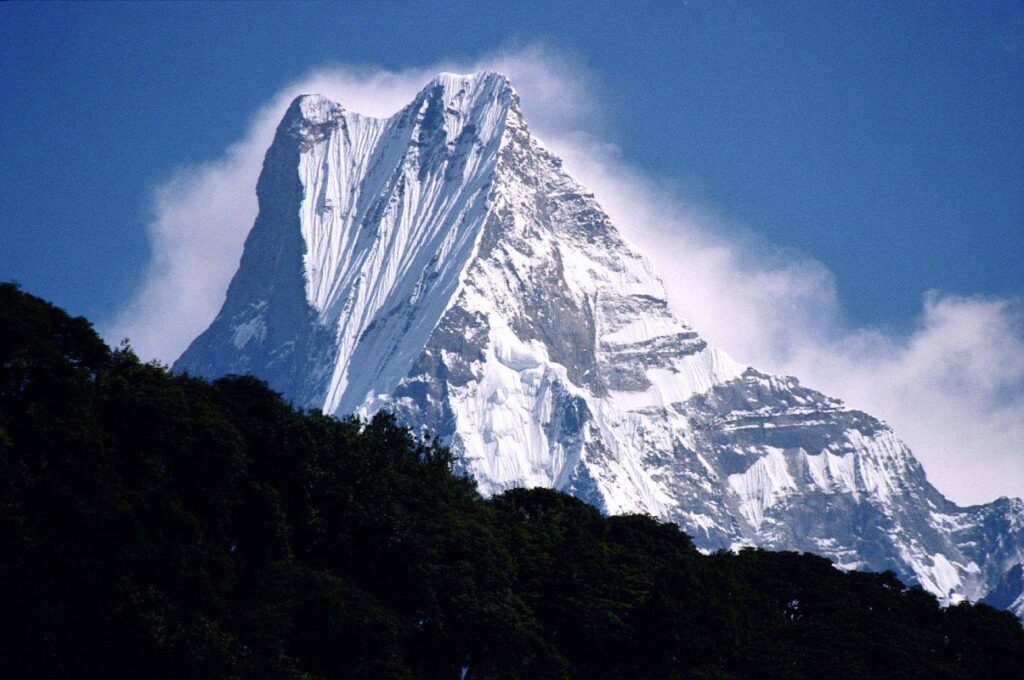

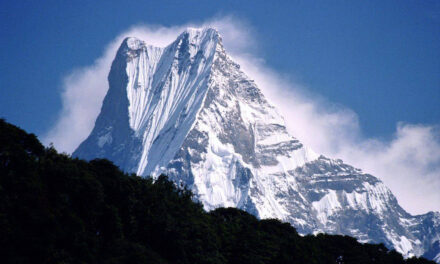

Some ten or fifteen minutes later, I emerged from the dripping forest onto the hilltop. Sweating and panting, I beheld what looked like some pop artist’s rendition of the opening scene from Sound of Music. The grassy hilltop was buried in inches of hail. The afternoon sun poked through holes in the clouds in long beams, accentuating parallel rows of mountain ridges stretching west as far as I could see. Northward, Dhaulagiri wrestled with a massive cloud that fought to obscure its ice-clad face. Northeastward, the Annapurnas and Machapuchare took turns shattering wind-blown thunderheads that tried to obscure their lofty faces.

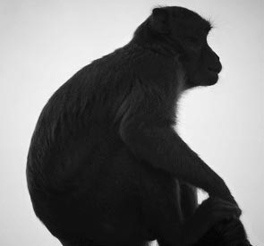

Clouds to the south then stole the show, presenting a foreground of white cotton balls against a backdrop of radiant apricot skies. The surrounding pines added a dose of green reality to the overbearing pink and red Rhododendron trees looming over the white carpet. The birds and monkeys soon came to life from among the trees and commenced yammering down at us.

All I could think was, “This is nuts!”

As I stood there, more people appeared from the trail. We were silent, awed. You could hear feet crunching on the hail—like pins hitting the floor in a quiet sanctuary. There was reverence—the same reverence I experienced in the York Cathedral, in Saint Peters, at the Taj Mahal. More, maybe. The storm, just a routine monsoonal deluge, was so much more. It was a call to us. We all knew it.

My mind stretched like the mouth of a snake painfully deforming to accept prey too large. What surrounded us was impossible—beyond any camera’s capability. A camera would have been a distraction. This gift–that’s what it was, really–was so exquisite, so grand, that even the exchange of words would have defiled it.

Still, there were words to be heard up there: Wow! and “Oh my god!” and Holy shit!” and such. I might have even heard Brad mutter something, but my head was elsewhere—I was lost in the surreal.

Whatever bestowed this spectacle had rattled the skies to prod us. It got our attention righteously. We’d been jarred up from our cleaning, naps, and dinners, and then, enraptured by the call, some of us had clamored up the slippery slope. And there we witnessed the sublime—all on a fresh white stage in a Himalayan sanctuary.

Standing on that hilltop, it struck me that all the shit in the world–whether failing airliners, near-death experiences, even childhood traumas–didn’t really matter. They were chaff. What mattered were these transcending glimpses of the mighty universe that we were a part of: these moments.

I imagined some omnipresent force booming down to us from beyond the clouds, expressing divinely but without words, “Behold THIS, you earthly cretins!” and then throwing down a lightning bolt for extra emphasis.

A million thoughts went through my mind.

Was this beautiful spectacle as enlightening to the monkeys in the trees as to the humans below them? I had seen monkeys watching sunsets.

How far back did our ancestors stop their hunting and gathering to watch a sunset or “Whoop!” at a clap of thunder?

Were we naturally selected to appreciate these earthly moments? After all, the most fearful hominids might have huddled away from lightning and tigers in damp caves, eventually starving and dying off. They got depressed. Perhaps we survivors were the ones inspired—eager to be outside and active, whatever the cost, just to witness another day.

How ironic that the most significant “Ah Ha” moment on the trek was revealed amid our retreat from where I thought I’d find it. You just never knew.

“Too Much!” I thought. No words.

Inwardly, I mused at everything I could NEVER grasp in the cosmic scheme of things: those unexplainable moments, the indescribable events, and the constant serendipity. It was all those things that made—in the words of a young Brit passing me a joint on a Cairo rooftop three months before— “this crazy old world.” We were nothing. We understood nothing. And if our eyes were closed, we missed that.

***

NOTE: Brad Newsham’s descriptions of the Tatopani pool event were from his written (and somewhat contemporaneous) account, which he shared with me during the final editing of this chapter. During the many years following our Jomsom trek, Brad published several books on varying topics, all related to the enlightening process of wandering the world.

Ah, what fun Steve! Forty-one years ago… You’ve brought that Poon Hill moment back to me on a level that I, honestly, haven’t experienced in all this time — quite the unbelievable stupendous moment — the sort of thing we travel in hopes of, and when it happens it leaves us stupefied, not knowing what to do with it… Thank you for keeping it alive for me… And I think I’ve forgiven myself for my Ugly American-ness there at the hot springs…. No excuses… I was thirty years old. Now I’m 71… I’ve made much bigger mistakes since then… Loved the story…