The morning after the Valley Girl lost her composure, Marianique and I packed up our backpacks, dined on the Red House gruel, climbed back through the gauntlet of ladders and horse pens to frigid daylight, and then began the slog upward toward Jharkot, a village halfway to Muktinath. Somewhat off the main route, according to our map, Jharkot seemed an interesting midway point for an overnight stop. We saw no trace of the Californian. Happily, my trekking partner seemed to have put that dark incident (and the mysterious Doug) behind her.

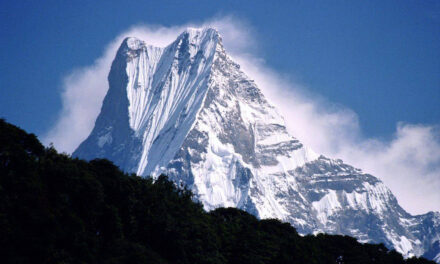

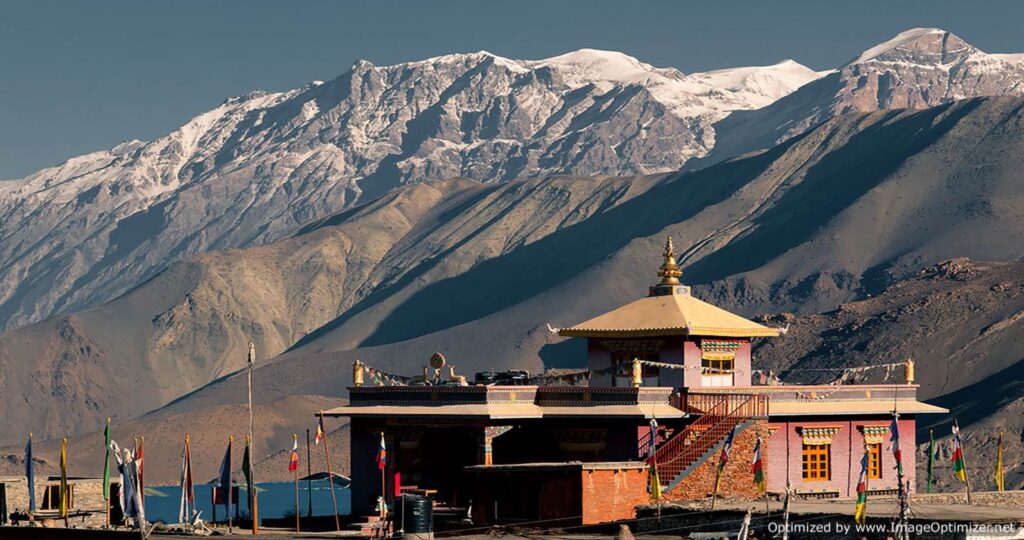

Jharkot was a larger settlement than Kogbeni, situated upon an 11,000-foot protruding blade of rocky earth in the middle of an ascending valley. The place was windswept, like a forgotten mining work in the scrub of northern Nevada. But there was no mining there—just meager living. Below Jharkot’s rocky perch were green terraces that looked to grow much of what the inhabitants ate. Yaks grazed the low grasses on the hillsides. At an elevation higher than almost every peak surrounding the Lake Tahoe basin, the city sat more than 15,000 feet below many nearby peaks.

White and orange-painted buildings rising from Jharkot’s center appeared like square ornaments on a dead Christmas tree. Mountains on both sides, trimmed with dustings of snow, rose to great heights, pushing to the clouds. It was a bone-dry place, cold like the peaks that blew down icy gusts. Eagles silently circled above on updrafts. Everywhere, dogs with nervous wagging tails barked viciously. Happily, they were tethered. As the day waned into a pink sunset, the surrounding peaks lit up and shone like fluorescent beacons.

*

We dined that night at the frigid Jharkot Lodge, where there was little light and no fire–just coldness and too few blankets. Cabbage soup, Tibetan bread, and vegetable Momo were followed with hot chai. After eating our gruel with shivering hands, we sat back on the rocky floor of our mud-walled building. The wind whistled above us through the drafty tin roof. We fidgeted and couldn’t sit still. It was simply too cold and uncomfortable. But it was much too early for sleeping bags.

I motioned to Marianique, my incommunicado companion, with walking finders on the palm of my opposite hand and pointed to the door. She nodded. Then we rose from the floor, put on all our clothes against the outside night elements, and walked out into the night air.

There was a full moon that night. As we strode away from the village, stumbling over shadowy bushes and rocks, dogs barked at us from the village. We circumnavigated Jharkot on a freeze-dried landscape illuminated in dull lunar light and a skyful of stars. An arctic wind blew down from the snowy ridges and penetrated through our multiple layers of inadequate clothing, chilling us to the core. In all its beauty, this was a severe and ruthless place. Our walk didn’t last long.

Back at the lodge, we gathered all the available blankets, and then each rushed to the warmth of our sleeping bags. Still, the cold crept in, chilling my knees and numbing my toes for the entire night. There was no warmth there.

*

Jharkot’s resources were meager. The apparent minimum of food and possessions was a cultural norm I couldn’t fathom. Yet, despite that environment, these people lived cheerfully in these remote and beautiful mountains more than sixty miles from the nearest road, with no medicine, sanitation, or other Western “necessities.” One would think their lives would be as bleak and miserable as their threadbare existence, yet they jovially carried on as if they didn’t know what they were missing.

I felt spiritually inept. These people—Nepalese, but really Tibetans—had so much life and vigor with so little stuff. They were beacons of strength, vitality, and good cheer, unfazed by their material deficiencies. Back home, there seemed only a mild appreciation for all we had at our disposal. We have so much—we have it all. As some go into the Peace Corps, and as Israelis go into the military, I couldn’t help but think that every American should have the experience of spending a cold night dining on cabbage soup and sleeping under the drafty roofs of a village in the Himalayas.

*

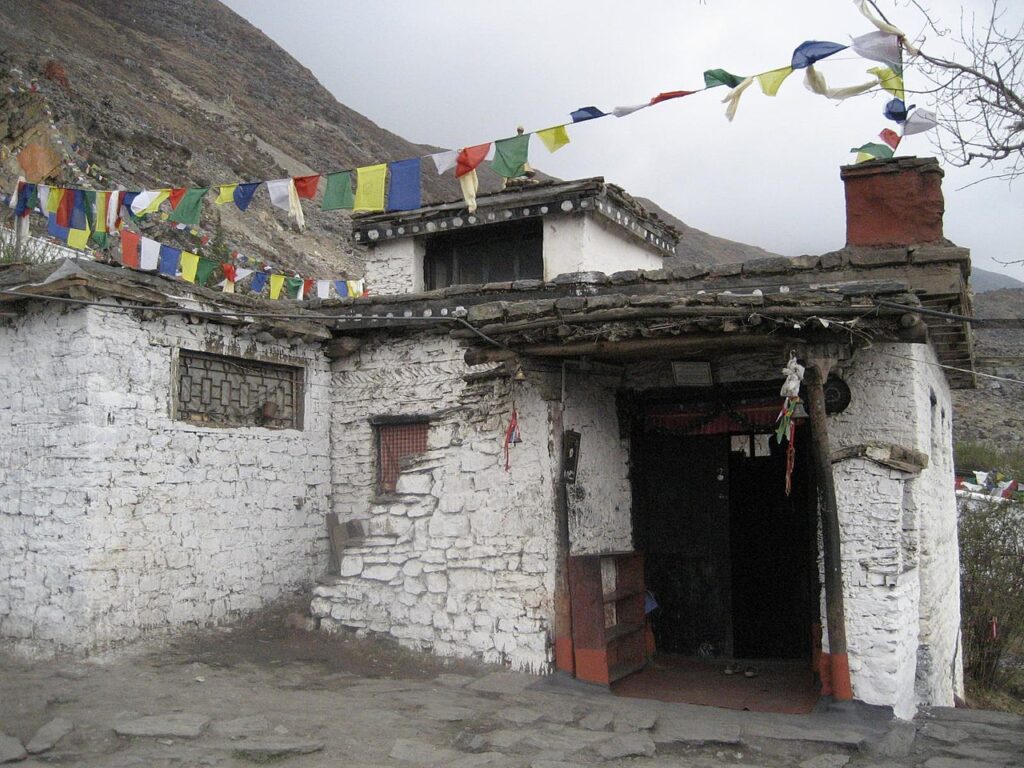

Muktinath was not really a village, but a scenic 12,500-foot stopover consisting of a few rock-and-mortar buildings, some trekking lodges, and a holy Hindu shrine—the Jwala Mai Temple. As far as trekkers are concerned, it’s the last stop before Thorong La Pass, a 17,700-foot low spot on the north side of the Annapurna Himal. For pilgrims, however, it’s the ultimate destination.

At the Temple, legend has it that all the earthly elements spring forth miraculously from a holy flame in the mountain rocks. Those who see it are purportedly transformed and reconfirmed in their Buddhist or Hindu faiths. That’s what they say. Most of the trekkers were too cynical to pay even the nominal fee to check out the miracle. But I had to make my inspection. So I paid a rupee, removed my shoes, and entered the shrine under the watchful gaze of an old caretaker. She eyed me as skeptically as I entered. I eyed her back in the same manner.

The shrine was so cold and dark, I had to brace myself as if entering a meat locker and then let my eyes adjust to navigate over to the divine phenomenon. I was naturally curious about the fire, but a rope kept me at a respectful distance from the spectacle. There I observed what appeared to be something like one of those 1960s rotating, simulated fire logs with colored aluminum foil and orange lights. The glow was mysterious since there was no electric power in Muktinath. I assumed the “flame” was sunlight reflected off mirrors since the temple closed uptight at night.

In any case, the caretaker promptly hustled me out when I tried to approach the flame with what must have been an analytical look in my eyes. Pilgrims came many miles to see the elemental fire, often dying on the way—as did the reposed Sadhu along the trailside. No Westerner was going to spoil that. “Sorry!” and “Namaste,” I said as I left.

*

On the second day at Muktinath, Marianique and I packed up some food and water and headed up a trail making its way away from the Annapurna Circuit course and toward the north rim of the valley. It was not on the map but it looked like it was traveled. We’d first tried heading up the Thorong La Pass trail, but wind and snow had pummeled us, and we quickly became out-of-breath, shivering zombies, so we had turned around. We had been barred at gunpoint two days before from heading along the river trail toward the forbidden Mustang, so we now felt more compelled and less tolerant of obstructions. No more obstructions. Plus, we both wanted a glimpse into Tibet.

Our trail was unmonitored by any authorities. It cut across the valley and then switched back and forth, ascending toward a notch in the high ridge. There were exposed fossil shells in the trail cuts that might have stopped me in my tracks under normal conditions, but I ignored them and kept pushing ahead. This was a mission. The path was a lonely one, and we saw no one else. As we pushed upward, clouds swept in, and it snowed intermittently. Ignoring the elements in our insubstantial gear, we picked up the pace. In my mind, I decided that we needn’t turn back as long as the snow wasn’t falling enough to obscure the route back. Periodically I turned around to check on that.

We reached the trail’s summit in the afternoon, standing upon a high cleft in a snow-dusted ridge. The notch provided sweeping views of the northern horizon between the clouds. I imagined I saw Tibet in the distance. I knew the border wasn’t far from the ridge, and we could periodically see for fifty miles or more. The barren landscape stretched out and away from us, a brown and ridged moonscape forever. The flat, arid terrain was dotted with the shadows of moving clouds like an American high-desert winter scape.

Marianique and I stood on the pass, shivering, for what seemed to be the better part of an hour. We might have been at a 15,000-foot elevation as Muktinath was far below us to the south. Did our little trail continue out into the canyonlands beyond? Were there more villages where we might stay? Would villagers off the main trekking routes have food for trekkers? I didn’t know the answers to those questions, and my map didn’t tell me. Yet the trail appeared to be used, as there were occasional prints of boots and hoofs.

We were at the boundary of our mental willingness to proceed further, a line beyond which we could go—but all bets would then be off. It was a line. With my boot, I scuffed a shallow ditch across the snowy trail and then watched as the wind gusts blew the snow right back.

I was torn. Part of me wanted to keep heading north to see what was out there.

Split, my curiosity begged to continue while my body urged a return to warmth and food. Eventually, the cold became real, even after we’d donned all the remaining clothing we’d packed for the day. We needed to keep moving—whatever our choice of direction—to stay warm. When it began to snow in greater earnest, Marianique and I didn’t even need to communicate. We finished the last food, turned, and retreated to Muktinath.

Mindful that we’d made a responsible choice–albeit not the most exciting one—I felt a great loss. This was undoubtedly our ultimate turn-around point, and I didn’t like that idea. Not one bit. As we trudged back, I felt part of me was still up there on the windy ridge staring northward. Maybe a small part of me would stay up there forever.