Standing alone in the middle of a dirt-floored, fly-infested local marketplace, it didn’t register that there were no other tourists within sight or earshot. Why should it? This was one of my impulsive plunges into Indian village life; a meandering trek by rickshaw, by a long trudge down a busy pot-holed street, and then through the beckoning maw of an old two-story building with a variety of interesting signs on the front. A wholly un-tethered exploration. It was all predictably adventuresome—and then, suddenly, it was not.

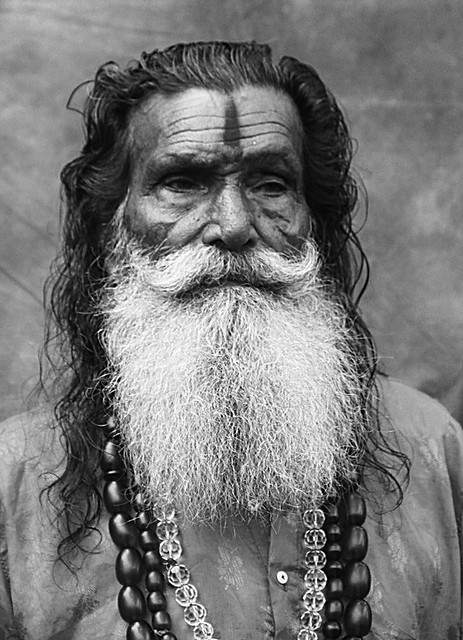

No sooner had my eyes become accustomed to the crowded darkness of the covered bazaar, and my focus trained upon some interesting local goods, than I was grabbed and restrained, and just as quickly surrounded by a circular wall of tensely curious townsfolk. They stared at me, immobilized in the vice-like clutch of an old Sadhu who was both taller and stronger than me. In fact, he towered over me. He looked like Lurch in robes, with a painted face, beard, long scraggly hair, skin the dark color of the earth, and what appeared to be the staff of Moses.

I stood transfixed: there was no wingman; no backup. If I had to be found, I’d be a needle in an Indian haystack.

The Sadhu had swooped in from nowhere, like a bird of prey. He must have seen me fumbling with my wallet. He grabbed my forearm and confronted me in the milling crowd. As he held on, the long index finger of the hand clutching his staff pointed assertively at the wallet in a jabbing motion. At the same time, his eyes stabbed into me. My wallet was held precariously in the very hand in his control. He clearly wanted it—or its contents. He barked a command in Hindi, and I understood him clearly; but I didn’t know a word of his language.

I pulled hard against his grip. He held fast. I yanked. Nothing. There was a murmur among the gathering crowd, who all stepped forward in unison. When I reached for the wallet with my free hand, the Sadhu blocked it. Then he raised the staff as if to bring it down on me.

I had merely been peering into my wallet’s folds to extract some rupees for a purchase, doing some mental calculations in the process. Not paying attention, I guess. The Sadhu had seen an inattentive target; a tourist with money. Then he had me and I wasn’t going anywhere.

“Shit!” I mumbled to myself. This is how dumb tourists disappear in foreign countries.

My mind floundered with logic. Taking stock of my “reserves” before a marketplace purchase, making sure there was still enough cash remaining for lunch, seemed like a reasonable exercise. Any purchaser did this. As I stood looking downward at my loot, engaged in calculations, the Sadhu had rushed up, reached out and grabbed onto me. Startled, I looked up into the face of a giant. The situation wasn’t pretty.

Moments ticked by. The painted Sadhu stared at me; into me. “What will you do now?” he silently asked.

Someone in the crowd jeered in Hindi. More followed suit. Whose side were they on?

My heart raced as I panned around and considered my options. There were thirty or more people surrounding us. Some of them held wooden staffs and canes, as well: would-be weapons if things got out of hand. They formed a wall around me.

*

Sadhus could be unpredictable by my estimation. For the most part, they just drifted about wearing colorful paints and white robes—robes that could be mere loincloths. They meditated, begged for offerings, and were provided sustenance by the population. As holy men, Indian people heeded and respected them—that was my observation, anyway. While dependent upon handouts, Sadhus renounced the material life to concentrate, instead, on reaching a higher, holier state of being.

Sadhus could also have an occasional, albeit infrequent, habit of confrontation. They could flip from complete serenity to hostility in a second. Maybe we all can.

As a rule, in a foreign country one respects and abides by the social mores of that place. That’s just being a responsible world citizen. It’s also the recognition that when in Rome, one does as the Romans. One has to be aware and respectful, never acting arrogant or elitist. I thought I knew that. Well—what did I really know? Foolishness was not out of my realm. Still, I’d never confronted a Sadhu’s wrath.

*

At first I was petrified. Shaking my head in protest, I tried to back away, but his grip was solid. His hand remained attached to me and his feet remained planted. I couldn’t even pull him from the position where he stood. Less than a minute had passed, yet I felt traumatized for an eternity. My emotions reeled and my forearm smarted from multiple failed attempts to pull away.

The surrounding crowd was suddenly larger, louder and feeling more like an assembling mob. They were watching the confrontation and closing in. Some were yelling and pointing at me with the same jabbing fingers as the Sadhu. The big holy man held me firm.

My brain raced. I’d been stupid to open my wallet in a public place. That was probably like driving a Ferrari around in the slums—a conspicuous flaunting of wealth. Boorish to say the least. I loathed such behavior in my own world. So I understood them. It was my error.

Should I offer him my cash? That thought rushed over me too. So did the vision of all the other hands that might follow his—hands of those who saw weakness, and were in need. This was not my world, after all. Yet, maybe it was in a way.

Trouble was, I didn’t feel that my cultural lapse and delayed awareness was grounds for some vindictive financial or physical punishment. My lesson was already learned; clearly and quickly. I may have been “in Rome,” but I wasn’t getting mugged.

*

The multitude of poor in India was overwhelming when I was there. Despite the country’s purported progress, the poverty was staggering to the mind. The destitute were everywhere. They clogged the trains, the streets, the shops. There was always a line, a crush, a mob or a “queue” as they call it. Children followed me with outstretched hands. Lines for trains and busses were human masses of pushing, shoving, and crowding. Among the throngs, there was little order.

It’s staggering to consider that India’s habitable geography is about one-third that of the US, while about four times the number of people live there. That’s ten to twelve times the density of the US population in the livable areas.

If anyone wants a glimpse of unrestrained population growth—whether the result of culture, governmental ineptitude or perceived right–one should go to India. There, or maybe China. Both are there to witness–to stare you back in the face. That’s the possible future for all of us.

*

My mind raced, then clicked—aided, perhaps, by a sudden, heavy internal wave of adrenaline. Clearly I need to break the impasse.

Remembering how I’d loosened the grips of my pursuers way back in El Dorado County flag-football days, I spun. I didn’t just spin, I whipped around with a vengeance, letting my arms be the flags and letting my legs do the spinning. A sudden whirling dervish, my arms came to me as I rotated like a cable spins to a spool with all the force of leveraged centrifugal momentum. I gyrated around two full 360-degree rotations and then, with loosened and unfettered freedom, stopped abruptly.

As if melted away, the welded-steel Sadhu hand and fingers were shed from my wrist. I landed facing my holy opponent, then planted my feet and stepped back. My wallet flashed into my front pocket leaving both hands free. I breathed in and stretched my arms around and above my head as if readying for a brawl. We faced each other. He was a biblical Goliath.

Promptly the crowd went silent and backed away, perhaps in shock at my unexpected move. Not sure why they did but it didn’t matter. I was now free, clearly agitated, and a good half-foot taller than all of them but for the Sadhu himself. Maybe they felt they couldn’t predict the wild mind of an unshackled westerner. Their petulant glares visibly melted away to that of wide-eyed concern. Maybe they were now pondering where the best exit might be from the impending mayhem.

I panned around. Several open gaps suddenly appeared between the onlookers as they all moved away. Quickly I looked back at him, keeping the threat in focus. His eyes met mine once more. Maybe it was my imagination, but I’m sure the Sadhu smirked at me, even smiled as if something different came over him the moment my fortune was transformed. His eyes said more than his mouth. It was as if he knew I had been treated to a lesson of some kind; a lesson delivered with an arrow’s penetration.

My thoughts cleaved. No way, I told myself. This was just an attempted mugging. Was it? Maybe not. Maybe the money didn’t matter.

Without waiting to sort out the mystery, I turned and strode through one of the gaps in the diminishing crowd, glaring at all who were still in my way and with the aim of knocking down anyone who might bar my way. The townsfolk got the message and moved aside and I was quickly out of the market and into the street. Into the safety of the light and sunshine.

The light and space felt liberating. I breathed and squinted at the sun. A large white cow ten feet away me looked over at me and chewed. Serenity took over once more.

My new freedom felt liberating yet oddly burdensome. Should I have given him something? Should I have dealt with the confrontation differently?

My head spun. How could I have reasoned with the man when spoke no Hindi? Then, realizing the conflicted lesson was mine to take away and savor, and without looking back, I picked up the pace and just kept moving. That “mistake” would only be made once.

One thing was clear, despite the suddenness and uncertainty of the event: I knew I’d been schooled–schooled by a Sadhu.