Five uniformed Federales marched up the beach in our direction, eyes locked forward, guns in readied positions. Seeing them, our group stopped its rocket bombardments and stood frozen in the sand.

Damn! All at once, my exuberance was doused with a wave of stark, cold reality. We were screwed, busted, and might have only a short period of freedom before being taken away. So this was it.

Still, my brain resisted. We were certainly due for a reckoning, but what was the real issue here? I struggled to recollect all the possible reasons why they might be after us. Were these the Federales from Ensenada, having followed us north? Was it our excessive speeding on the highway? Had a concerned doctor from the medical center reported Mule’s disturbing injury to the authorities? Maybe it was a call from our recent victim in the restaurant? Or did someone at Art’s company report the missing van?

Paranoia swept over me. There were mere seconds before the Policia Federal stomped right up to us for a nasty confrontation. What to do? In my hand was a two-stage rocket with an explosive charge; in my other, matches. I could fire the missile off in their direction as a warning shot across their official bow—send them running while we fled. It was an amusing vision but probably a very bad idea.

*

We had converged in Newport Beach, a group of buddies, thirty-plus in age with college degrees and respectable jobs. Linked through backpacking, river rafting, and road trips, we’d all heeded the call for our overworked brain cells to let loose and twist to a higher frequency. Rod, Chris, and I had rallied from northern California; Art and Rick (“Mule”) came from the Southland.

Once joined together, the Equidon corporate van had ferried us southward on Interstate 5, high-speed and Mexico-bound, with each of us strapped into individualized captain seats. Those of us behind the driver rotated to-and-fro, engaging in multiple conversations, drinking bottled beer, and arguing over what cassette might be blared next. From the inside, we looked like a van of life-sized bobbleheads.

The van was “borrowed” from Art’s employer, a luxury transport reserved for Orange County executive commuting. It sported a wet bar, air-conditioning, surround-sound, and noise-suppressing wall-to-wall carpeting behind tinted windows. It was the perfect setup for our expedition across the border—our shuttlecraft to a foreign land. Equidon had no idea that the van was being absconded to Mexico, and nobody would ever know—unless, like Emelia Earhart’s Lockheed Electra, it came off its planned trajectory and crashed.

Our largest collective piece of luggage was the cooler, which was stuffed with two cases of beer, three bags of limes, and four bottles of tequila. We had transformed Equidon’s four-wheeled pride into a disheveled party bus. As the side door slammed behind me that morning, my brain told me that we all knew better than whatever we might be setting out to do.

*

As the van had departed our rendezvous place, purple cannabis was jammed into a deteriorated corncob pipe and ignited ceremoniously. The cabin soon filled with curling white smoke.

“Wait, wait, wait!” Rod had barked. “Shouldn’t we at least get onto the freeway before starting that?”

“Shud-up!” bellowed Mule from the front.

“On the freeway?” asked Chris. “That’s where one does this?” He laughed.

“No one can see in through these windows,” said Art from behind the wheel.

“We’re invisible!” Mule added.

Rod shook his head.

“Corona?” asked Chris. He held out an opened bottle.

I had never been in jail. Maybe this would be my big opportunity. That ponderous thought evoked a momentary wave of panic which amplified when the pipe reached my hands. After a mental adjustment, I decided I was being unreasonably paranoid and shrugged it off. To the outside world, I knew we were only another shiny metal box with four wheels, packed with sleeping commuters behind tinted glass. We were indeed invisible. Worry be damned.

*

We ventilated the passenger compartment at the Mexican border, hid the empty beer bottles, turned down the music, and smiled at the officials. The Border Control peeked in to see our pleasant faces, the van’s uncluttered floor, and then smiled back and waved us through. Art stomped on the accelerator and we roared south.

Through the streets of Tijuana, our wake left a roiling cloud of dust. If anyone were listening, they might have heard the deafening screams of Roger Daltry or Robert Plant, but the sound would have passed quickly. We weaved through chaotic streets and around pedestrians, lurched away from stray dogs, passed the bull-fighting ring on the edge of town, and then picked up the route toward Ensenada.

When Mule remarked how convenient it was that we could legally drink and drive south of the border, we opened another round of brews and toasted our host country. Who could imagine such behavior was legal? Soon empty bottles were rolling about the van floor and clanging into each other. I wondered about the truth of that assurance and I pondered the amenities of the Tijuana jails.

When the van pulled up to the Rosarito Beach Hotel, we piled out into a blinding sun. It was still before noon and the balmy air jolted us from the deep freeze of our smoky, air-conditioned Equidon den of iniquity. We stretched and promptly began pondering what to do next.

Art and Chris checked us in while the rest of us sat outside and enjoyed the radiant warmth. We were ready to swim, drink, lay back, and let seawater bake salt crystals onto our legs and arms—eager to be off the road.

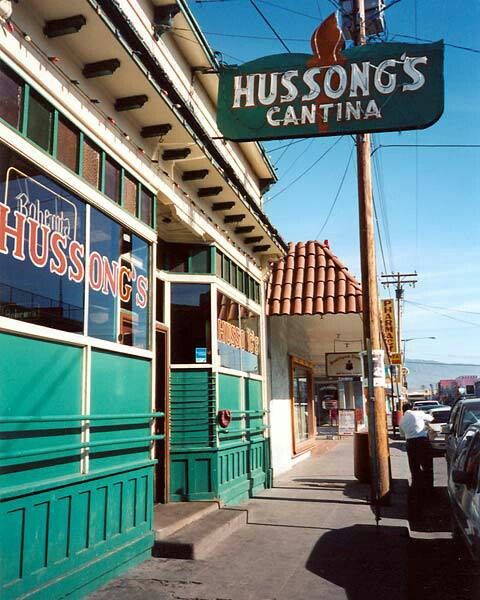

But the beach would be delayed as Art decided that we had a mandatory appointment with Hussong’s Cantina in Ensenada, a hundred miles south—a one-hour ride, at best. Art assured us that he would drive there safely. He planted a rosy vision of the notorious bar: good music, mariachis, frog curios, and talkative senoritas. He reminded us there were legal fireworks to be found in Ensenada. The group quickly agreed.

*

Buckled back in our seats, we spun out of the parking lot in a flurry of pebbles and were again hurtling southward on the two-lane highway. As the last tequila began to kick in, more beers were retrieved from the cooler.

Speeds above 90 miles per hour brought us down the bumpy tarmac faster than we had expected. We veered around farm tractors, goats, and a vehicle fixing a flat tire in the middle of our lane. Each obstacle was passed in a blur, our eyes briefly registering and our minds only fuzzily comprehending.

When we arrived, Art strategically parked the van in the Hussong’s lot, facing out as if for a quick getaway. The doors opened and we piled out into a pungent cloud of garbage and stale beer. I wondered if I could hold my breath until I made it through the tavern doors. Then I realized that Hussong’s likely smelled the same inside, so I just breathed it in as if I were pressurizing my ears for a deep dive.

We entered like a gang of western cowpokes stumbling into a nineteenth-century desert saloon.

The decrepit bar was sedate and filled with locals–no tourists. A collection of alcoholics and sunbaked workers eyed us skeptically and then returned to their quiet conversations. I panned around. In place of our imagined collection of senoritas were battered tables and chairs, dingy walls, unshaven faces, and a multitude of flies.

Crestfallen, we ordered up a round of tequila shots, chips, and beer—not to be undone by the place. But our presence was disruptive. The ambient noise level of the bar rose a magnitude with our arrival, so ours amped up to compensate. Chris threw some quarters into a jukebox that blared Mexican music.

Settled in for an uncertain stay, we drank and laughed. The more we drank, the noisier it became. Soon we were yelling. Rod periodically shrieked out for Chris to put Led Zeppelin on the jukebox. Slowly the calm bar we entered was transformed into an obnoxious din. Then, during the foggy chaos of our disruptiveness, several Mexican Federales barged in and stood, eyeing us suspiciously. The officers had guns and were not in a jovial mood.

The unpredictable nature of the Federales was notorious and I wondered what might trigger our first interaction. Maybe they were looking for an early morning shakedown. Perhaps the bartender had called them.

Oblivious to their scrutiny, Mule had gravitated to the bar where he was boisterously yakking it up with the bartender and some locals. Fact was, he was yelling and the Federales were closely watching him. The rest of us were doing nothing particularly obnoxious: but obnoxiousness is in the eye of the beholder.

Perhaps it was the way the Federales were behaving, or the way Mule had turned and glared back at them, but Art suddenly herded us all out of the bar. Once outside, he nervously commanded everyone to quickly get back into the van, which we did—oblivious to his reasons. Within seconds we were roaring away at breakneck speed, away from Hussong’s and the Federales. Had Art been drinking? I couldn’t remember.

“Time for fireworks!” Art barked from the driver’s seat. The next thirty minutes were spent at local fireworks vendors buying up everything that looked dangerous. The bigger, the better.

The return to Rosarito Beach was an uneventful speed race until it began to rain, whereupon the road transformed from a smooth Formula One racecourse to a backyard slip-and-slide. Several miles out of Ensenada, we came around a bend and confronted a mob of stopped motorists helplessly peering down at a truck that had slid off the pavement and rolled down a steep embankment. It was on its top, wheels still spinning, and from the expressions of men near the wreckage, someone was still inside and faring poorly.

We pondered stopping to help, although plenty of folks were at the scene. As we had slowed, Art reminded us that when the Policia eventually arrived, they would be asking many questions of everyone—especially us gringos. Beery-breathed Californians in a shiny corporate van might just be handy fall guys for the wreck and the damages.

Shall we stop?” Art inquired.

“Drive on,” came the reply.

By the time we arrived back in Rosarito Beach, we had seen three such overturned vehicles and all of us were ready to be done with Art’s speeding for the rest of the day. It was time to drink, smoke, and bodysurf–in that order. We stumbled out of the van, happy to have avoided the perils of our Ensenada venture, and set about locating the hotel’s bar.

*

Infused with additional “medication” and donned swimsuits, we hurried down the multitude of steps from our hotel rooms to the beach where we were greeted with warm water, clean sand, three-foot surf, blazing sun, and relative privacy. It was time for bliss.

As I waded out through knee-deep, then waist-deep surf, my head buzzing with the electric and numbing effect of several tequila shots, many beers, cannabis, and too much time in the Equidon van. I was ready for anything. I felt invincible; almost invisible.

Then something abrasive brushed my ankle. It immediately stung, and I picked my foot up out of the water to inspect it and feel it with my fingers. It wasn’t bleeding but was reddened. I wondered if there were jellyfish in the water that I hadn’t seen. I looked around, saw nothing, and decided the sensation was my alcohol-induced imagination—my near-invisibility to whatever bumped against me. So I ignored it.

Moments later, Mule muttered something unintelligible about a hundred feet before me, then crouched over at a grotesque angle. As he staggered around off-balance, I wondered how many more shots than the rest of us he might have consumed when I wasn’t looking. Rod moved over to where Mule stood and Mule fell into him, letting out a scream that overpowered the surf. He grabbed at his ankle and hopped around with a grimace that was either a death mask or a tequila-induced wince of laughter; it was hard to tell.

“Art!” I called out, then pointed to Mule.

Art quickly splashed over to Mule and, with Rod, stabilized him and then lifted him up, off his feet, carrying him free of the water. Once Mule’s legs were revealed, I saw blood spurt six feet into the air, followed by more red pulses from the bottom of his foot. It was a vision from a sci-fi horror movie.

Mule was rushed out of the water to the nearest beach chair, but he would not lie still. He was writhing and twisting like a snake and grimacing like he had been stabbed with a hot knife. So we picked him up again and carried him up the stairs. That was when I noticed he was crying–something none of us had ever witnessed.

Nobody knew Mule was capable of producing tears. He got his name for his Mule-like fortitude. Whining over pain was not in his nature, and crying was out of the question. We were stupified.

Art recognized that Mule had been impaled by a stingray. The barb had struck him directly in the ball of the foot where blood continued to pulse out. We all heard of the danger posed by rays, but none of us had any firsthand experiences, much less understand how Mule positioned himself for the tip of the ray’s tail to puncture the bottom of his foot. It was a mystery that made us quickly retreat from the surf.

In any case, nobody knew precisely what to do. We stood over Mule like confused doctors witnessing some alien virus that we knew nothing about. I shuddered at what must have brushed my ankle just before he was hit. What was the best course of action?

As Mule whimpered unintelligibly, it was decided that Art, Chris, and I would take him to the local hospital in the van—me, since I spoke a bit of Spanish, Art because he was the van’s keeper, and Chris because he could drive under any circumstance. Mule was rolled into the vehicle through the side door and we sped off to the General Hospital.

*

The emergency room was quiet when we entered, albeit for some whining child. In poor Spanish I was able to convey how the wound was occasioned, and where, and when, and how Mule needed an immediate painkiller for his aching “pie.” All the while Mule screamed, “Help me! HEEELP ME!!” to the entire hospital.

Our loud presence was not appreciated. Mule was quickly moved to an isolated room. Art, Chris, and I were directed to sit in a waiting room. I had several more conversations with various medical types, and then with a doctor who seemed to understand English clearly. This was a step forward, but when we asked for something to ease Mule’s pain, the doctor seemed not to understand. Perhaps he didn’t agree with that form of treatment. Or maybe the tequila and cannabis fumes were a bit telling—and he suspected that Mule was already adequately dosed with sedatives. What he administered was a big shot of penicillin.

“Ouch!” bellowed Mule. More expletives followed and many frowning faces were turned in our direction.

As boisterously as Mule cried for pain relief, his request continued unfulfilled. So we left the clinic about an hour after arriving, frustrated, and with Mule screaming “Get me away from these idiots!” at the top of his lungs.

Back at the hotel, we carried Mule to his hotel room and plopped him into a chair. He immediately leaned forward and grasped his leg, complaining of incessant throbbing. Out of medical options, we decided there was nothing to do but ply him with over-the-counter painkillers, making him chase the pills with more alcohol. He would have to tough it out.

Art thought a tub of cold water might be in order—a simple ‘take aspirin and soak your foot’ prescription—so we filled the tub and Mule obliged. He submerged his lower half in the water, looking ashen and feverish, and then began shivering. It was so difficult seeing him writhe and whimper that we discussed driving back to California for immediate medical attention. But, by that time, no one could safely drive anywhere so that option was out.

We concluded that stingray hits to the foot weren’t lethal–just painful. Thus, we would sit in the bar and await Mule’s eventual recovery since he had to recover eventually. The barb could only generate a finite amount of toxic pain. A selected emissary from the group would accompany Mule, talk to him, reassure him, help him drink beer and tequila shots, and be sure he didn’t drown in the tub. Hopefully, the tequila would warm him as he was immersed in the cold water.

I took one of the first rounds as Mule’s custodian. He didn’t say much, just held his leg, contorted, shuddered with spasms, and whimpered. I couldn’t even distract him. After what seemed like an eternity, without getting him to drink anything, I went back to the bar for my replacement and took another shot myself.

Chris succeeded in convincing Mule to take his elixir—after which Mule seemed more susceptible to the whole idea of a tequila treatment instead of a medical one. When Chris later returned with the story of that singular success, we cheered. It was surely a positive sign.

Each emissary reported on Mule’s progress, or lack thereof. Mule didn’t seem to be significantly improving and he was getting blood all over the bathroom. But he wasn’t getting any worse. Eventually, he breathed more steadily and didn’t spasm quite so much.

In the meantime, not having eaten all day, the rest of us found our way to the hotel’s restaurant.

Our presence in a restaurant was another bad idea, as we were then bordering on drunken disorderliness. A sizeable Mexican family was having a formal dinner at the adjacent table: grandma, the matriarch, sitting at one end of their table and the proud “Abuelo” at the other. They were nicely dressed and mannered: children and grandchildren wore embroidered white shirts and dresses; a civilized group—not like us.

Seated at our table, we plunged into a food orgy. Heads down, we barely acknowledged when Rod returned from the sick room to report uneventfully upon Mule’s condition. Mule was still alive—happily. So we kept eating and sent Art back in Rod’s place.

Art was gone perhaps only ten minutes when he reappeared to report that Mule was out of the tub and sleeping soundly, was no longer twitching, and seemed in no further need of observation. Relieved, our ravenous eating continued with a renewed, oblivious spirit.

Not until Mule walked in some forty minutes later and stood next to the table did I even raise my head. His sudden presence sent all of us into stunned incomprehension. We cheered raucously. The family next to us all turned their heads in startled horror.

Mule seated himself with the stumbling assistance of his disbelieving friends. It was a miracle. He had hobbled all the way from his room on his punctured foot without assistance. He explained that, once he had dozed off, he experienced vivid hallucinations about god, stingrays, and other such things. Later, he awoke with a start and the pain was completely gone as if the evil stingray spirit had just swum away. Now he wanted to eat. Another round of shots was ordered

Mule’s recovery electrified us and soon we were joking and carrying on as if the stingray had never interrupted the day. We were back on track and everything seemed rosy. Yet the day had become quite fuzzy. Was the rosiness a delusion? It was reassuring that we could still coexist in a restaurant next to a lovely family.

*

I’m not sure who flicked the bean across the table, but a garbanzo was expertly shot across our dwindling feast and into my face. A few moments later another bean glanced off my shoulder. That one came across the table directly from Chris, and his face betrayed the deed. Well, now: it was war.

It had always been my practice to retaliate with escalation. Without hesitation, I picked up a tortilla and flung it like a Frisbee in Chris’s direction. The tortilla flew true and landed on Chris’ shoulder. Our table roared. Not to be outdone, Chris promptly picked up a warm tortilla from a nearby basket, looked back at me half-crazed, then flung the disk hard in my direction.

The tortilla left Chris’s hand and floated upward and across our table, airborne, but not on a vector toward me. Instead, it rose up toward the ceiling, then momentarily stopped as if deciding where to go next. There it hovered like a UFO, spinning. Perhaps Chris had intended for the corn disk to circle the room and attack me from behind like a boomerang. It could have been on such a trajectory. But the tortilla then unexpectedly caught a lift from an HVAC duct and stayed aloft, still rotating, moving about if controlled by another force. It refused to descend as it slowly floated back and sailed right over our table.

The tortilla was, by then, beyond earthly control. It veered, swooped, wobbled, and only commenced an angled descent from its flight path when directly over the table of our Mexican neighbors. Then, like a stealthy cruise missile, it accelerated downward, arced, and landed with an inaudible plop on the head of the matronly Senora.

By the time the Senora realized what had happened, our entire table was in a state of heads-down, hand-over-mouth, teary-eyed snorting with uncontrollable fits and cackles. We had all witnessed the landing and were so affected that we could only try to hide our debilitating hilarity; to look away.

When I finally looked up, the lovely Senora was exiting the room–not to return. All of us were mortified. Yet none of us could muster enough control to communicate an apology. The more we contemplated what had just occurred, the funnier it became, until we finally realized we were in a complete state of intellectual and moral ruination. So we gave up trying to control ourselves and stormed out of the restaurant.

Stifling laughter, we ran to our rooms, shut the doors, and then let the outburst loose. We howled and cried and choked, whereupon we eventually concluded that we were such a threat to humanity that we should banish ourselves to the now-deserted stingray beach below the Hotel—to go back to where we couldn’t be seen or heard. There we could continue our venting away from innocent victims.

Grabbing our bags of recently purchased Mexican fireworks, we unleashed ourselves from the hotel rooms and ran back down the concrete steps to the sand. Although the sun had set, the waves reflected ethereal oranges and silver from the still-lit sky. We stood, momentarily, and admired the spectacle. In that beachy moment of ecstasy we might have collected ourselves and risen up from our heathenness. But we didn’t. If the concept of moderation was fleeting, it took that opportunity to completely flit away.

*

First, we lit the sparklers and hurled them at one another. Those made curious glowing lines as they spun and flipped through the darkening air, but that entertainment only lasted about ten minutes. Thereupon we grew tired of such child’s play and gravitated to the single-stage skyrockets.

The skyrockets required launch pads, so we placed empty beer bottles in the sand with necks aimed toward the sea and inserted the rockets with the fuses exposed. That made for forceful and directional takeoffs. Lighting single-stagers simultaneously, we launched waves of three and four, their timed charges exploding just before they plummeted into the surf. The beach sounded like the Fourth of July.

When our supply of single-stage rockets ran out, we pulled out the two-stagers. They looked like crude battlefield weaponry, being longer, fatter, and more formidable than the single-stagers. They sported descriptive warning labels with the words “Peligro” and images of exploding children. I suppose the labels should have given us pause.

The first of these two-stagers roared upward from its bottle, going a hundred feet higher than any of the single-stagers on its initial burn. When the second stage fired to life, it flashed a long yellow flame and charged up to a great height whereupon it was blown apart: BOOM! We all stood agape and in awe, as the report echoed up and down the beach.

As it became dark, aiming became more a matter of guesswork. We knew there was sand and cliffs stretching north and south from where we stood, but that became less visible in late dusk. However, the luminous exhaust of the first two-stager had lit the sky and revealed rows of houses perched south of us on a headland. Those looked most interesting under the rocket light. Interesting and inviting.

The next rocket was sent in a southerly direction toward the sea cliffs, but it lacked altitude and crashed onto the beach before the second stage ignited. It fizzled in its sandy crater and exploded, a victim of a bad trajectory. We all sighed at the loss of such a fine missile.

A third rocket was launched toward the same cliffs, this time with a much steeper angle of trajectory. It quickly rose up two hundred feet, paused for the second stage ignition, and then resumed climbing. What we hadn’t counted on was the onshore breeze. As it rose, it drifted shoreward and soon was directly above the seaside houses on the bluff. When the second stage expired, the rocket fell to within a hundred feet of the tile rooftops before it exploded with a loud KABOOM! We were stunned at how much louder the retort sounded over the tile roofs. It echoed and reverberated like wartime artillery, an effect completely lacking over the water or above the sand.

We were awestruck. In short order, three more missiles were targeted over the southern bluff, all of which exploded noisily right over the rooftops. KABOOM, KABOOM, KABOOM! The effect was stunning—as if we were engaged in a glorious battle against a foe that dared not show its face.

As we were preparing yet more rockets, Mule called out sharply to the rest of us, “Guys! GUYS! FEDERALES!” He wanted our attention quickly and his voice sounded tense. I looked up to see five Mexican Federal Police officers approaching us with flashlights along the beach from the south. They came from the vicinity where our bombs were bursting-in-the air above the rooftops. I stood up, still holding my rocket and matches.

*

The uniformed official leading the pack walked toward us with a confident stride, a steely handgun in his holster. He looked agitated. Four accompanying soldiers, all helmeted, carried automatic rifles off the shoulder straps and in ready positions, with ammunition clips locked in place. They looked stern.

This wasn’t good.

Images of Mexican prisons flooded my mind—again. They were bad visions; places of rusty steel bars, communal toilets, and cockroaches. These guys might not be our jailors, but perhaps our torturers or executioners. As they approached more closely, their eyes betrayed that they didn’t like us one bit.

Calmly but forcefully, hoping the Federales didn’t speak English, I called out to my cohorts: “Don’t anybody run and, whatever you do, don’t laugh. Let me do the talking.”

My friends stood still silently, like a petrified forest.

I smiled and raised a hand to the comandante as he approached, then cheerfully pronounced, “Hola senor!” and “Hay algun problema?”

He nodded and jabbered something in Spanish while pointing at the fireworks and waving his hand in the air.

Shit! I thought. What did he say? My Spanish pronunciation was far better than my conversational comprehension.

I nodded back with attentive concern, understanding his thrust while not understanding his words, wondering if I was betraying my drunkenness, worried that our pot-reeking presence was drifting his way, and curious whether my cohorts were controlling their snickering. It was a delicate moment.

In broken Spanish, I stated that we had purchased “los skyrockets Mexicanos” in Ensenada, that we were only shooting them over the “oceano” and that they were “muy magnifico!” As I spoke, I noted that Art was standing in the gloom and shaking his head at me, a smirk on his face. To the official, I exuded admiration for Mexico, awe at our legally-purchased toys, and added as much cheerful diversion as I could muster. “Los son legal, no?”

The commandant shook his head and pointed at the houses on the bluff, indicating that which brought them to the beach—the explosions. The “personas” in the “casas” had complained. Furthermore, what we were doing was “ilegal,” “malo” and “muy peligro.”

I listened and nodded a lot with a very serious expression.

Ultimately I denied that we were shooting rockets at houses, motioning toward the sky, the wind, and noting its unfortunate on-shore “direccion.” All the while the small army kept us surrounded. I then asked if they would like to have all of our skyrockets and remaining sparklers. We only had a few left, so I figured that shouldn’t cause us too much grief. The commandant indicated that they would, indeed, like the fireworks and that we should then go back to our hotel.

“No problema,” I responded. There was much nodding among our little group.

All of us gringos understood our situation and obligingly handed over the missiles as we vacated the beach. The Federales watched us suspiciously as we skulked back up the stairway to the hotel. At the top of the seaside veranda we stopped, partly to appreciate getting through another close call, and partly to muse over our spontaneous diplomacy. Then we pondered what to do next.

Lacking a better plan, we filed into the hotel bar for one last round. Mule thought there might be some senoritas there, but luckliy the bar was empty of senoritas or anyone else we might further offend so we collectively decided it might be best to just turn in for the night. Nobody even had to suggest it—we knew.

*

Within our stifling rooms, we lacked a sufficient supply of aspirin to ward off the nighttime tequila sweats and headaches. So it was that we awoke, one after the other, to raging brains and feverishness. Cold showers were the only way to drop our core temperature and to wash away the tequila as it oozed its way back out of our pores. It was a dismal affair.

Of course, showers meant water fights so, by the end of the night, we lay in beds soaked completely through.

Dawn and checkout arrived much too soon. We donned dark glasses and slunk around sloth-like, realizing that what we really wanted was an American breakfast.

It was no surprise to anyone that our weekend in Mexico became abbreviated as suddenly as it had begun. Past experiences had proven there were times when it was simply better to flee than to stand one’s ground—lest some detractor orchestrate a retaliatory ambush or arrest.

We left Rosarito Beach spinning gravel as we left the parking lot and roared away in the air-conditioned van, aiming for the border. There was still no pause. Inside the van, we blasted the same disquieting music as we did on the trip southward the day before while finishing up the remaining beer supply behind our tinted glass.

In twenty-four hours’ time, five of us had little to show for ourselves, other than poisoning our livers, priming Mule for several future medical procedures, and leaving poor impressions on many of our southerly neighbors. The tequila was consumed, the skyrockets launched and confiscated, and the corncob pipe chucked out the window before the border. As we crossed back into California in rumpled clothes and grimy hair, drained of our playthings, we gave a collective sigh of relief. We were home intact—not incarcerated. We were blessed.

Well; one of us was less blessed, as he came home with a case of crab lice. That might have made for a particularly lascivious story if it weren’t simply the result of the unwashed and bug-infested hotel bed in which he slept.