Marianique refused to stay an extra day in Ghorepani—despite our aching bodies, the eclectic collection of travelers, and the extraordinary views of the surrounding mountains. I didn’t want to leave. But she was relentless. At her insistence—conveyed as a curt “We go!” directive pulled from her little book of French-English translations—we were up at 5:00 AM and packing. It was the morning of our fourth day out from Pokhara.

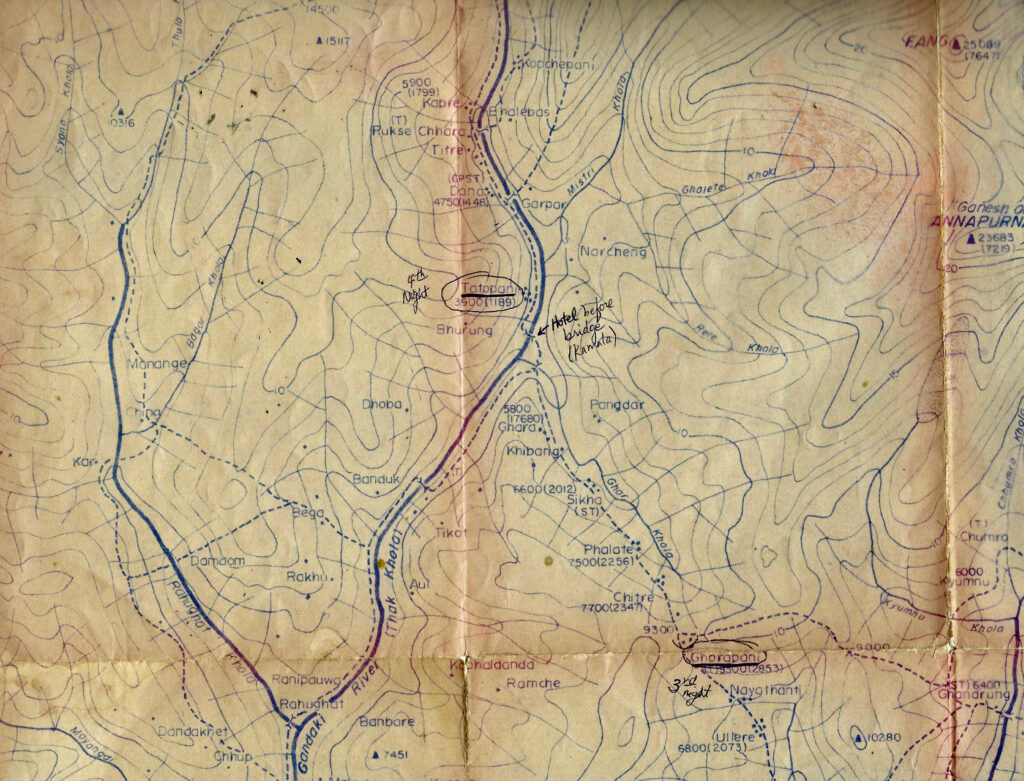

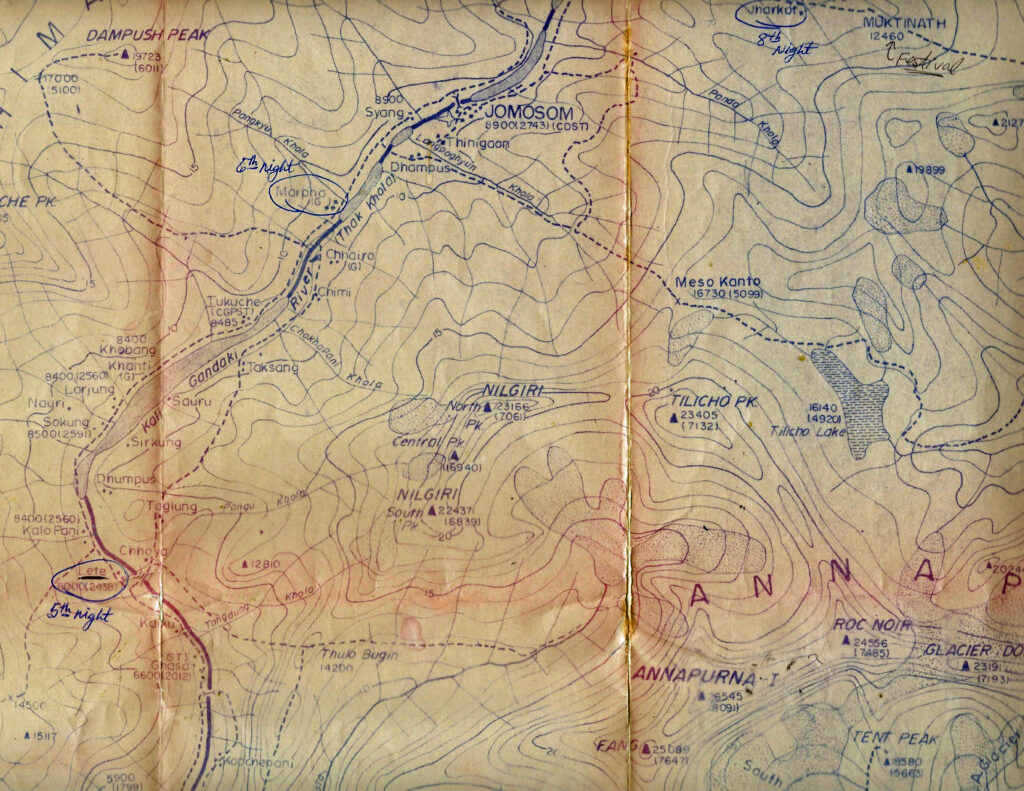

Shivering in the night-chilled air of the previous day’s thunderstorms, I opened my map to see the day’s route and mileage: 10.5 miles to Tatopani and a drop of 5,400 feet. Crap! We would lose all the elevation gains of the previous two days. My feet were not going to like this. I decided to stay in my blue Sauconys, lest my leather boots grind my toes apart.

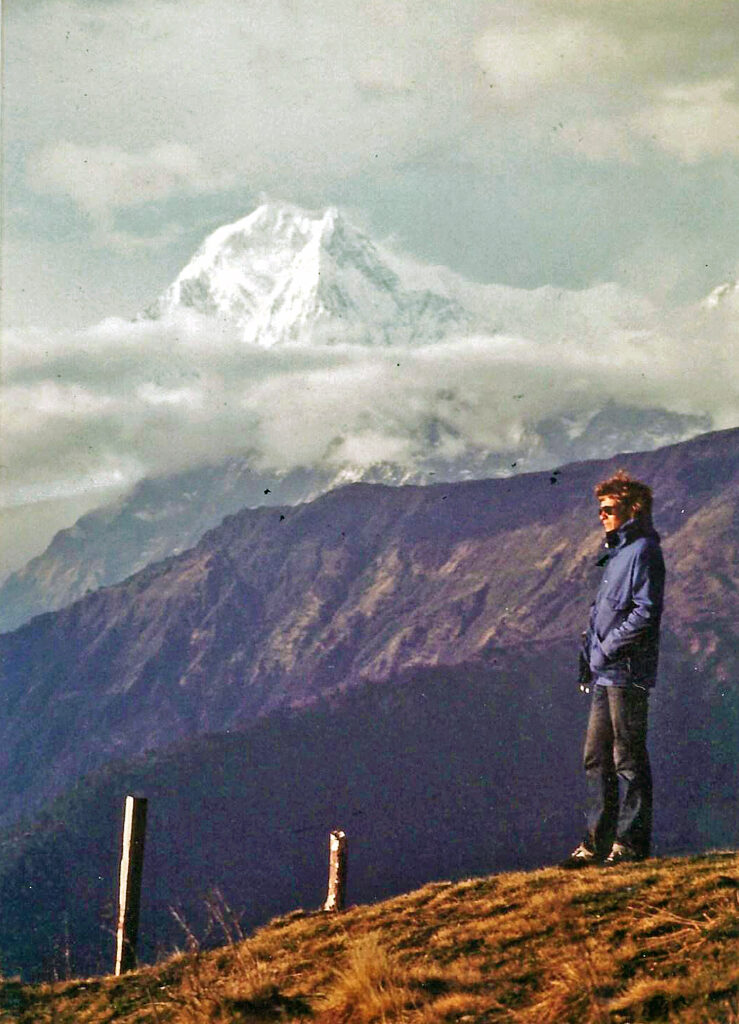

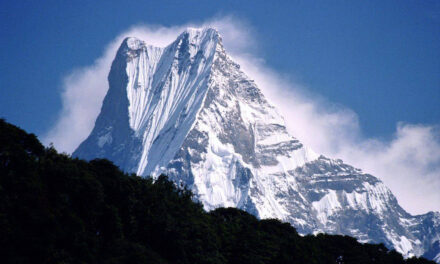

Even more ridiculous than our arising at that ungodly hour, the two English friends we met in the Lodge coaxed me into making an early 1,100-foot sprint to the top of the scenic Poon Hill, which looms above the village at 10,500 feet. Before breakfast. That place had been talked about and its views heavily photographed. Consisting of a round grass-covered knoll surrounded by forests, it’s a natural observation point, a geographic protrusion on a ridge with unobstructed views of the Annapurna and Dhaulagiri massifs.

*

Several of us set out before the other trekkers were awake for a gasping part-run part-walk up a narrow trail to see the sun make its first presence between the peaks. We reached the top with pounding heads and heaving chests.

The round grassy hilltop reminded me of the surreal “Hills are Alive” opening scene in Sound of Music. But it was far more than that. The towering peaks above us rose another ten-to-fifteen thousand feet, beyond the clouds to a vertical world of ice-caps and hanging seracs. Around and below us were the red and pink treetops of the rhododendron forests catching the first rays of daylight. The Himalayan wall stretched east and west into the distance, seemingly forever. Well below their wooded flanks were scattered villages and sculpted farming terraces. Poon Hill wasn’t just a grassy knoll; it was a rampart of a vast rocky castle.

Our frigid group of scruffy tourists stood together silently, as we might have done in a great European cathedral with ornate apses, stained glass, and a pipe organ blasting, trying to take it all in. Please, brain, I thought to myself, don’t ever forget what you’re witnessing.

*

The descending trail from Ghorepani meandered northward through one small mountain community after the other, down through the rhododendron forest zone, then next to fields cleared for farming, and finally back to the lands of paddocked water buffalo and rice paddies. Aware that we had to make up all of our elevation losses, I winced at every crossing of a topographic line on my map.

In Sikha, a trailside village of some two-dozen houses and a couple of travelers’ inns, our path was blocked by a large crowd of Nepalese. Something was wrong and it was registered on the villagers’ faces. As we walked closer, a man looked up and approached us, then asked in very poor English if we were doctors and if we had medicine? We both shook our heads indicating, “No.”

Perhaps because we looked western and helpful, we were led through the crowd to where two men lay next to each other on the dirt. A few of the elders were squatting next to them.

From my first impression, the men were dead. Then one of them moved; a twitch. The men were in agony–it was painted on their sweaty, contorted faces. Pools of vomit surrounded them. Their complexions were grayish and, if actually alive, they didn’t look long for life. In broken English, one bystander suggested that they had been poisoned. Marianique and I looked at each other helplessly.

The faces of the surrounding crowd were taut with lines of apprehension and fear. These two men were probably known to them all, likely fathers or farmers of the village or perhaps local travelers. I looked for their large Nepali packs but didn’t see any. The loss of two men from such a small community would undoubtedly be a blow to everyone. I assumed these villages were all extended families. Seemingly there was nothing anyone could do.

Then an idea came to me. I dug into my pack and retrieved several black, foil-wrapped, activated charcoal tablets that Grant had given me in India. The large pills had successfully rid me of stomach sickness twice. But for blackening my teeth, they had no independent ill effects. Their containers confirmed that they were just carbon: absorbers of bad stuff. So I offered them up.

The villagers looked at the pills skeptically and then at me. Two elders advocated their immediate ingestion and coaxed the men to eat them. Some of the women adamantly resisted the idea of putting little black tablets down their throats. They pointed at me with wagging fingers as if I were offering something evil. But the sick men refused anything–they were too far gone. They just stared vacantly into the dirt, sweating, drooling, and dying. We stood by helplessly.

I wondered what might happen if the men ate the tablets and died anyway. Would we then be accused as murderers? Foreign sorcerers? Neither of us could explain the inherent harmlessness of activated charcoal in the Nepalese tongue. None of the villagers spoke English fluently enough to understand my vocalization of the words on the packaging. It was another conversational impasse.

Marianique must have had the same thought as me, for she soon pulled at me to put the scene behind us and move along. She nodded toward the trail with a worried expression. I agreed. We wished them well and stomped off.

*

Farther down the trail, we stopped at a tea house so that Marianique could have a bit of fluid for her empty stomach. She’d been sick at Ghorepani and couldn’t eat yet. Sitting on a porch with a view of the snow-capped Annapurnas, we took off our shoes for a session of blister control. I bought a 10-cent liter of chi, another of many substitutes for all the questionable water. Water buffalo grazed in surrounding terraced fields below blooming Rhododendron forests. A Nepalese woman served us a tin of cornbread.

We were still stunned by the dying men, yet simultaneously awestruck by the surrounding paradise. It was a paradise to us–perhaps not to the two men. To them, without purified food or medical care, maybe it was just an ongoing struggle. But then, any paradise demands a price; either the high cost to get there, or the danger to make it one’s home. I wondered what I’d do if I became deathly sick or poisoned so many miles from the nearest road. Die, I guess.

Wandering inside for more cornbread, I noticed that the inn’s kitchen had a dirt floor. Blackened cooking utensils rested precariously upon smoky wood coals. The tea I was to be refilled with looked like it may or may not have been boiled. Black things floated in it. The robed Nepalese women who served us squatted over the fire-oven with a dirty, naked baby at her feet. The baby’s nose was running down its face and dripping onto the mother’s toes. A fossilized grandmother crouched in the corn of the hut watching me, armed crossed. As I scrutinized the kitchen, both women looked up at me quizzically. I smiled and walked back out to the porch. It was best not to look into Nepalese kitchens.

And so it went.

*

We reached Tatopani late in the day, a picturesque riverside village where beaten trekkers basked in the sun, lounged in locally-crafted wooden chairs, and soaked in a thermal pool fed by a hot spring in the middle of town. The place looked like a primitive spa. I walked over and looked into the pool with at least twenty grubby trekkers soaking in its murky waters. Warm or not, I would not be submerging myself in that questionable bathwater.

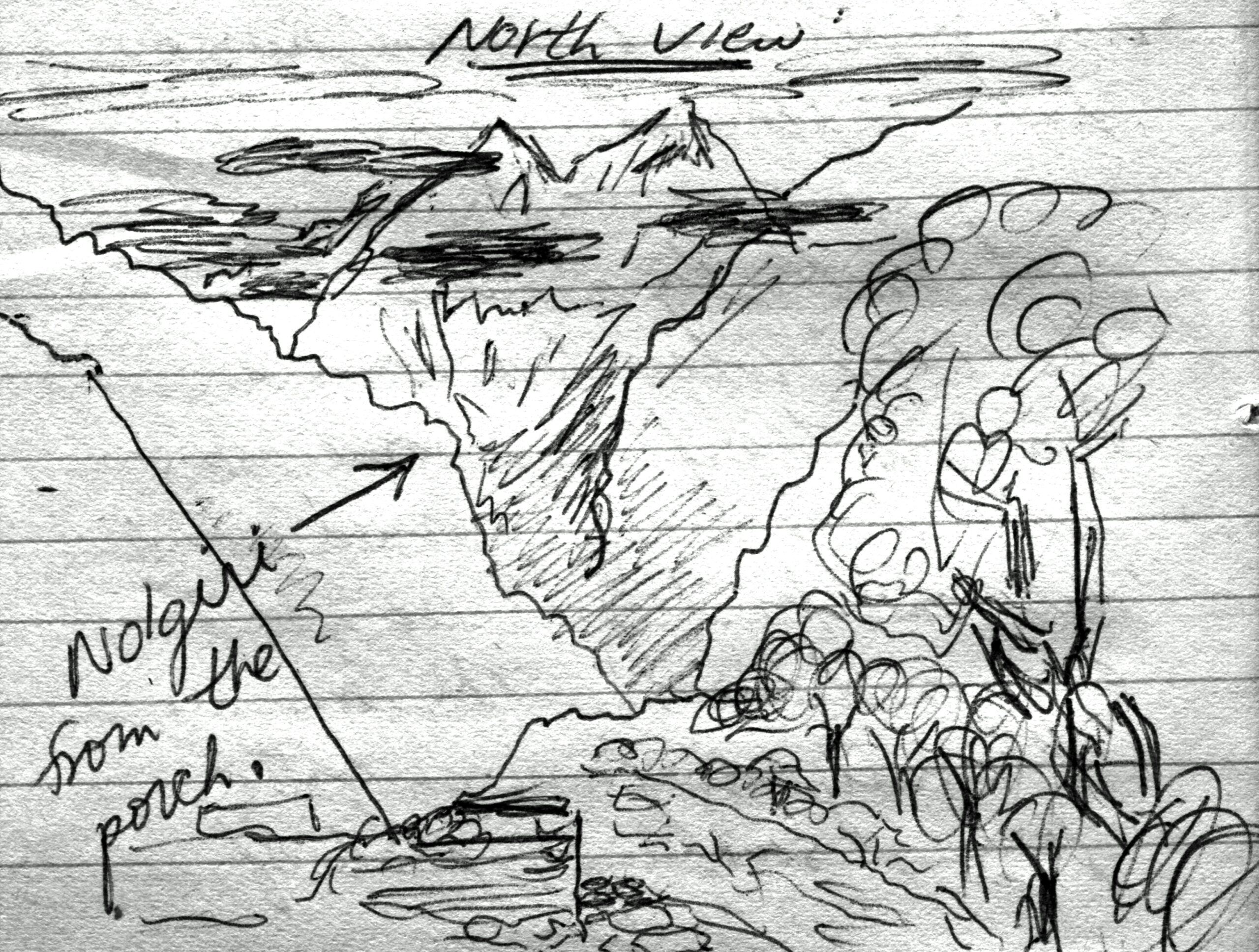

Our shared second-story room in the Tatopani Hotel—where separate beds were divided by a line and a sheet—looked out into giant bottlebrush bushes and lemon trees. From the inn’s main porch, one could relax with a table and chairs while observing the parade of exhausted trekkers entering town and dropping their packs, or simply hiking through. Around us, cliffs rose up thousands upon thousands of feet. I soaked it in. I tried to sketch it.

Tatopani offered local fruits, porridges, and pies, something I hadn’t yet seen on the trek. Not surprisingly, it was the turnaround place for many who had neither the time nor the stamina to continue onward, as well as for those who savored sleeping-in and luxuriating more than the long days required for the continuing trudge up to Muktinath.

Marianique was immediately turned off by the place.

In Tatopani one could be easily persuaded out of overdrive and into neutral. I lobbied for a day’s rest but was adamantly vetoed. Marianique would not be coaxed into lingering for even twenty-four hours in such a lazy atmosphere. The following day we left the river paradise early and pushed upwards. She was a step ahead of me—rising, eating, packing—and was waiting for me outside our trekkers’ tea house when I eventually joined her for the onward slog.

*

In our ascent up the Kali Gandaki canyon, we dehydrated ourselves while climbing thousands of feet toward the high ground of the mountain pass. We initially moved through bamboo thickets and terraced fields while dodging water buffalo and donkey trains. It was a long, hot trudge and the trailside foliage soon fell away to long stretches of unshaded rock. Tea shops thinned and I seriously considered drinking the unpurified water from the occasional steams we leaped across. But I didn’t. I imagined hidden upstream villages that washed in those streams, and whose animals urinated into them. Instead, I ate aspirin and held out for the inevitable tea vendor around the next corner; and we kept marching. No yellow eyes for me.

As we continued, the trail became more of a staircase: rock steps often more than a foot high. The experience was a bit like climbing a step machine in a sauna—not how I imagined walking up a Himalayan trail. Occasionally I went to all-fours for stability. Precipitous cliffs and drop-offs directly below our path imparted destabilizing vertigo; dangerous if one’s gaze wasn’t glued to the trail. I imagined stumbling on a step, while looking up at a peak, then pitching off into the abyss. Nobody would even see me vanish.

My feet were so sweltering in my blue Saucony running shoes that I longed to replace them with flip-flops. After all, the Nepalese all wore sandals and flip-flops. I grew up wearing them in Placerville—or going barefoot with toughened feet. I seriously thought about it. I’d had a tetanus shot a week before. But caution kept them affixed. Too many weird things on that trail.

We eventually rose above the exposed rock and heat and entered a dark forest that clung to the north-facing slope of our river valley where dripping deciduous branches draped with dangling moss shielded us from the sun. In the afternoon, clouds amassed overhead and it grew cool. When we momentarily stopped to don sweaters, there was a thrashing about in the high branches, then bark and other tree-bound objects rained down upon us. At first, we were perplexed. Then we realized it was monkeys. We’d become stationary targets in a simian arcade game. Every time we moved, the bombardiers above moved with us, throwing down debris and screaming down monkey laughter and insults.

We pushed on.

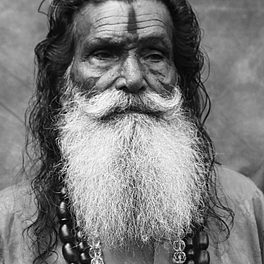

We passed an old sleeping Sadhu lying upon a great flat rock above the trail. He looked tired and restful in the coolness of the forest. Perhaps he was gathering his strength for the long high-altitude push to Muktinath, home of the eternal Hindu flame. The holy man had a long way to go. Turned out he was tired all right–dead tired. The big nap. I wondered if he’d rot or be eaten by ants before someone attended to his disposal.

We were now several thousand feet above Tatopani. The clouds continued to build above us and the air grew colder. Thunder echoed up the rocky canyons and lightning flashed, then a storm let loose and pelted us with rain. Marianique and I had ponchos for such weather but not much more. Beginning to get soaked through our meager coverings, and seeing no cover, we picked up our pace. There was nothing else to do. The village of Lete lay somewhere ahead of us, but we didn’t know how far since the trail was not marked with any “you’re-almost-there” signs.

We were beginning to shiver in the cold rain. I knew that drill, but we had neither tents nor stoves.

Then we spotted a village across the chasm we were traversing with a direct connection to our trail via a long swinging suspension bridge. The bridge’s superstructure was metal, which made me ponder such things as our getting hit by a bolt of lightning while crossing. It was that or be soaked and get hypothermic. Was it Lete that we saw on the other side? We didn’t know. The rain came down even harder. Damn! We opted for the bridge.

Martinique and I jiggled across the expanse, holding onto the suspended cables while being buffeted by wind and rain, a roaring river far below. Twice we had to stop because the bridge was swaying so radically with the two of us and our weighted packs that we thought it might flip over. We moved, quickening our pace, then slowing in fear, fast-and-slow in a jerky crossing, as the lightning flashed and the thunder cracked. Finally, off the wiggling expanse, we sprinted to the nearest village roofline and ducked under it. The building we sought had a worn “Trekkers Welcome” sign on the side facing the bridge, but this was hardly a lodge. It was a primitive stone hut with a tin roof.

As we stood wringing out our dripping outerwear and marveling at the ferocity of the storm, a Nepali woman poked her head out the “lodge” door, smiled, and beckoned us to come in out of the weather. We entered.

This place was indeed just a stone hut; a Spartan example of minimal habitability. But there was nothing else for us. The woman showed us where we would sleep: on two of seven cots, some in an extra room and others scattered about. There seemed to be room. But soon more soaked travelers came to the door and were also taken in. Eventually, eight of us jammed into the rocky walls with soggy hair and sloshing shoes. All of us had been accepted in cheerfully. I was not sure the woman was an innkeeper, or just a simple owner of a small house who wanted to make a little extra money. By that time, such concerns were irrelevant. The storm was still raging and the day was ending.

When night fell, the only light in the dark stone structure emanated from one candle and the flickering light of the wood-burning stove. Holes in its metal sides radiated yellow and orange light from the burning coals inside–a diorama of little suns. Wind whistled through the walls. Since only one pot could be heated at a time, the cooking process was slow. But that didn’t matter–we had nowhere else to go and nothing else to do. Lacking any exhaust pipe, the stove smoke simply drifted around us, then slowly wafted up to the ceiling and walls where it filtered out through cracks.

The trekkers ate first. We sat on the dirt floor while the woman prepared dinner and served it in little bowls; a meal of dahl and rice. Two kids with runny noses watched us silently from the shadows and the woman sang Nepalese tunes as she cooked, as if none of us were there. Our dirty dahl-stuffed faces reflected the dull, flickering orange from the coals. Corners of the house far from the meager flames sunk into blackness. While we ate, two baby yaks and some chickens meandered through the house, sniffing and stepping around our packs.

As we all settled into our sleeping bags for an early and uncomfortable night—there being nothing else to stay up for—I watched Marianique give up her cot to another traveler and then move to the rocky floor. Shit! I thought. I should do something. My brain and mouth refused to offer her any form of chivalry, however, and I soon nodded off on the knotted ropes of my ageless cot.

Totally absorbed by this Steve! The dead guys… the storm… the tension (natural, but not expressed outwardly) between you and Martinique, forced together by life — THIS doesn’t happen very often… What an interesting dynamic… The scenery… Wanting to remember Poon Hill, actually Everything, forever… Loving it…