“ACTIVISTS TARGET DOG-MEAT FESTIVAL.”

That was a recent news headline from the SF Chronicle (see http://www.sfgate.com/world/article/Activists-target-dog-meat-festival-in-China-7227544.php). It was about the Chinese—how they eat dog meat. They eat everything. That was my cynical attitude, too, especially looking closely at the image of the rusty cage full of puppies next to the street merchants. Activists apparently sought to shut down this summer’s dog-meat-to-eat festival, to stop the slaughter and consumption of the puppies—kitties too.

That article left me simmering. I like dogs; even cats sometimes.

Later that very night, while reading the Indian adventure, Shantaram, I chanced upon a passage where a westerner pled for an Indian Hindu man to stop whacking his cart-pulling water buffalo with a board—a board with a nail in it. It wasn’t making the animal bleed or move particularly fast; it just made it move in the first place.

The westerner told the Indian that the “prodding” method was cruel.

The Hindu man confronted the westerner, saying it was less cruel than eating the animal (i.e., cattle) —which westerners do and Indians generally don’t.

The western man, predictably, then explained to him that western cattle were eaten “humanly.”

The Hindu man sneered.

Like many westerners, I too have an image of certain animals being of a higher order; intelligent and sophisticated—and that dogs are high and cows are low on that measure. I have a dog; she has the run of my house. Cats may have a little sophistication too. Maybe.

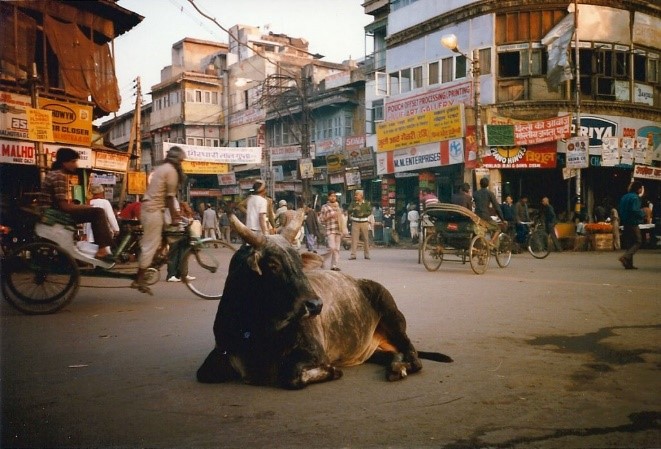

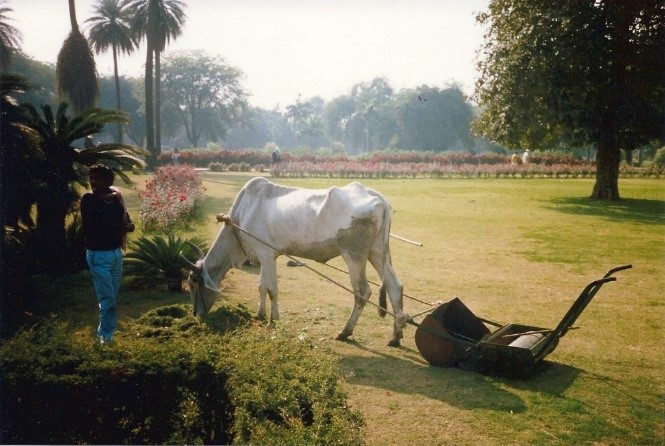

Yet Indians think differently about cows. Cows are given deference. That’s why I’ve seen bulls given charge of major intersections in Indian cities. Indian bovines are often given tasks that westerners give to horses: like mowing the lawn. It’s a switched hierarchy.

As for horses, westerners generally don’t eat those either—although they sometimes feed them to their dogs and cats in a form that can’t be recognized on the grocery store shelf. It’s okay as long as it’s under the radar. The dogs and cats don’t know the difference.

Jainism—another way of Indian thinking—respects all life, however low on the totem pole. The followers are vegetarians, practicing nonviolence toward all living things. I’ve heard they don’t even step on bugs.

Anyway, all that made me think about how arbitrarily we hold to certain morals on the subject of animal treatment.

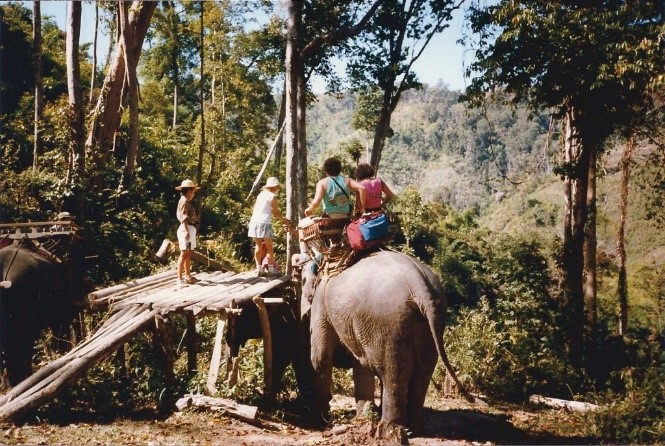

I rode an elephant in Northern Thailand many years ago. Parked upon its leathery back, the big lumbering beast carried me up a series of switchbacks and over steps into the forested hills. It was precarious and I pondered if the animal might step on me once our wooden saddle eventually loosened and slipped off the elephant’s back.

What happened astounded me. At the first big step up, the animal’s trunk came back—probingly—to touch the saddle, the straps, and then my knees and those of my co-passenger. Only after it was assured that its human load was secure did it proceed upward. That process occurred each time the elephant had to pull itself up and lunge forward. I was so impressed by its obvious concern for us that I ignored being coated with grassy green elephant snot when the caring, probing trunk inadvertently sneezed.

A few days later, back in “civilization,” I was looking to buy a new wallet in a Thai leather shop. I found one I liked, which had a small stamped image of an elephant on the inside. Curious, I asked the shop keeper if an elephant was killed to make the wallet.

“No!” the shop keeper sneered. Then he added, “Him already dead, mister.” For some reason I bought the wallet anyway—maybe just to remind myself about different perspectives, and about lines we draw in the sand.

At an “aquarium” in Eastern Australia my wife and I were invited to feed anchovies to a dolphin. It was after hours. I’m not a huge fan of these places, but the idea of getting close to a dolphin was enticing. Obviously the air-breathing, finned animal simply wanted the food we had in our hands, but there was something else. The animal came right up to us, head out of the water, and looked us over—eye-to-eye. It jumped and did tricks voluntarily. There was a strong presence. Yet those very animal are eaten by many seafaring nations; whales and pinnipeds too.

Examples of higher animal presence are so abundant, I could go on and on. And yet, each country has different customs concerning how different animals are respected and treated regardless of the animals’ specific higher qualities. It’s arbitrary. Our house pets might become a delectable Christmas dinner in China—if they had Christmas there.

So the way we treat animals really has less to do with logic than it does with drawing lines in the sand. It’s deciding that, since we are right and “they” are always wrong, our own way is correct over all the others. But viewed from different vantages, all these “customs” seem a bit off.

I’m getting bugged as I write this.

That’s why I’ve decided upon a new course of action: I’m not eating any more animals of a higher order. And if other cultures conclude that beef is taboo, then I’m not offending them by eating that either. I can’t live by arbitrary lines in the sand and I must respect all. No more insensitivity and mistreatment to fill my stomach.

I’ll just have to eat what’s already died: like roadkill. No harm there.

I imagine that could work for us: “Honey, pull over quick! I see dinner—in the ditch.”