The old Egypt Air 737 slowly rose from the bumpy runway and soared upward into a bright clear sky. It ascended over the Nile, curved over Giza, crossed the outer edge of the vast dusty metropolis, then, completing a long arc, headed south.

I was glad to be leaving Cairo. The city was a cesspool. There were too many people and the streets smelled like sewage. Young Egyptians followed me incessantly, especially the children, wanting to “practice English,” or show me Cairo, or “be my friend.” I was tired of the western females coming to me for protection, for my escort, because they had been harassed, groped, and propositioned by the local men

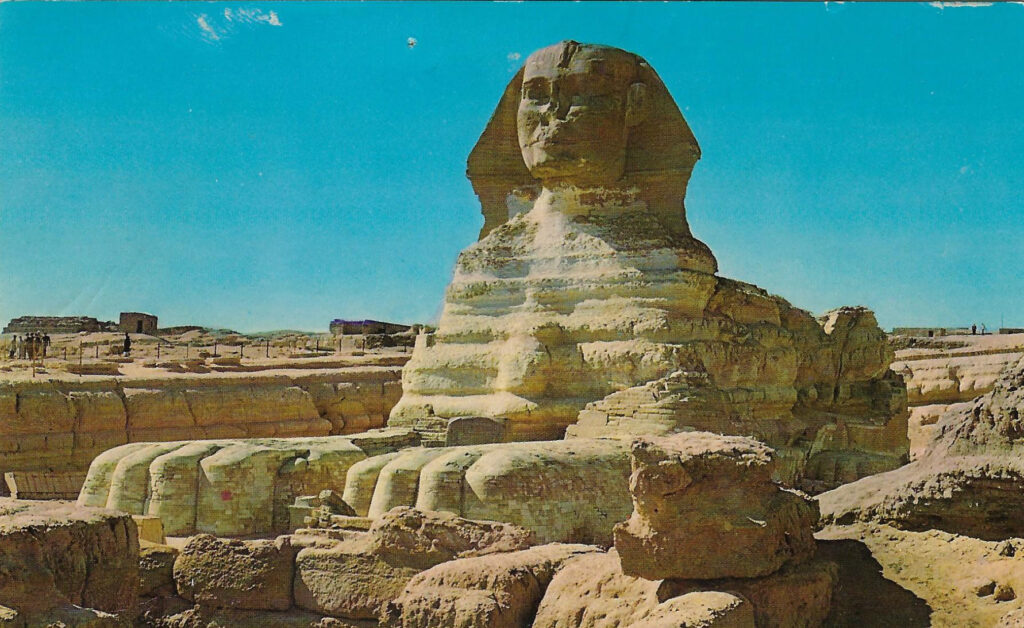

Still, Egypt had been fascinating. Giza was eerily aesthetic for such a trampled ruin. The Tutankhamun exhibit was staggering, both in its size and its apparent metallic value. Several crimson sunsets on the Nile were entirely surreal. And I had befriended several intrepid travelers coming back out of central Africa.

As the jet ascended southward on its eastward course, the Nile valley dropped away below us. Then the utter starkness of this part of the world became apparent. The desert extended in every direction. There was nothing green on the horizon—nothing; just dunes, rocky plains, and desolate peaks.

Yet, within the Nile floodplain everything was green. There were irrigated farms, orchards of palms, canals, and boats of all kinds on the river itself, including those with the primitive sails depicted in school textbooks.

Pyramids were everywhere, on both sides of the river, mostly at the edge of the Nile valley escarpment. I had no idea there were so many. Their shapes varied dramatically from the broad Giza style, to those that were steep and pointed. Many stood in groups of threes and fours. There were also curious mounds and other apparent man-made structures. It looked like some giant child’s handiwork at the beach.

I moved about the partially-filled jet, seeking windows on the right and left sides, taking it in. My aerial reconnaissance of Egyptian geography continued for about forty minutes, at which time the jet started emitting a strange grinding noise from somewhere in its underbelly.

*

I suppose I took my chances on big jet planes during my travels. American-made 737s were still the safest in my book. They were the working dogs of the passenger routes, with well-secured, amply-powered, and reliable engines, not the flimsy Tri-Star designs that had issues in the 1970s. 737s were stout. It was rare to hear of one crashing.

Most of the 737s I encountered on my wanderings were piloted by captains with British or American accents. You’d hear it on the intercom before the jet even left the tarmac. That implied far more than a place of origin. It evidenced where the flight training and technology hailed. It gave me confidence—but you never really knew. My hard and fast rule was never to place a foot aboard Aeroflot. Those went down. And this airline?

The US airlines industry put out a statistic that people were far safer flying in commercial aircraft than moving about in automobiles. Catchy data point. Yet car crash statistics included every oblivious drunk who ran into a pole and snuffed out the lives of himself and his passengers. They included the idiot reaching for the gum on the floor, or simply falling asleep. They included inherently bad drivers. Diligently defensive drivers were far fewer among the auto mortality statistics, in my mind, since they paid stricter attention, swerved from oncoming trouble, and never let a drunk take the wheel. They lived. Thus the defensive crowd had a lower kill rate than the automobile crowd at large.

On the other hand, those in the imprisoning passenger compartment of any crashing commercial aircraft most assuredly all died. “Responsible” or not, if your time came on a jet, there wasn’t much you could do.

*

The sound beneath the jet was like the grinding of failing gears, and it was loud. Each noise lasted perhaps five seconds and then stopped. That went on for ten minutes or more. After the seventh or eighth round, the jet dipped into a lazy U-turn that brought us back around, facing northward toward Cairo. The noises continued intermittently. It seemed like someone onboard was trying to make a reluctant mechanical system perform.

Finally, the pilot came onto the audio system and, after tapping the microphone to gain everyone’s attention, said the following:

“Ladies and gentlemen, this is the captain speaking.”

Everyone perked up and listened.

“Unfortunately, we have encountered a slight technical snag with the aircraft. We have changed course and will be heading back to Cairo. Sorry for the inconvenience.”

He gave no further explanation. My only relief was his American accent—and my knowledge of the extensive flying experience of American military pilots, his probable background. Following the notification, there was a murmur of frustration among the passengers.

As we headed back on our new trajectory, the jet descended and our ears popped. We went down and down so far that I thought we might be heading for a hidden landing strip. Eventually, we were right over the desert floor, several hundred feet above the dunes. I could see footprints in the sand. By then, the grinding noises had subsided. Maybe the problem had been resolved.

From the grinding-like sounds, and their durations and apparent source beneath the aircraft, I deduced that there might be a problem with the landing gear. Of course, there was no way to see if the landing gear was being extended or retracted because I was on board and the landing mechanisms were beneath the jet and out of sight. There was no way to know much of anything.

I kept looking out the window for answers. Then I noticed a great shadow coming off the eastward wing in the afternoon light. Looking more closely, I saw liquid pouring from and glistening on the back part of the wing. Shit! The jet was dumping its fuel. That created the shadow below us. This continued for several minutes, then stopped. We then gained back some of the lost altitude. I’d heard of that protocol. The hair stood up on the back of my neck.

Soon after, the captain came on the sound system again and asked for one of the flight attendants to come forward. I watched one of them walk down the aisle and disappear through the cockpit door.

*

The selected flight attendant eventually exited the cockpit and then called the rest of the all-female crew of attendants forward on the intercom. She looked stern. As the others came forward from various sections of the cabin, one pulled a curtain across their space to shield them from view of the passengers.

Five minutes later, the attendants pulled back the curtain and advanced down the aisle. Now they all looked stern. They directed passengers to stow purses, carry-on luggage, and other loose items–stowing everything. The attendants conducted themselves with a distressing sense of thoroughness. The head attendant then got on the intercom and announced that they were just going through “normal protocol” for the landing back in Cairo.

Once back up to a reasonable altitude, the grinding noise re-commenced and repeated, over and over, like something still wasn’t working but was trying to. My hands began to sweat. My eyes searched for any clue as to what was going on.

Two attendants ducked back into the cockpit. They emerged a few minutes later and conducted a re-briefing among the others, then came back down the aisle again. All but one, however: she sat down in the reverse-facing crew seat a few aisles in front of me, faced out the window, and began to sob. She covered her face and her body shook.

*

I wondered to what degree a risk-fraught life could change the odds of one’s survival. The more risks, the worse the odds. Was that the way things were going? Still, as we learned in mathematics, odds were odds—they didn’t increase with repetition. And calculated odds? Those were always better.

The visitation with Abdul in Morocco should have given me more circumspection about risk—especially abroad. It had. Yet my friends and I had subsequently proceeded to play high stakes poker with the Moroccans for the better part of a month, exploring all the medinas at night, traveling by dilapidated public transport, eating the local cuisine, trusting the untrustworthy to show us around, even purchasing a Riff pollen ball from a dealer who predictably called the authorities. But we discussed our risks, calculated the odds, and always evaded trouble.

My travels were turning into an ongoing game of escaping.

I’d escaped from a barroom knife fight in Austria as I had a melee in Hawaii years before. I’d escaped numerous near car crashes by flashes of insight and quick evasions. I’d been present at a few “busted” parties in high school, but always sensed the approaching authorities and disappeared at the right moment. Even a few mountain predicaments were avoided by my odd sense of foreboding. Had I been lucky or just aware? Maybe it was a bit of both.

In any case, whether it was good luck running out, or bad odds creeping in, there was no escaping what seemed to be going down on this flight: everyone. I wanted out, but I was stuck. I would have switched my seat in a second for the panicky discomfort of my old Godzilla nightmares.

A bead of sweat rolled down my cheek and I wiped it away.

*

During the second sweep of the cabin, one of the flight crew got on the intercom and directed that “absolutely everything” be placed under the seats or in the overhead bins. The attendants double-checked that latches were closed and secure. They searched for, found, and stowed the pillows and blankets.

By then, the passengers were becoming nervous. Many were asking questions in a variety of languages. But none were given definitive answers. The same question was on everybody’s mind: were we going to crash? The attendants responded to questions with stiff-looking smiles.

The aircraft lumbered back over Cairo where I could see the airport in the far distance. The grinding sounds emanated throughout the aircraft again, no different than before—still a terribly dysfunctional sound. As we descended toward Cairo International, the attendants came around a third time. This time it was to show all the passengers how you put their heads down between their knees for the upcoming landing. The crash position. We were told to assume that position for the final approach.

This elicited distressful moans from many of the passengers. Others began to cry. Sobbing adults comforted distressed-looking children, who didn’t understand what was happening but were freaked out by the way the adults were behaving.

I heard prayers in several different languages. Religious beads clicked in the nervous hands of a woman sitting across from me—her lips moved in silent prayer, eyes closed. Someone began wailing audibly from behind me. A woman who held a small child close to her chest glanced back at me briefly, as if to see my expression. She had a look I‘d seen on a dog’s face once—just before I hit it with the car. Most of the passengers just silently sat looking nervous and morose. We were trapped and there were no evasive actions to be taken.

*

The jet made a low, slow pass over the airport. The grinding noises continued intermittently from somewhere under its belly. I moved up to a viewier window and looked down. The runway was lined on both sides with the flashing lights of emergency vehicles, a red and white parade waiting for the arrival of some mutilated dignity. I blinked at the scene in disbelief, hoping it would just go away. Adrenaline rushed through me and I felt the need to flee. But there was nowhere to go.

It occurred to me that our fly-over might be to enable experts on the ground to visually confirm whether landing gear was properly deploying. The grinding noise might well be the gears in the wheel mechanism. Perhaps a belly landing was a likely scenario. Maybe we’d skid in on the sand. There could be worse scenarios. With no fuel, and assuming sand wouldn’t generate sparks, there might not be a fireball. We might live.

My brain raced, my heart pounded, and my pant legs grew damp from my sweaty hands. I‘d flown in troublesome weather before, but never encountered the real possibility of a crash. My good friend, Scott Whitney, had seen a crash of a small plane in El Dorado County. He had raced to the crash site, first there, but was unable to extricate the passengers and then watched as they perished in flames. Shit!

As I sat, confined to my seat, I thought about god, and destiny, and statistics. I hoped that death, if that were coming, would be quick. No reason to die slowly in the flaming wreckage of a jet.

*

There was a marked increase in the moaning and sobbing within the cabin. Like me, other passengers had looked down at the spectacle on the tarmac. We made a second final high pass over the airport and then began to drop down in a wide circle. Every bump and jiggle startled the passengers. Maybe we’d stall out and fall from the sky like a rock.

I listened for any noise that might provide a clue—or a hope. The flight attendants were strapped tightly into their seats in five-point harnesses with their eyes closed. One had tears rolling down her cheeks. Another made the sign of the cross on her chest. I took it in and looked away from them. I’d fight my own battle with fear. Anyway, it must be landing gear. Why else would we have passed directly over the airport if not for someone to look up and scope it out from the ground?

The aircraft banked sharply, dropped more, straightened out, and then aimed toward the black strip with the flashing multi-colored lights. Now it was just a matter of waiting a few more moments for the crash: the wrenching and the tearing of metal and flesh as the craft tore itself apart on the landing strip. Had we spilled enough fuel? Did we now have enough? Life was wholly out of my control.

I could have prayed. I even prepared myself for that mental state as I had so many times before in my younger “church” days. But I stopped. I was not a believer in an intermeddling god of micromanagement; of “Help me!” prayers here or “Save me!” prayers there. Nor would I be lured to a foxhole conversion out of this panic. I’d be faithful to the laws of physics and to the certainty that humans knew little else about much of anything. This aeronautical issue was neither karmic nor heaven-sent. It was, as the captain initially announced, a “technical snag” with the aircraft, whatever that meant. This was random.

I remembered when I nearly drowned at Newport Beach while trying to hang with my surfing cousins in some big Pacific surf. A twelve-foot wave had stripped me of my board, slammed me down, and pushed me deep underwater. I was a good swimmer, an ex-Dry Diggins Dolphin, and had grabbed a breath of air as I went down, confident I would find the bottom and push off back to the surface. But the churning was so severe, up-down-and-sideways, that I couldn’t find the bottom. I didn’t know up from down as one wave came quickly after the other. Several of my attempts to reach the surface failed. Then my desperate struggle succumbed to lightheadedness, to transition, and then to bliss. I came back to consciousness when a woman on the beach, who had seen me lying face down in a foot of water, had run down to save me. She lifted me up and I sputtered back to life.

That near-death experience wasn’t painful. There had been fear and I had put up a fight, but in the end, a dreamy submission had taken hold. It was not unpleasant. I supposed the impending crash would be the same. Fear, then dreams. Still, I was profusely sweating.

*

What does one do in the face of their impending demise? At the very least one does something, defensive or evasive. But there is nothing much to do on an airliner unless you’re a pilot. I could only sit buckled into my seat.

Wholesale wailing now permeated the cabin. I looked up from my forward-bent crash position and sensed terrified souls. The passengers were all preparing to die. They were in each other’s arms, eyes clenched closed, stroking the heads of crying children, blubbering, and praying to Christian, Islamic, and Hindu gods. I felt the weight of a great collective sorrow. The moroseness of the passing moments made me think of all sorts of things.

There were things I had read concerning predestination, karma, and divine miracles. Yet I had no idea if any such things were real. Moreover, there were many forces and events that humans didn’t understand. Humans interpreted such things in the manner that the three blind men had interpreted an elephant by touch: way off-base but maybe onto something. I’d had a few odd experiences of my own: dreams where I’d talked to the deceased; premonitions of events that had later happened; witness to auras surrounding animals while doing a peyote walk out in the Mojave. More than once I’d seemingly made people turn around by staring into them. My religious friends found a myriad of things possible through faith; albeit that was their hope and expectation. So what was, or wasn’t, possible? I had no idea.

Was I ready to die? No. I had most of my life to yet live. And if I were to die, my family wouldn’t be the wiser for days, maybe weeks. That would suck. They didn’t deserve that.

And what about all the other older passengers? Many were parents, some with their kids in the next seat. Most probably had children waiting for their return from wherever they were traveling. They all had people who depended on them. Their extinction would be crushing. Most crushing was that they all realized that as our aircraft descended.

I closed my eyes and opened my mind’s doors, listening to all the terrified, sobbing people seated in the cabin. As if in a deprivation chamber, I pushed out my presence. I imagined all the sweaty nervous hands fidgeting on laps in the cabin. Could I mentally grasp them and hold them tight? Could I exude reassurance even if I didn’t feel reassured myself? Maybe I could distract a fearful soul or two as our speeding mass of flesh and metal slammed into the earth. Was that madness? Was this prayer?

Part of me realized that it was ridiculous and vain to think that I could perpetuate anything but my warped delusions upon myself as we intersected the earth. But who knew? There were forces out there about which we humans were clueless. In that warped mindset, I descended with the rest of the helpless passengers.

*

Suddenly, I could sense the flaps extend. There were more grinding noises. The jet lurched. I dared not glance out the window. We were dropping down, down, down from our low cruising altitude–a thousand feet, a hundred feet, thirty feet in a decelerating manner. I sensed the flare out, then a momentary floating, as if hovering just above the blackness of fate. Then, still roaring in at break-neck speed, the hovering stopped and we alighted.

The jet bounced on the tarmac with the squeal of rubber. I breathed out, knowing we had landing gear—or maybe partial landing gear. We bounced again, settled onto the runway, stayed level, and then braked. Now we were really down. Above the roar of the reverse thrusters, I could hear the passengers cheering. I looked around warily.

We sailed past flashing emergency vehicles on both sides of the runway. The jet’s brakes strained and its shuddering speed eventually dropped to that of a fast-moving car on the freeway. The jet braked more, and harder, and when our speed was still thirty or forty miles per hour, everything abruptly went silent. All the aircraft’s noises—the turbines, brakes, ventilation fans, buzzing of electrical things, everything—just ceased.

Notwithstanding the shutdown of systems, the jet continued to move. It rolled silently down the runway creaking and bouncing. No longer was there the decelerating drag of the hydraulic brakes or the reverse thrust. The overhead lights and air were off. The dominant noises were the sounds of rattling overhead bins and people talking. The cabin was dark.

It wasn’t over.

The jet just continued silently down the runway. We rolled and rolled with hardly the hint of deceleration. Our path, initially straight, gradually veered left toward the edge of the paved strip. Apparently the steering was out with the other systems. Finally the aircraft left the asphalt and somehow, before the relative flatness of the runway apron dropped away, bumpily slowed until we came to a complete stop in the sandy soil.

Everyone on board let out a collective sigh and looked up at one another. There were smiles on wet faces and several cheers. The 737 sat silently and helplessly, angled off the runway as if some lousy driver had run it into the ditch.

Emergency vehicles pulled up alongside with pulsing lights. I asked two flight attendants what happened, but they didn’t know; or wouldn’t tell. We waited some time before a staircase truck rolled up and placed its automatic ladder to the forward door. When the door was unlatched, we poured out.

*

All the passengers were bussed back to the terminal where they were directed to wait for the next departing Egypt Air flight to Karachi. That meant several hours of sitting. Many just disappeared from the airport, likely going back to Cairo, or home, to avoid another encounter with Egypt Air.

I walked a random and oblivious path through the airport pondering all those same things I’d considered on the aircraft—especially luck. Was this luck? I don’t know how much time passed, but the chatter of other people and the dusty air of Cairo International seemed wonderful. I tried to re-engage the heavier thoughts I’d just experienced, but my brain resisted.

During my meanderings, I spotted one of our flight crew, approached him, and asked him what occurred. What he explained gave me a chill.

Apparently, the jet lost a redundant power system mid-flight. That system was for the operation of all the aircraft’s mechanical and electrical systems. Its absence left the aircraft with only one remaining system; one which, according to the gauges, was also failing. The flight crew knew they had to get down before the only operational failsafe died altogether. They knew it would fail, they just didn’t know when. If that failure were to occur above the ground, we would crash.

That failure did occur, but only after the jet was mere seconds on the ground and slowing toward its taxi speed. Once that system died, the aircraft died—it couldn’t be braked, steered, air-conditioned, lighted, or flown. All wing controls were gone. The ponderous giant literally rolled to its angled stop all by itself.

The crewman paused, looking like he needed to get going.

“So we almost?” I started to ask, but then trailed off.

He didn’t answer my question, but I could see the answer in his eyes as he stared back. They said, “Nearly so.”

I smiled and thanked the crewman for a job well done, not really knowing or caring what he’d done personally. I thanked my lucky stars for being alive and cursed Egypt Air for its probable failure to properly maintain the old aircraft.

It was late morning, but unnervingly a brand new day and a new life. I wondered what might happen next.

Eventually, I bought a large piece of Egyptian peanut brittle and sat down in the sun to savor my earthly continuity. It was delicious and I bit off pieces slowly while hanging my feet over a high concrete retaining wall with a view over the airstrip. I had time to relax and to consider things before boarding the next Egypt Air substitute flight. In my renewed lightness of being, chewing away atop the wall, a pea-sized stone in the brittle broke off the tip of my eyetooth.

“What the fuck?” I murmured, then delicately touched what was left of the sheared-off tooth.

Damn!

Then—suddenly—I smiled to myself. That was a flick on the ear, I figured—from god, or Osiris, or Karma, or some other thing. A flick that merely said, “Don’t be too self-assured with yourself. You were just spared yet again.”

Wow, my friend… You have had some ADVENTURES! I’d never heard this one, or I would certainly have remembered,. So well told I’m afraid I’ll remember it as one of my own!