“Did you bring the Dramamine?”

Chris dug into his backpack, rummaged around, then looked up with a blank stare. “You mean YOU don’t have it?” he asked.

“No.”

He shrugged and sighed.

“Shit!” I replied, immediately devastated. “It must be in the room on the table, in the pile that got tossed in a heap when we came back from Señor Frog’s.” I tried to recall if our return was actually last night—or early this very morning—or some other night. My brain needed more coffee. I rubbed my face.

“Damn-it! Where can we get some caffeine?”

We looked around at the line of tourists forming at the dock. The Yelapa Beach ferry was not yet open for boarding, but its capacity appeared limited. It was smallish and probably lacked a shop that dispensed sea sickness tablets. Maybe there would be coffee aboard. But coffee might not be the best idea at sea.

In back of us were a few old metal warehouses—nothing in the way of a store. It was too early for a store to be open anyway. So we were doomed. We hadn’t the time to venture out without missing the departure.

The last time I ventured out on the ocean—actually the last few times—I had spent most of the voyages leaning over the rail, green and heaving, wanting to die. I wondered if the “45 minute” travel time on the brochure was accurate. We were in Mexico. It might be longer—considerably so. Moreover, the sea seemed to be rolling.

“Maybe we should go tomorrow,” I volunteered. I knew that wouldn’t work with our schedule. Today was the only day. And, I wanted to see the iguanas we’d heard about.

Chris looked at me pathetically, concerned for his own well-being as well, then rummaged back into his pack again for several moments, going through all the pockets. Then he pulled out a bottle—a plastic one with a prescription label wrapped around the side. “Maybe this will work,” he ventured.

“What is it?”

“Valium; for my inflammatory arthritis,” he answered. “Full bottle.”

We just looked at one another.

*

We washed down the first Valium tablets with warm Tecates, still waiting in the growing line at the docks. Beer seemed a bit early, given the lingering haze from the previous night’s activities, but we’d forgotten our water bottles too. So we had to plunder our afternoon refreshments—in deference to the rolling seas. Beer and valium. My mother had said things about people who mixed these things.

Twenty minutes later, cast off and underway, the swells grew and the boat pitched. Growing a little queasy at the mere thought of the persistent motion, we studied the prescription to be sure we weren’t exceeding any medically prescribed limits; seemingly we weren’t. Yet both of us were feeling skittish. Then, knowing how doctors typically under-prescribe, we each took another.

“How much alcohol can you drink with Valium before there’s a problem? “ I asked.

“A problem?” Chris responded incredulously. “How should I know?”

“Well, it’s your prescription!” I jabbed. “You should know.”

Chris looked back at the bottle. He took off his glasses and squinted, revealing bloodshot eyes that might frighten an ophthalmologist. “It recommends here at least two beers per dosage. And we’ve taken two pills—I think. So that’s four beers—each.”

“So we can safely have another one now?”

“Shit!” Chris looked at me and snickered.

*

When an anxious tourist called out that Yelapa Beach could be seen in the distance, I lifted myself up from the forward gunnel, over which I was dangling, and took a look. It was there all right, way out in the distance, shimmering. I rubbed my eyes. The pitching had nearly put me to sleep.

Once on board, Chris and I had drifted in different directions. He went up to the top deck, where swivel chairs commanded a wide view of the seas and the coast. Top deck was full of chatting folks in love with the idea of a voyage on the ocean. I made my way to a less populated part of the lower deck, close to the rail where I was relatively certain I’d be heaving in short order. There I’d planted myself, keeping my eyes on the horizon, hoping for miracles.

Then our medications began to take hold.

The porpoises in the water under the prow quickly caught my attention, so I’d moved all the way forward and made my place right above to spectate and commune with them. So playful they were. It was as if they were trying to wink at the humans. I did my best to get close to their space in the bow wave. I imagined surfing right alongside them. Some made those odd squeaking noises when they sprang out of the sea beneath me.

As I lay there looking down, the ship plunged over swells; crashing, splashing and foaming as it went. The water was five feet from my face, then twenty, then five again, up and down. It felt like I was five years old, back on the big beach swings in the sand at Hermosa Beach. Up and down, over and over.

A porpoise reappeared directly below, turned its head as it slid down the bow wave, and looked up at me. I turned my head and presented one eye back to it, then winked. “Hey, down there!” I called out. It squeaked back.

“Hey Dad!” came a voice from behind me.

I pulled myself up and looked around to see a young kid pointing at me and seemingly beckoning his parents to come over. He’d apparently heard my attempted communications with the finned-mammals below. One parent came over, sized up the situation, and promptly removed the child a safe distance away, eyeing me with suspicion. The parent, a middle-aged man, seemed to shimmer just like the beach had. Maybe he was a mirage. I regarded him as such.

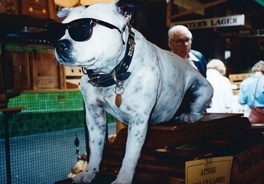

That’s when I’d realized that I hadn’t heard from Chris since we boarded. Startled, needing to confirm that he was still on the boat, I stood up and peered around. I spotted him a level above me in a swiveling captain’s chair, pitching with the ship, spinning around, gabbing to the surrounding tourists, and to the air itself, holding a beer in his hand, wearing a jug hat and veiled behind his coke-bottle dark glasses. He was all smiles and white teeth. If he was a canary in our rather medicated coal mine, then he was doing just fine.

Feeling more assured, I draped myself back over the forward gunnel at the bow and rejoined the porpoises, up and down, up and down, dangling blissfully and occasionally getting slapped by sea foam, until we docked.

Thanks to our creative self-prescribing, the sea never sank its teeth into either of us.

*

Suddenly we were at our destination. We found ourselves disembarked and standing on the warm, soft sand of a lovely playa surrounded with palm trees: Yelapa Beach. There was a bar serving tropical drinks, large colorful birds on perches, Mexican women and kids wandering about selling all sorts of stuff, and horses offering rides—a regular circus.

“Where to?” I inquired. “And where are the iguanas?”

Chris stood in front of me with his hands on his hips, then replied, “I neglected to tell you one of the instructions from my prescription.” He pulled out the bottle from his pocket and moved it close to his face.

“What’s that?”

“It says here, in the fine print, to have a tequila popper at any palapa of choice.”

“Uh-huh.”

We moved across the sand to the official looking Yelapa Bar under the shade of a palm and then engaged the English-speaking bartender. He seemed happy to see customers. I looked around for iguanas, but didn’t see any. That was a little depressing. We’d come all that way. Perhaps a popper might be good advice.

Soon, with Chris’s generosity, there were poppers all around. A few other locals joined in. Then it became a little excessive. I lost track of the rounds, and then of time. All the while, tourists drifted about, ogling at the south-of-the-border spectacle by the water. Families too, although they gave those of us hiked up to the Yelapa Bar a wide margin. It was one group sizing up another. Chis and I took it all in under the shade and even made some new amigos. Happily, one of our new cohorts seemed to know where we could find the iguanas.

“Donde estan los iguanas?” I asked.

“We will find one for you,” came the response.

“Great!” I sat, then lay down in the warm sand to wait and promptly dozed off.

*

Dreams overtook me on my Mexican sand chaise. I was melted wax. Eyes closed, my mind went from one place to another.

All was bliss until the dreams took on a twist I didn’t expect—a nightmare from my childhood. It was Godzilla. And the beast was after me—as usual.

This was a repetition of my collection of fears. Odd, since I’d vanquished the beast years before (that’s another story). But here he was: massive claws and teeth; hot breath; scaly spine up the back; flared nostrils tasting the air. He was sensing my presence, clomping after me when I ran, coming to corner me.

“whaaarrgggg!” I bellowed, opening one eye.

He was still there, for real, motionless for the moment, staring me down. I couldn’t look away. It was over.

But then, something was wrong. This monster had four legs.

*

Laughter brought me back to my senses—numbed as they were. I squinted open both my dozy eyes, noting I was still on my sand bed, but now covered in the stuff up to my neck. I gazed around. Multiple sets of legs surrounded me like a sparse forest of trees.

“Wha?” I managed to mutter.

“Mira!” came a voice from above. A finger pointed down, at me.

I panned up at laughing faces, and then followed the finger. There upon my chest was my Godzilla, with four claw-clad feet, spiny back and a long tail. It was staring at me the way the monster had so many times before in my childhood nightmares just before tearing me to shreds. There were teeth too; sharp ones.

But it wasn’t the monstrous beast at all. It was my Iguana—and happily much, much smaller than the real Godzilla.

“Argh!” I managed, unable to lurch back since I was half-buried in the beach. Who did that?”

“Tu Iguana!” came the response.

I could hear Chris laughing in the background.